Analysis: What's to blame for Minnesota's slow vaccination pace?

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

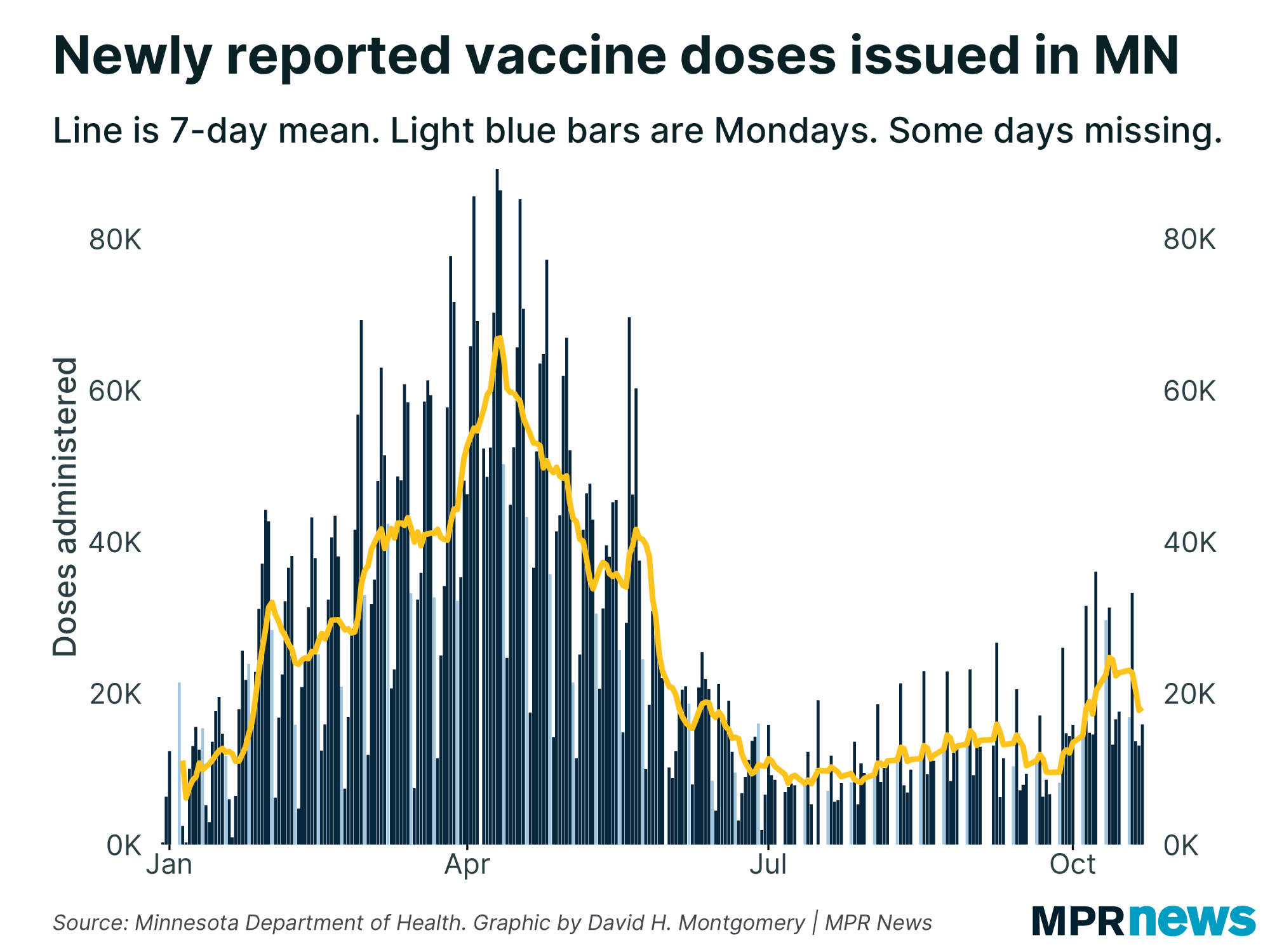

Minnesota is now on its eighth straight day of downward-trending vaccination rates.

Now, some of that decline is probably due to the fact that Minnesota's heartening spike in vaccinations the last week of January was unsustainable. It looks like vaccinations are trending down when in fact they might just be returning to normal after a one-time surge.

Of course, that's not an especially heartening explanation. We want to see the pace of vaccinations steadily increase. The fact that we're not returning to the dark days of 10,000 shots per day is good, but we could be doing so much better.

So why aren't we?

