Lax oversight, no-bid contracts and mysterious pricing: Inside the black box of COVID testing

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Testing was the key, everyone knew that. It was April 2020, and COVID-19 was spreading uncontrollably. Health officials in states across the country were desperate to expand their testing capacity. That was the only way to monitor the virus and possibly contain it.

If any state could succeed at this task, it was Minnesota. The state is home to some of the nation’s leading epidemiologists, and the Minnesota Department of Health is one of the best-regarded public health agencies in the country. Yet Minnesota, like other states, was floundering. The state needed to be conducting tens of thousands of tests every day but was administering only a few hundred. Worse, state labs were running dangerously low on testing supplies.

Minnesota Gov. Tim Walz challenged the state’s health officials to significantly ramp up COVID testing. The stakes were high. The pandemic had paralyzed the nation and had started killing hundreds of Americans each day. And Walz, less than 18 months into his first term as governor, was staking his political future on reassuring Minnesotans that his administration could guide them out of the crisis.

Walz characterized the state’s testing plan as “Minnesota’s moonshot.”

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

“Minnesota has tested about 40,000 since the beginning of this,” Walz said a month into the pandemic. “We need to be testing 40,000 a week or more.”

A year later, the moonshot seemed to have worked. By this April, Minnesota was administering nearly 200,000 tests per week, about five times Walz’s initial goal. The state has completed more than 10 million since the pandemic began. More than 562,000 COVID cases have been identified through testing, and Walz has used the data to intensify or roll back restrictions on schools and businesses. State health officials are using the information to spot and contain potential outbreaks as new variants emerge and rip through younger populations.

“Until we have the vast majority of the population vaccinated, testing is going to continue to be incredibly important,” said Christina Silcox, a health policy fellow at Duke University. “Because we see these variants coming up. We want to make sure that we understand not only who's infected but what they're infected with.”

Public health experts consider Minnesota’s testing program a success. But shooting for the moon wasn’t cheap.

An APM Reports investigation has found that the testing program in Minnesota — and in states around the country — relied on no-bid contracts for companies backed by private equity, regulatory shortcuts, and a complicated payment structure that will eventually pass tens of millions of dollars in testing costs on to the public through higher health insurance costs. The state-contracted lab that conducted surveillance testing on tens of thousands of Minnesota schoolchildren and parents who were asymptomatic hadn’t obtained federal authorization for such tests.

Over the past six months, APM Reports combed through thousands of pages of documents from Minnesota and other states, dozens of testing contracts and billing records, and interviewed testing experts about the problems with the system.

The records and interviews show that even Minnesota, a state internationally known for its public health system, was initially caught flat-footed by the pandemic. Many of the problems stemmed from the Trump administration’s decision to forgo a national testing strategy, leaving states to tackle the logistical challenges largely on their own.

“We were now thrust into competing not as a nation on the global scale, but competing as one state against another state,” Dan Huff, assistant commissioner of the Minnesota Department of Health, said in an interview.

When all of this is over, the whole system of how testing has occurred in this country and how it's basically been driven by companies needs to be reassessed.

- Susan Butler-Wu, USC

The tab for COVID-19 testing has so far totaled more than $130 million in Minnesota. Most of the money has been dedicated to paying for spit tests administered by New York-based Vault Health and its lab partner, IBX. The companies signed a no-bid, emergency contract with Minnesota last year. Vault had previously specialized in men’s health care, and IBX was a Rutgers University-affiliated lab that was spun off into a private company less than two months before it inked a deal with Minnesota. The companies’ expansion into COVID testing was backed financially by private equity.

In the sprint to expand testing, IBX never obtained authorization from the Food and Drug Administration to conduct tests for asymptomatic COVID cases, a regulatory shortcut that federal officials have chosen to encourage, the APM Reports investigation found. As a result, there’s no publicly available data on how accurate IBX’s spit tests are for patients without symptoms compared to those of other testing companies — even though IBX and Vault regularly tested tens of thousands of schoolchildren, parents and teachers across Minnesota.

In addition, as part of its contract with Vault and IBX, the state negotiated a complex billing arrangement that obscures the true costs from the public. The companies have been billing insurance companies far higher prices — as much as $530 per test — in an attempt to offset costs of testing people who don’t have or didn’t list insurance. Health economists say this approach will result in insurance companies eventually passing the costs of testing on to consumers.

Still, public health experts contend that the rush to increase testing was critical to combating the pandemic and saving lives, even if a few corners were cut in the process. It was an ends-justify-the-means approach that was largely successful. State officials, by partnering with Vault and IBX, have delivered on their promise to test Minnesotans on a massive scale with fast results.

But with the pandemic now more than a year old and with cases declining nationwide, some experts want a reassessment of how testing was scaled up. Seventeen months later, many critical details about COVID tests — the contracts, the tests’ effectiveness, who’s regulating them, how much they’re costing and who’s paying — remain murky and largely unknown.

“When all of this is over, the whole system of how testing has occurred in this country and how it's basically been driven by companies needs to be reassessed,” said Susan Butler-Wu, associate professor of clinical pathology at the University of Southern California’s Keck School of Medicine. “How many bajillions of dollars have gone into this?”

