From territory to today: Mapping Minnesota’s Black history

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

In celebration of Black History Month in February, MPR News is highlighting Black history throughout the state. From a fur trader believed to be one of the first African descendants in territory that is now Minnesota, to streets and parks renamed in 2024 after Black community leaders, these sites span the state and the centuries.

Southern Minnesota

Gibbs Elementary School, Rochester

Gibbs Elementary School in Rochester is named after George W. Gibbs Jr., the first known Black person to set foot in Antarctica.

Gibbs was serving in the U.S. Navy when he sailed to the continent as a member of Rear Admiral Richard E. Byrd’s third expedition.

In January 1940, after almost 40 days at sea on the U.S.S. Bear, he was the first person to step off the ship.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

Gibbs moved to Rochester and became a civil rights activist and small business owner.

He spent almost 20 years working at IBM, co-founded the Rochester Chapter of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, or NAACP, and founded an employment agency he operated until 1999.

— Alex Haddon, radio reporter intern

Underground Railroad

Although not much is known about Minnesota’s role in the Underground Railroad due to its secrecy, the Rushford Area Historical Society believes the city was part of the network to help enslaved people to freedom. The area was home to abolitionists at the time and is about 16 miles from the Mississippi River, an escape route north to Canada.

Secret rooms have been discovered in at least three homes in Rushford, which are all currently private residences. One home was built in 1859 for abolitionists George and Harriet Stevens and is thought to be a safe house in the 1860s.

In a different house, a secret room was found downstairs after the flood of 2007. It’s an 18-room, two-story house built in 1861 for Roswell and George Valentine. It is on the National Register of Historic Places.

A third home was built in 1867 for Miles Carpenter, an early Rushford banker, and is also thought to be a safe house.

The Rushford Area Historical Society also believes limestone caves were used to hide people escaping to freedom.

— Lisa Ryan, editor

Central Minnesota

Minnesota Spokesman-Recorder, Minneapolis

As the oldest Black-owned newspaper and one of the longest standing family-owned newspapers in the country, the Minnesota Spokesman-Recorder is a point of pride in the Twin Cities.

The paper was started in August 1934 by civil rights activist Cecil E. Newman with a split publication: the Minneapolis Spokesman and the St. Paul Recorder. In its first issue, Newman made a prediction and promise to readers, writing, “We feel sure St. Paul and Minneapolis will have real champions of the Race.”

Today, Newman’s granddaughter Tracey Williams-Dillard serves as the CEO and publisher for MSR and continues the paper that has been a trusted news source in the Black community for almost a century.

As a weekly paper, MSR has tackled topics like local Ku Klux Klan activities, Brown v. Board of Education, the Civil Rights Movement, Minneapolis’ first Black woman mayor, and George Floyd’s murder.

In 2015, its building at 3744 4th Ave. in Minneapolis became a state historic landmark.

— Kyra Miles, early education reporter

Penumbra Theatre, St. Paul

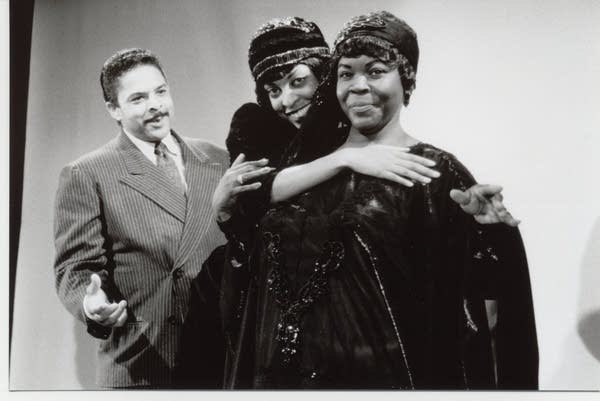

Founded in 1976, Penumbra Theatre was created by Lou Bellamy. Over the years, Penumbra has had the distinction of being the only Black professional theater in Minnesota. The name Penumbra means “half-light” or “partial eclipse.” It was founded using a Comprehensive Employment Training Act grant from the federal government.