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

There are, in general, three big categories of explanations for why vaccinations could be low:

A too small supply of vaccines

Bad distribution of the vaccine supply

Low demand for vaccines

I won't be able to precisely quantify how much each of those three is to blame, but we can take a quantitative look at all three of those, which I'll do in reverse order.

Possible cause: Low demand for vaccines

First, we've got national poll numbers about so-called "vaccine hesitancy." A Kaiser Family Foundation survey in January found that around 6 percent had already gotten a COVID-19 vaccine, and another 41 percent of people said they'd get it as soon as possible. That 47 percent total is a sizable increase over December, when just 34 percent said they wanted to get a shot as soon as possible.

Meanwhile, around 13 percent of respondents said they definitely didn't want to get the vaccine, not much changed from December — the big change was people who had said they wanted to "wait and see" now becoming more comfortable with the vaccine.

And while some people in every demographic had their doubts, the share of people saying they wanted to wait and see was lowest among seniors — 21 percent — than any demographic group, while health care workers — 28 percent — were also less likely than the national average to want to wait; another 9 percent of health care workers said they didn't want to get it all.

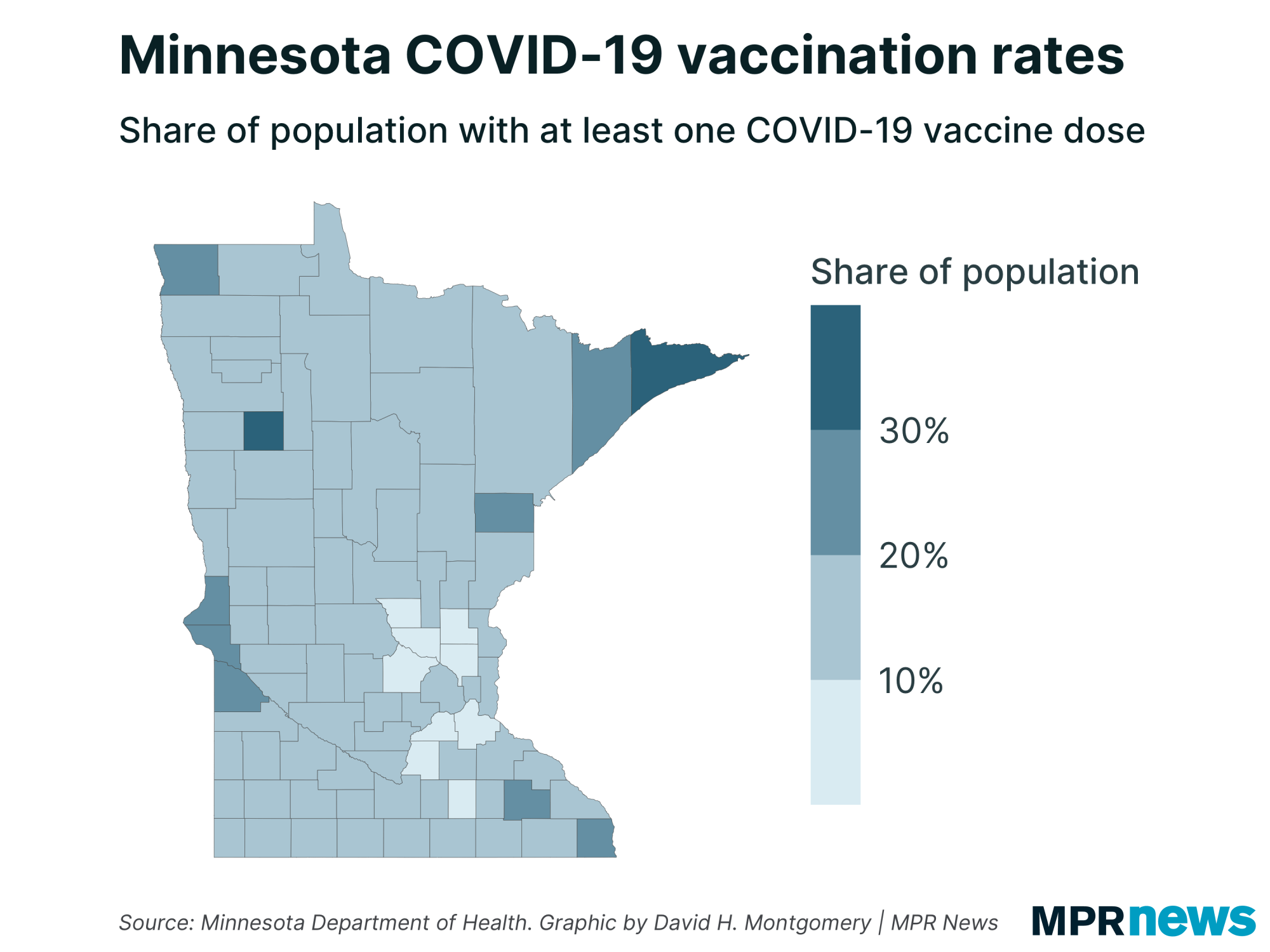

That poll isn't broken out by state, but there are a few things in the metrics we do have that could shed some light on vaccine hesitancy in a quantifiable way. For example, the survey found rural residents were among the least likely to want a vaccine as soon as possible. So far, most rural parts of Minnesota have the highest vaccination rates, while the Twin Cities metro area has among the lowest.