Vault’s insurance charges

Vault’s charges to insurance companies, the federal government, Medicare and other programs vary widely. The discrepancy between the amount of money Vault charged and eventually collected is most evident between publicly funded programs and private insurance. IBX has yet to supply billing information to the state of Minnesota.

Desperate for tests

True to their state’s sterling public health reputation, Minnesota officials got off to a good start addressing the pandemic. At a March 2020 news conference, just days before the state’s first confirmed case, Walz and his health administrators confidently announced that the state public health laboratory had the capability to test for COVID-19.

But their confidence soon evaporated.

On March 13, President Donald Trump declared COVID-19 a national emergency, which helped provide billions in federal funding to fight the spread of the disease.

On the same day as Trump’s declaration, Minnesota health officials were putting together a “shopping list” to acquire the materials to test 15,000 people. It was the first time they realized there were worldwide supply shortages.

“Right now, I don’t know what is limiting supply,” Huff wrote in an email. “The issue seems to be that we get an order of one thing and then run out of the next thing on our list.”

Huff’s email messages were among thousands of records obtained by APM Reports through a public records request related to the state’s testing program. The records range from early March through April 2020, a critical time when health officials were trying to understand the virus and desperate to increase testing capacity.

The initial strategy under the Trump administration relied on states to handle testing logistics. Public health labs, which were shortchanged for years, were now being asked to increase testing capacity with scarce resources during a raging pandemic. This approach created a patchwork system that makes it difficult for the public to understand the relationships between states and testing companies and the total cost of testing.

The initial strategy under the Trump administration relied on states to handle testing logistics. Public health labs, which were shortchanged for years, were now being asked to increase testing capacity with scarce resources during a raging pandemic. This approach created a patchwork system that makes it difficult for the public to understand the relationships between states and testing companies and the total cost of testing.

The logistics of mass testing are complex. COVID tests involve two steps: collecting a sample, for instance with a nasal swab or saliva cup, and submitting that sample to a lab for analysis. Mass testing requires not just smooth organization to ensure samples aren’t lost or mislabeled, but also a huge amount of supplies. Quick turnaround times were also necessary to curtail a highly contagious virus that was spreading quickly across the globe.

In many instances, states were given little to no help from the Trump administration. And some of the assistance the feds did provide in the early weeks of the pandemic bordered on the ridiculous. A White House official fervently announced in an email to the governor’s office that the federal government was shipping testing equipment to the state public health lab to help boost testing capacity.

“You do not need additional reagent or any other items to run these tests,” wrote Zach Swint, with the White House Office of Intergovernmental Affairs.

It turned out to be a hollow promise. The 15 machines arrived with only five test kits, enough to do just 120 tests.

“This is so unbelievable,” Huff wrote. “What twisted world did we end up in where this happens?”

By early April, state health officials realized the federal government would offer little assistance. They were forced to ration: Only health providers, first responders and hospitalized patients would be tested. It was extraordinary that a state health department, celebrated for its ability to spot and contain disease outbreaks, should have to triage testing supplies in the face of a rapidly spreading deadly virus. But there was no choice.

“We shouldn’t be testing everything,” Myra Kunas, assistant medical director with the Minnesota Public Health Lab, wrote in March. “This is why we’re out of supplies this early.”

With the state desperate for supplies, well-connected lobbyists and business leaders were quick to offer their services.

Kurt Zellers, a former state representative who served as speaker of the Minnesota House from 2011 to 2013, emailed Walz’s chief of staff, Chris Schmitter, to offer 1 million tests a week through an unnamed South Korean company. Schmitter appointed an aide to look into it. The company eventually provided testing supplies to Hennepin Healthcare, according to the Minnesota Department of Health.

The international management consulting firm McKinsey & Co. pitched four weeks of pro bono services for overall strategy consulting and analytical support. Schmitter called it a fantastic offer.

At the recommendation of a friend, the CEO of North Memorial Health pitched a testing platform at a cost of $20 per test for the first 100,000 tests. He said the distributor had the option of delivering 2 million tests over the following weeks — and Minnesota officials needed to act fast. “Timing is becoming critical as he is selling to Idaho and other states as we speak,” wrote the CEO, Dr. J. Kevin Croston.

By the end of April, Trump announced that there would be no federal strategy on testing. Instead, he directed states to “develop testing plans and rapid response programs,” “maximize the use of all available testing platforms and venues,” and “identify and overcome barriers to efficient testing.”

By that time, Minnesota was already relying on the Mayo Clinic. The Rochester, Minn.-based health system is one of the largest hospital reference labs in the country and was offering to set aside 20,000 tests a week for Minnesota residents.

Mayo’s offer was a mix of generosity, tactful lobbying and necessity. Behind the scenes, Mayo and the University of Minnesota were both pitching a testing contract to the state. Mayo was also trying to keep up its lab capacity at a time of scarce resources, according to the emails.

Any cutback of Mayo’s testing capacity could mean the federal government and testing supply companies might reallocate supplies to commercial labs like Quest Diagnostics and LabCorp. So state officials were encouraging Minnesota hospitals to send tests to Mayo.