Its first production, Steve Carter’s “Eden,” explored diversity of ethnicities within the African American community. In a 1977 interview with MPR News, Bellamy described the theater as being inadvertently political, with its focus on giving Black actors opportunities to perform at the professional level.

“The roles that you generally see — and it’s because of the people who choose the shows — are waiters, butlers, things that if not debilitating, at least are not allowing them to show the extent of their capability,” Bellamy said.

Penumbra has had a number of company members that are recognizable, both locally and nationally. Perhaps its most famous alumnus is playwright August Wilson, who developed some of his earliest plays at Penumbra. In a 2023 interview, Bellamy noted that the character Levee in “Ma Rainey’s Black Bottom” was influenced by his brother Terry’s portrayal in early readings.

In 2021, under the direction of Lou’s daughter Sarah Bellamy, the theater received a $5 million grant to build on its work in racial equality.

— Jacob Aloi, arts reporter and newscaster

Arthur and Edith Lee House, Minneapolis

In June 1931, Arthur and Edith Lee, a Black couple, purchased the modest craftsman-style home in Minneapolis’ Field neighborhood and moved into the predominantly white neighborhood with their young daughter, Mary.

Several years earlier, property owners in the area signed a contract with the neighborhood association to not sell or rent their homes to anyone who wasn’t white.

When the Lees moved in, community members tried to force them out.

Their home became the site of an urban riot in July 1931, when an angry mob of 4,000 white people gathered in their yard and spilled out onto the street, demanding the family leave the neighborhood.

A U.S. postal worker, World War I veteran and NAACP member, Arthur Lee said he had a “right to establish a home” in the neighborhood of his choosing.

Many individuals and organizations came to the family’s defense, including local and national chapters of the NAACP and the prominent civil rights attorney, Lena Olive Smith. (see Lena O. Smith House below)

The Lees stayed in their home until the fall of 1933. According to the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form, the family slept in the basement because of safety concerns, and their daughter Mary was escorted to kindergarten by the police.

The Arthur and Edith Lee House became a designated historic property in Minneapolis in 2014.

The Lee protests remain some of the largest and most widely publicized race-related demonstrations in Minnesota’s history. The city of Minneapolis’ local historic landmark designation similarly finds the Arthur and Edith Lee House to be associated “with broad patterns of social history, particularly in regard to African American history in Minneapolis, race relations and historical trends of housing discrimination.”

— Erica Zurek, senior health reporter

George Floyd Square, Minneapolis

On May 25, 2020, former Minneapolis police officer Derek Chauvin murdered George Floyd outside of a convenience store at the intersection of 38th Street and Chicago Avenue on the south side of Minneapolis.

The community transformed the intersection into a memorial and protest site. It’s also become a point of contention over how to remember Floyd’s murder and the protest movement that started here.

Local protesters maintain that the site should be community-led, until the city meets a list of demands for justice. For a year after Floyd’s murder, protesters kept the streets closed to traffic; city workers took down the barricades in 2021.

Now, the city is locked in an ongoing debate over the square's future. City officials say the streets are overdue for reconstruction. They're pushing for a plan to rebuild the intersection, supported by some local residents and businesses on the block. But local activists, who still maintain the ongoing protest, say it's too soon for the city to take a role in the street design. Instead, they say they want the city to invest in neighborhood services, like housing and substance abuse programs.

— Estelle Timar-Wilcox, general assignment reporter

Hiawatha Golf Course, Minneapolis

At a time when African American golfers were barred from participating in white-only tournaments and golf courses, the Hiawatha Golf Course became a popular gathering spot for Black golfers.

The course opened in 1934 in south Minneapolis, and was the spot, a few years later, where African American golfer James “Jimmie” Slemmons created what’s now the Upper Midwest Bronze Amateur Memorial — a tournament that welcomed Black golfers.

Despite being a popular course for African Americans, the Hiawatha Golf Course clubhouse barred non-white golfers from entering. That is until 1952, when that rule ended, largely because of the efforts of golf legend and trailblazer Solomon Hughes Sr.