Now, this doesn't say too much, since rural Minnesota is also disproportionately elderly, and seniors are the most likely group to want a vaccine, for the obvious reason that they're among the most vulnerable to the disease. Still, if this map had showed Hennepin and Ramsey counties with the highest vaccination rates and rural Minnesota with the lowest, that might have been a sign that vaccine hesitancy was a driving factor here. But we see the opposite.

Possible cause: Bad distribution of the vaccine supply

The other key metric here is the number of shots Minnesota has on hand but isn't administering. This is a metric that could also speak to the second potential explanation: bungled distribution and administration of the vaccines by the state and health care providers. If either of these explanations are the biggest factor, we should see a huge number of unadministered shots sitting in freezers because the state and providers can't get them into people's arms.

Overall, Minnesota has received around 975,000 vaccine doses as of Tuesday, and has administered about 732,000 doses. That would imply 243,000 doses sitting in freezers, or around 25 percent of the total doses received. And indeed, the data from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention shows Minnesota has administered around 76 percent of its received doses — above-average, but about 20 percentage points behind the national leader, Utah.

So are there really 243,000 doses sitting around not being used? In a technical sense, that's the number of not-yet-administered doses, but a fuller look at the data shows these doses are mostly going into arms soon after arriving.

To understand this, we can use the state's data on the share of doses that get administered within three days after being received. Minnesota's goal is for all providers to administer at least 90 percent of their doses within three days (and 100 percent within seven days), and providers that don't meet this goal are subject to having their vaccine allotment reduced.

Overall, Minnesota is currently distributing 87 percent of its vaccine doses within that three-day period. Under the radar, this ranges from providers like Mayo Clinic and the state's own facilities achieving 100 percent distribution, to some providers vaccinating long-term care facilities at less than 50 percent of doses within three days.

Two weeks ago, Minnesota was averaging less than 70 percent of doses administered within three days; this rate has steadily been trending upward.

As a result of this, we can plot out the absolute number of doses that aren't being administered within three days of receipt. These numbers are sizable, but they're an order of magnitude smaller than the 243,000 gap between doses received and administered.

While at one time recently Minnesota had more than 75,000 doses that had been sitting around for more than 72 hours, that's been cut by two-thirds over the past 10 days or so. Much of that improvement has happened at the same time that raw vaccination figures have been declining.

Minnesota had some major problems with its vaccine administration a month ago, when the state was averaging around 10,000 shots per day, with doses piling up unused. Things still aren't perfect, with Minnesota trailing the leading states in vaccine administration, and some providers falling far short of the state's goal. But to me, these numbers don't look like a situation driven primarily by low demand or bad administration. At most, those seem to be contributing factors, not dominant factors.

Possible cause: A too-small supply of vaccines

So what about supply then? Is that the culprit? My analysis says — yes. The overriding reason why Minnesota isn't vaccinating more people is that the state just isn't getting enough doses to meet demand.

To me, this graph tells the story in a nutshell: For the past two weeks or so, as daily vaccination rates have been trending down, Minnesota has been on average administering more shots per day than it's received from the federal government.

Over the past week, Minnesota has received an average of just 20,000 doses per day. It's no surprise that we're not sticking 30,000 needles in arms each day any more. Late January saw Minnesota catch up with a big backlog of unadministered doses. Now there just aren't that many vials left in freezers — though there are some.

This is also a sign, by the way, that we might expect vaccination rates to fall further before they improve — eventually, if supply doesn't increase, vaccination rates will have to slow down to meet the available supply.

In the long run, of course, we can expect supply to increase, especially as new models of vaccines get approved for use. But that doesn't help people hoping to get their shots now.

I should add that there's a complication to this analysis that supply is the major factor preventing Minnesota from vaccinating more people. From a policy level, vaccine supply is the one thing that people on the ground here in Minnesota don't have any control over. So it's not surprising that vaccine distribution is the topic that's attracted the most political attention here — even if it only accounts for a minority of the problem now, it's the only lever that state officials can really adjust.