“This is why Mayo is trying to keep up the volume. If the reagents drop, the Feds send reagents elsewhere,” Huff wrote.

In addition to relying on public health labs, hospitals and other commercial labs across Minnesota, the state eventually partnered with Mayo and the University of Minnesota on a statewide testing program. The contract, announced in late April 2020, required 20,000 daily diagnostic tests, which help identify positive COVID cases, and 15,000 antibody tests, which help detect whether a person has been exposed to the virus.

“We are smothering this issue of testing, I’d argue, with talent, better than any place on the planet,” Walz said at the time.

The state delivered at least $35 million to the University of Minnesota and Mayo for testing, according to budget records.

The contract was a good start, but it still fell short of what the state needed. There were reports of supply shortages again in July, and Minnesota officials began looking elsewhere for more tests.

A little spit goes a long way

As Walz was preparing to launch his moonshot in April 2020, a New Jersey-based lab was busy gaining authorization for an innovative new COVID test that didn’t require intrusive nasal swabs. On April 10, 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved the nation’s first saliva test for COVID, developed by RUCDR Infinite Biologics at Rutgers University. A few months later, the laboratory would spin off from the university and change its name to IBX.

After gaining emergency authorization from the FDA for its spit tests, IBX quickly partnered with Vault Health to market, manage and sell its program. The two companies had a prior relationship because IBX conducted fertility tests for Vault’s customers.

The companies would partner on a much larger scale with COVID testing. IBX served as the lab to conduct the testing but needed help finding health care providers to order, manage and process the samples. Vault had the telehealth services and was in survival mode after COVID shut down the nation — and curtailed its men’s health business.

A cash infusion from private equity helped position both companies for the work. Prior to the pandemic, Vault had secured $30 million from private equity firms founded by billionaires David Rubenstein and Chase Coleman III. In June, Rutgers sold the lab now known as IBX for $44.4 million; the hedge fund Viking Global Investors is the majority investor.

With that financial backing from Wall Street, IBX and Vault prioritized COVID-19 testing in their updated business plans. They realized that businesses and governments would have an urgent need for frequent tests that could be turned around quickly. But there was an initial problem — low demand. Few orders arrived during the first month of work because most people were busy quarantining, Vault CEO Jason Feldman said.

“And then the PGA [Professional Golfers Association] called us and said, ‘We want to get golfers back on the golf course. Can you help us?’ And that was the start,” Feldman told the “Habits & Hustle with Jennifer Cohen” podcast in February. “Once the golfers did it, then the NBA wanted to do it. And sports came back and colleges came back and businesses came back.”

Those relationships, along with deals with JetBlue and Bristol Myers Squibb, allowed Vault and IBX to market the tests to colleges and to state and local governments.

Suddenly business was booming. Some of the nation’s largest colleges and universities, including Penn State University, the University of Oklahoma, the Georgia University System and Ohio State University, signed testing contracts with Vault and IBX. Eleven states and several cities and counties also entered agreements. A review of 25 public contracts and state and federal spending reports shows Vault and IBX have earned or have agreements to earn at least $270 million.

Top 10 public payers

This is a list of government entities that have paid the most money to Vault and IBX. The list is based on a review of contracts, and state and federal websites that outline government spending to vendors. We used the higher dollar amount whenever the figures listed in the contract differed from the government spending site.

The two companies became among the largest COVID-19 testing providers in the country. That success was due in part to the companies’ ability to meet urgent testing demand from states. West Virginia filed an emergency request for 10,000 tests with Vault in late August, according to email records from the state. The total cost, including an expedited charge, was $856,626. Wyoming entered into an agreement without receiving a formal written proposal because the state needed to get a contract in place quickly, said an official with the Wyoming Department of Health.

Testing demand in states like Wyoming, West Virginia and Minnesota meant a solid return for the key investors in Vault and IBX. The companies were also getting funding from the federal government, which paid for testing for those without insurance. A review of records shows IBX received $36.4 million for testing and treatment from the U.S. Health Resources and Services Administration through July 15. Vault received $9.5 million. Of the more than 9,000 providers that received federal reimbursement for COVID-19 testing, IBX ranked 17th, according to data released this month. Vault is in the top 75.

It’s hard to determine the overall revenues of the two companies because both are privately held, but Vault’s Feldman said in a February podcast that “in October, our business is now a few hundred million dollars…”

The bulk of those revenues came from Minnesota, which became one of Vault and IBX’s biggest customers.

Unlimited testing

The partnership among Minnesota, Vault and IBX began modestly in early August with a deal worth a mere $6 million. The initial goal was to provide at-home tests to educators, staff and child care providers before the start of the school year. The early program received a lukewarm response, but it served as a trial run for what would become a massive testing effort.

They needed testing capacity, and we were able to respond with testing capacity at a scale that nobody else was able to do.

- Christopher Goldsmith, Vault

To date, the state has committed about $100 million to Vault and IBX. Under an updated contract signed in April, Minnesota increased its testing deal with the two companies to $75 million. The state has also committed nearly $25 million under a bulk purchasing agreement.

Minnesota could ramp up the contract because of the public health emergency, which allowed officials to bypass the normal bidding process. Minnesota spent $4.7 million in state funds to help IBX build a lab in Oakdale that opened in October. The deal allows IBX to keep the equipment after the pandemic ends.

While the terms were generous, the impact was critical: The IBX lab helped Minnesota more than double its testing capacity. Jan Malcolm, commissioner of the Minnesota Department of Health, also said the testing services allowed the state to ramp up testing on asymptomatic patients.

Throughout the fall, Minnesotans came to increasingly rely on Vault and IBX’s spit tests. The test appealed to state health officials because it’s considered less invasive than a nasal swab. It also reduced the need for swabs, a scarce resource in the early days of the pandemic. Between early September and the end of 2020, the state’s testing expanded by 75 percent.

“They needed testing capacity,” Vault Chief Operating Officer Chris Goldsmith told APM Reports, “and we were able to respond with testing capacity at a scale that nobody else was able to do.”

By January, Minnesota officials were preparing to reopen elementary schools across the state. A key piece of the reopening plan was for the Health Department to encourage parents, students and teachers to take COVID tests at least once every two weeks, regardless of whether they had symptoms. The Health Department website and school districts referred students and teachers to Vault’s spit tests. The spike in testing through the fall and winter is a clear indication that many families followed that guidance.

The two companies have processed more than 1.7 million tests for the state of Minnesota through this month, Goldsmith said.

Roughly 70 percent of those spit tests taken through March were completed at community sites run by Vault or the Minnesota National Guard, according to Health Department data.

The community sites are managed by relatively few staff members. An employee checks you in, hands you a spit tube packet and directs you to a folding table that has been sanitized by another worker.

Once there, the test taker uses a phone or supplied tablet to access a website that requires you to enter personal information, including age and insurance coverage if you have it. The website also asks whether you are showing any symptoms of COVID-19.

The state contract required IBX and Vault to return test results within 48 hours, but in many instances results were delivered in less than a day.

The test is the same regardless of symptoms. You spit into the tube until you’ve produced the necessary amount of saliva, which goes to a laboratory where an analysis checks for the presence of the SARS-CoV-2 nucleic acid. But researchers say testing people without symptoms is much trickier. The larger pool of test takers typically means a higher error rate.

This approach — testing a huge number of people regardless of symptoms — is called surveillance testing. One of the most challenging aspects of COVID-19, public health experts say, is that people who don’t have symptoms, and who may not even know they’re sick, can spread the virus. Surveillance testing can catch these so-called asymptomatic cases before they spread. With vaccines still in short supply early in 2021, Minnesota officials argued that surveillance testing was key to limiting spread of the virus.

By early 2021, Walz was hailing the state’s surveillance testing program as “nation-leading.” At a February event at Parkview Center School in the Twin Cities suburb of Roseville, Walz said testing was vital to loosening restrictions in schools, businesses and elsewhere.

“[Testing] is probably now more important than it's ever been,” he said. “So we're pushing the case and our capacity to continue to expand this. Pretty much unlimited.”

Successful surveillance testing required a huge number of tests that are efficiently administered and analyzed. Vault and IBX accomplished this on a massive scale.

But there was one significant flaw in this system. Effective surveillance testing requires that tests accurately detect asymptomatic cases.

And Vault and IBX’s spit tests were never authorized for asymptomatic testing by the FDA.

The feds give a pass

To gain FDA authorization, a company first has to test its test. A company must submit data showing that the test can effectively detect the disease in patients with symptoms and in patients without symptoms. The FDA typically requires companies to test both symptomatic and asymptomatic populations and report error rates before they receive federal approval to market a test.

The risk is that an inaccurate test can result in false positives (a person wrongly believing they have the virus) or false negatives (a person wrongly believing they’re free of the virus). Both errors can endanger lives.

Yet the FDA relaxed its standards during the pandemic, the APM Reports investigation found. FDA officials told testing companies that they could administer their tests to people without symptoms despite not having the emergency use authorization for such tests. That means IBX and other companies without authorization never had to demonstrate to federal regulators that their spit tests reliably detected COVID in people who were asymptomatic.

“We're encouraging it because we only have a small number of tests right now that are authorized for asymptomatic screening,” Timothy Stenzel, director of the office of In Vitro Diagnostics and Radiological Health at the FDA, said on a December conference call.

Some companies did seek and receive FDA authorization to test asymptomatic people, according to the FDA’s website.

The IBX test produced sterling results compared to the effectiveness of nasal swabs on patients with symptoms, according to its emergency use authorization. But the FDA document, updated May 27, says “testing of saliva specimens is limited to patients with symptoms of COVID-19.” The emergency authorization allowed health providers to prescribe tests whenever they were deemed necessary. Yet IBX and Vault have marketed their tests to at least one public entity for surveillance testing without FDA authorization for that purpose.

The FDA’s Stenzel cautioned in December that the FDA doesn’t know the performance of these tests on asymptomatic patients. He’s urged testing companies to supply the FDA with additional data.

IBX hasn’t applied to the FDA for its test to be specifically used on asymptomatic people, according to Russ Hager, executive vice president of IBX. He said his company processes tests prescribed by health care providers like Vault.

“Healthcare providers, operating under their own practice of medicine authority, may decide to prescribe use of a test authorized for symptomatic patients only on a patient that is asymptomatic,” Hager said in a written statement. “We process all tests that are prescribed by healthcare providers.”

To complicate matters, there were major disagreements within the Trump administration that created confusion over the FDA’s oversight of lab-developed tests.

Goldsmith, with Vault, said the federal government’s shifting standards made it difficult to follow appropriate guidance. He said the urgency of the pandemic prompted his company to provide tests to a wide variety of patients.

“There's different interpretations of what was clinically significant for justifying a test or not,” he said. “Given what was happening, we said, ‘Yeah, those tests needed to be provided.’”

The public still doesn’t know how effectively the spit tests detect COVID in patients without symptoms — even though thousands of Minnesota parents and teachers were relying on the test results during the winter and spring COVID surges.

When the state publicly announced its partnership with Vault in August, health officials said they reviewed the testing data and concluded the test “can be used with confidence.” The state didn’t provide any specific data to back up those claims at the time.

And despite IBX saying the company doesn’t track false positives and negatives among patients without symptoms, Sara Vetter, assistant division director for the Minnesota Public Health Laboratory, said in an interview that IBX did submit data outlining asymptomatic results to her department. She said the information was from a Rutgers University analysis of 1,000 people that were tested every two weeks with both nasal swabs and saliva. The unpublished study found that saliva tests may be more sensitive than swabs for detecting COVID-19, according to information that IBX supplied to the state.

“It was matching as close to their original symptomatic patients that they tested,” she said. “With all of that information, we felt comfortable proceeding with this test.”

Hager, with IBX, said the overall complaint rate to the company “concerning allegations of false positives/negatives is less than 0.001%.”

Still, officials who monitor FDA’s regulations said testing companies were unlikely to show urgency about obtaining authorization to test people without symptoms if the federal government didn’t demand it.

“When the FDA says to you that we're going to look the other way, when you promote in an off-label way, there's no incentive for the company to come back with additional data and expand the indication,” said Peter Lurie, a former FDA official who now runs the Center for Science in the Public Interest, a consumer advocacy group.

Lurie said there are higher error rates when testing for patients without symptoms. And he said the FDA’s decision to allow companies to engage in so-called off-label use is walking a fine line.

“When you move from testing a population in which the infection is relatively high, such as one with symptoms, to a population that is relatively low, such as those who do not have symptoms, the likelihood that your positive test is really a positive test can plummet,” Lurie said.

FDA officials declined an interview request and wouldn’t say whether it’s reviewing any amendments to IBX’s authorization. An agency spokesperson pointed out that the FDA had authorized certain tests for asymptomatic patients. The first authorization was issued in July 2020.

Some testing experts agree with the FDA’s strategy, saying it’s better to test as many people as possible. “Every positive you catch is actually kind of a bonus,” said Christina Silcox with Duke University. “If you missed one particular positive one week, but you're able to catch it three days later, or seven days later, then you've still been able to catch an extra one that you wouldn't have otherwise caught.”

But there is a downside. An error in tests could lead to future outbreaks if an infected person continues to wrongly think they don’t have COVID. In January, the FDA issued a safety communication warning of a risk of false results with a commercial test developed and sold by the California-based company Curative. The FDA urged the public to use the test only “in accordance with its authorization.” While some communities stopped using the tests, others continued to do so. Officials with Curative say they stand by the test.

Officials with Minnesota’s Health Department said they regularly monitored test results from IBX and other labs. There were a small number of false positives and negatives related to IBX’s test.

“We're talking about one to two a month, out of the tens of thousands of tests that were happening,” Vetter said.

There have been mistakes with Vault-administered tests in other parts of the country. In October, there were five instances of false positives among students at Vanderbilt University. The university said that the problem was a clerical error and that the students who received false positive results could leave quarantine. Vault’s Goldsmith said the problem wasn’t with the testing system but with how the results were processed and reported.

The university announced in January that it was ending its relationship with Vault and began using a different testing provider. The university didn’t respond to repeated questions about the contract. Vault’s Goldsmith said he believes the university was looking for a lower-cost solution than what Vault could provide.

Vault and IBX have also pitched their spit test for use among people with no symptoms to at least one university system, even though they didn’t have FDA authorization for that use. APM Reports reviewed contracts and bid proposals for more than 20 entities, including seven public colleges and universities. (The review didn’t include Vanderbilt, a private university exempt from public records laws.) A testing proposal to the University System of Georgia shows the companies willing to “test asymptomatic students, faculty and staff at a rate of approximately x% of students per day.” Officials with Ohio University also actively encouraged students and faculty to get tested through Vault regardless of symptoms.

The marketing efforts by Vault and IBX have worried some testing experts who say labs should be careful to not market their tests beyond what has been authorized by the FDA.

“If you're marketing a test for asymptomatic use, you need to have examined its performance in that population for that intended use,” said Butler-Wu, with USC’s School of Medicine. She said she’s surprised the FDA hasn’t taken direct action on testing companies that are openly marketing to asymptomatic patients if they don’t have the authorization.

Alan Wells, a professor of pathology and laboratory medicine with the University of Pittsburgh, said IBX could have submitted additional data on its test’s performance with asymptomatic patients. “I'm a little perplexed by that, personally,” he said, “because it's not that difficult to upgrade your [authorization] to get asymptomatic testing.”

The bid proposal Vault and IBX submitted to the state of Minnesota does not include language related to asymptomatic testing. Still, health officials say it was critical to their public health strategy.

“The whole strategy here was to make testing broadly available with as fast a turnaround time as we could get, particularly because of the high degree of asymptomatic spread of this disease,” Malcolm said last week. “Making that testing as accessible as possible was just a very, very key mitigation strategy.”

Goldsmith said IBX’s test was “one of the best out there” based on the thousands of customers who hired the companies for testing.

But there’s no publicly available data — from the companies, FDA or states — on how effectively the tests can detect COVID-19 in people without symptoms. And those who work in the regulatory field are trying to determine FDA’s next move.

“It's just really messy right now,” Patricia Zettler, an associate professor at The Ohio State University College of Law and former attorney with the FDA, said earlier this year. “FDA has been criticized on both sides throughout the pandemic, as an obstacle to faster testing early in the pandemic. And now questions are being raised about whether the testing we have is actually good enough.”

Vetter, with the Minnesota Department of Health, said she would welcome clear guidance from the FDA that creates consistency across manufacturers.

Testing companies operating under an emergency use authorization will also have to decide whether they want to seek non-emergency FDA approval, a much more arduous process, after the federal health emergency is lifted. IBX’s Hager wouldn’t commit to taking that step.

“We suspect that at some point in the future, FDA will no longer find the emergency circumstances to exist and thus, we will need to consider the submission of a permanent marketing application to FDA,” he said.

True costs remain hidden

The biggest mystery over Minnesota’s testing program is how much it will cost.

In its contract, the state of Minnesota promised to pay Vault and IBX between $87 and $121 per test. The cost varies depending on whether the test is administered at a community site managed by state officials, a site managed by Vault or at the person’s home, requiring overnight delivery. Minnesota’s price structure is similar to what Vault and IBX are charging other states, colleges and universities. The test costs are also consistent with what other top testing providers like Quest, LabCorp and CVS are charging. However, the Mayo Clinic and the University of Minnesota charged less — $62 a test — in their first contract with the state.

Minnesota’s contract requires Vault to collect health insurance information from patients and to bill private insurance before seeking funds from the federal government or states.

The insurance requirement is significant because nearly 75 percent of Minnesotans taking tests through Vault have reported their insurance information, according to state data. That means for three-quarters of tests, Vault was required to bill private insurance companies first.

How much is Vault collecting from insurance companies? That’s where things get complicated.

APM Reports reviewed insurance billing records provided to the state by Vault and individual billing statements sent from insurance companies to patients. Vault and IBX frequently billed insurers substantially more than the state rate and, in some instances, up to five times more than the state’s contracted prices.

A review of health insurance billing statements sent to patients shows Vault and IBX were charging an average of $522 a test, significantly more than the top state rate of $122.

Vault billed insurers $113.3 million for 743,419 tests between November and March, according to state data. That’s an average testing cost of $152 for Vault’s services alone.

Minnesota contract vs. insurance charges for one test at a state-managed collection site

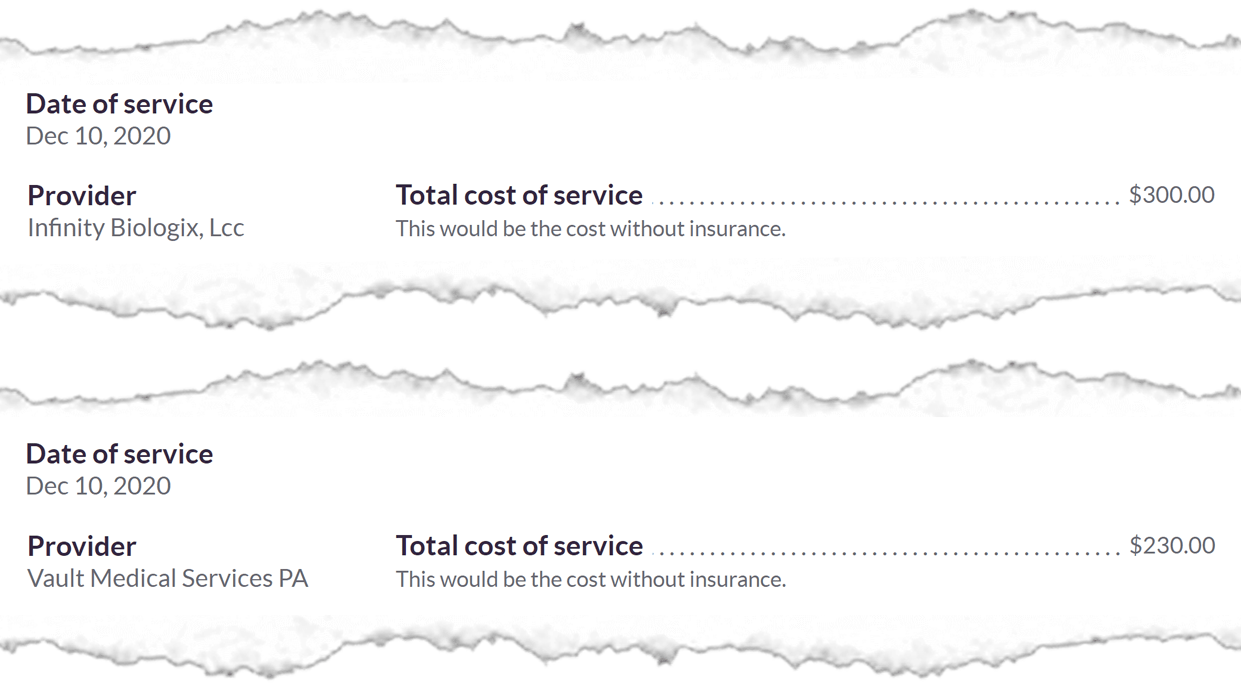

The Health Department says IBX has not supplied any billing data to the state yet. Individual bills examined by APM Reports show IBX has consistently charged health insurers $300 a test.

Medical providers frequently bill insurance companies higher rates, with the expectation that insurers will negotiate a lower final payment, Vault’s Goldsmith said.

In all but one instance, insurance companies have struck a deal with Vault and IBX. For example, HealthPartners is now paying Vault and IBX set rates between $150 and $214 for testing services. That’s roughly half what the companies had billed the insurance firm, but it’s still higher than the state-negotiated rate.

One reason for those rates is that health insurers have far less negotiating power for COVID testing. The federal government is requiring health insurers to cover the full price of COVID-19 testing without passing any costs on to consumers. That means insurers have little leverage with testing companies. A national trade group has complained about high testing costs, which it has characterized in some instances as “price gouging.”

“We urge Congress to examine how some diagnostic testing providers are charging exorbitant amounts taking advantage of the requirement that health insurance providers pay the cash price, regardless of the reasonableness of that price,” America’s Health Insurance Plans said in a written statement in May.

IBX and Vault appeared to be charging insurers higher rates than government rates. For example, Medicare was paying Vault $37 per claim, well below what private insurers were paying, according to billing records from the state.

George Nation, who has studied medical billing as a professor of law and business at Lehigh University in Bethlehem, Pa., is more blunt. “I wouldn’t be surprised if profit motive is playing an outsized role here. When you see an opportunity to charge a higher price than may be reasonable, providers tend to take it,” he said.

When APM Reports questioned Goldsmith about the company’s billing practices, he said that any insurance payment above the state’s set rate won’t be company profits. Instead, he said, Vault would use any excess to defray the costs of testing people without health insurance or to make up any payments from the government or other providers that aren’t as high as the state rate.

The contract Vault signed with the state designed this complex funding formula. Here’s how it’s supposed to work: The state pays Vault for the costs of testing people without insurance. Vault then bills insurance companies for the tests of those who are covered. If the company recoups any amount higher than the state’s set rate from insurers, Vault is supposed to hand that excess money back to Minnesota, according to the contract, to offset the costs to taxpayers for testing the uninsured.

Essentially, it’s a way to leverage insurance payments to cover the costs of tests for everyone, even those without insurance.

“This is a way for Minnesotans’ dollars to go further in that we can do more tests than we would be if Minnesota just had to pay for every single test,” Goldsmith said. He added that Vault and IBX already factored a profit for each test when they negotiated a contract with the state. And he expects the state to end up owing his company for services despite the higher insurance charges.

Insurers expressed concerns about the payment structure. The trade group representing many of Minnesota’s health insurance providers is proceeding carefully in complaining about testing costs. However, it says it was surprised the state required Vault and IBX to seek health insurance reimbursement for testing.

“Vault and IBX are new vendors in Minnesota operating under an exclusive agreement with the State that did not fully take into account how or how much Minnesotans with insurance would be charged for their services,” Lucas Nesse, president of the Minnesota Council of Health Plans, said in a written statement.

But several insurance executives have been privately questioning the billing process to the state, according to records obtained through the Minnesota Department of Commerce, which regulates the insurance industry.

“Vault's site publicly displays $119,” Nancy Molenda, government relations associate director at UCare, wrote to the Minnesota Department of Commerce in December. “Therefore, our intent is to pay Vault $119 and that would be considered payment in full, including when billed amounts greater than $119. FYI — we have received claims up to $275 from Vault.”

Officials with UCare, HealthPartners, Medica and UnitedHealth Group all declined comment when asked about Minnesota’s testing program.

Complaints about Vault and IBX’s testing costs prompted a review of the program by the Minnesota Office of the Legislative Auditor.

Last week, the government watchdog released a report saying the state did not overpay for testing for those on the state employee health insurance plan and on state-subsidized insurance like Medicaid and MinnesotaCare. But the report found that the initial testing charges were lowered only after the health insurance industry raised concerns about the costs. The review was done in the early stages of the billing process.

“The bills are still coming in,” said Joel Alter, director of special reviews with the Office of the Legislative Auditor. “So the health plans and state officials need to continue to review the claims they receive very carefully.”

Alter also stressed that the review studied only a small slice of those tested in Minnesota — those on publicly funded insurance — and did not include a review of private insurance costs, which is the data APM Reports reviewed. During a recent legislative hearing, Alter said “we also have to wonder, when those private insurance companies got a bill from Vault or IBX, did they pay it in full?”

A similar insurance requirement was also included in Minnesota’s contract with the Mayo Clinic and the University of Minnesota, said Margaret Kelly, deputy commissioner of the Minnesota Department of Health. The difference is that the two Minnesota health providers had existing contracts with Minnesota’s insurance companies, while Vault and IBX did not. All of Minnesota’s insurers now have contracts with Vault that should lower the overall price of testing, Kelly said.

Health officials also said they have no authority to dictate what private health plans and providers pay for testing. Instead, they said, their responsibility is to protect Minnesota’s treasury.

“Because of our fiduciary responsibility to taxpayers, if someone is covered by insurance, their insurance needs to pay for that,” said Assistant Commissioner Huff.

The contract was approved during an emergency, so the state wasn’t required to solicit bids from multiple testing companies. The measure also didn’t need approval by the Legislature. Without those guardrails, the Walz administration in effect created a hidden fee on private insurance to bankroll the testing program.

Though the precise costs of testing may be difficult to discern, there’s little doubt who eventually will pay the bill. Those costs will likely trickle down to consumers in the form of higher health insurance premiums, health billing experts say.

“The patients, ultimately, may not get the bill today, but they’re going to be the ones footing the bill,” Nation said.

States go their own way

Much of the haziness and lack of clarity about testing stem from the Trump administration’s decisions in the early months of the pandemic. The absence of a federal testing strategy and a severe shortage of supplies set off a free-for-all in which states and localities were left to solve a testing dilemma that plagued the globe. States, counties, cities, businesses and higher education institutions were all forced to come up with testing strategies to meet their own needs.

While Minnesota’s relationship with Vault and IBX is the most extensive, 10 other states have signed contracts with the companies for testing and vaccine distribution.

Delaware, South Dakota and Wyoming are paying the companies on a per test basis. Wisconsin is using Vault for at-home testing. Michigan used the tests at skilled nursing facilities on the state’s Upper Peninsula. New Mexico signed a contract with Vault but also works with Curative.

Some jurisdictions have also scaled back their partnerships with Vault and IBX. West Virginia, which still relies on Vault for community testing, canceled its at-home testing partnership with the company a week after it was announced in early December. State officials said they had concerns over cost and the time it took to get results.

Morris County, N.J, also canceled its at-home testing program. County officials worried that they would be required to pay for at-home testing kits that were requested but never used, said Scott DiGiralomo, director of the county’s Department of Law and Public Safety.

In Minnesota, 280,000 at-home tests were ordered but haven’t yet been returned, according to state records from March. Minnesota officials say the costs of those outstanding tests will be waived, but the contract says the sides will negotiate a settlement agreement for any unused test codes.

And in a signal that the rate of COVID-19 cases has declined in Minnesota, the state announced in late June that it was closing three of Vault’s community testing sites in the Twin Cities.

There are also a greater number of testing options than in the early months of the pandemic: 396 tests and sample collection devices have received emergency use authorization from the FDA. As testing options expanded, Vault has looked to provide other services to the public. It signed contracts with Minnesota and other states to manage COVID-19 vaccine sites. The company is also looking to provide mental health services in the future, Goldsmith said.

Vault and IBX would like to renew their testing contract with Minnesota, Goldsmith said. The contract allows for a three-year extension if needed.

The state, however, is considering all options. It is now seeking another contract that provides testing to schoolchildren who are too young to be vaccinated. Now that the state’s public health emergency has been lifted, the contract proposal is going through the traditional bidding process, Huff said.

“We have now the luxury that there's a lot of people offering good service of lab tests of saliva,” he said. “Back in the fall, Vault and IBX were the only ones on the market. We have a lot more options, and we're going to explore those options to see who can provide the best service and the best price.”

Huff said it’s possible Vault and IBX could win the new contract because the companies already have a partnership with the state and experience delivering testing services to Minnesota’s schools.

Vault’s relationship with Minnesota and other states is just one of many agreements signed between public entities and testing companies.

Those different testing approaches and costs obscure from the public the details of how the millions of COVID tests across the country were handled. Experts say the total price tag could take years to decipher.

A lot of money changed hands — or will change hands — and it’s not clear where it’s all gone, said Gigi Gronvall, senior associate at the Johns Hopkins Center for Health Security and developer of the COVID-19 testing toolkit.

“There are definitely a lot of players and not a whole lot of visibility,” she said.

Kori Suzuki and José Martinez contributed to this report.

Correction (July 21, 2021): This story previously stated that Vault received $30 million in financing from private equity firms managed by David Rubenstein and Chase Coleman III. In fact, Rubenstein founded a firm that invested in Vault, but he doesn't manage it. We regret the error.