“Hughes was an excellent golfer, recognized nationwide, yet still could not golf at white golf courses, which is why Hiawatha golf course is so important to us,” said Greg McMoore, a long-time south Minneapolis resident and historian.

Although once only allowed to play with the United Golfer’s Association, a league formed by Black golfers, Hughes was among the first Black golfers to tee off in a PGA event at the 1952 St. Paul Open.

In 2022, the Minneapolis Park and Recreation Board officially named the clubhouse the Solomon Hughes Clubhouse. The golf course was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 2023.

— Cari Spencer, reporter

Lena O. Smith House, Minneapolis

Civil rights leader and trailblazing attorney Lena O. Smith lived in this Minneapolis home on 3905 Fifth Ave. S. While working in real estate, Smith witnessed up close the discriminatory practices that excluded Black families from certain neighborhoods of the city. She took that experience to law school and in 1921 became the first Black woman to practice law in the state of Minnesota.

As an attorney, Smith took on several high-profile cases fighting segregation and defending the rights of Black residents of Minneapolis. She worked to desegregate spaces in the city including the Pantages Theatre and protected a Black family from a campaign to oust them from their home in a mostly white neighborhood of south Minneapolis. (see Arthur and Edith Lee House, above)

Smith founded the Minneapolis Urban League and led the local chapter of the NAACP as its first woman president. She worked inside and outside of the courtroom to advance civil rights until her death in 1966. Her home was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1991.

— Alanna Elder, producer

‘Spiral for Justice’ memorial, St. Paul

On the south lawn of the State Capitol grounds is the ‘Spiral for Justice’ memorial for Roy Wilkins.

Wilkins, who grew up in St. Paul’s Rondo neighborhood, was a civil rights leader. He worked in various roles at the NAACP from 1931 to1977, leading the organization for 22 years.

The memorial has 46 elements that are positioned in a spiral, getting higher and higher as they extend out from the middle and out beyond two walls that surround the main parts of the sculpture.

Each element represents a year of his work at the NAACP, and the elements breaking through the wall represent progress breaking through barriers of racial inequality. The memorial, designed by sculptor Curtis Patterson, was dedicated in 1995.

— Peter Cox, reporter

Clarence Wigington, St. Paul

The Highland Park Water Tower was designed by Clarence “Cap” Wigington, the first African American municipal architect in the United States.

Wigington designed or supervised the creation of over 130 buildings throughout his decades-long career, with most located in St. Paul and designed during his tenure at the city architect’s office between 1915 and 1949.

He designed a number of city projects including fire stations and park buildings, as well as ice palaces for the St. Paul Winter Carnival. (He also designed my old stomping grounds, Chelsea Heights Elementary School, and an addition to my alma mater Murray Middle School.)

Some of his other landmark structures include the Harriet Island Pavilion (since renamed after him), Roy Wilkins auditorium and the Holman Field Administration building at the St. Paul Downtown Airport.

The Highland Park Water Tower, built in 1928, is one of three Wigington structures listed in the National Register of Historic Places. The others are the Harriet Island Pavilion and the Holman Field Administration building.

— Feven Gerezgiher, reporter and producer

Northern Minnesota

Statue of Tuskegee Airman Joe Gomer, Duluth

A statue in the Duluth International Airport terminal honors a Minnesotan who was a member of the famed Tuskegee Airmen during World War II.

Joe Gomer was among the country’s first Black fighter pilots, flying 68 combat missions in Europe. He and his fellow Tuskegee Airmen were tasked with protecting bombers from German fighters. The unit’s success helped the push to end segregation in the U.S. military.

Gomer stayed in the military after the war and later worked for the U.S. Forest Service in Minnesota. He lived in Duluth for 50 years and stayed active into his 90s. The Duluth News Tribune reported that Gomer shared the history of the Tuskegee Airmen and talked about the importance of education with school groups.

Veterans’ groups in Duluth worked to raise money for the statue to honor Gomer’s service to his country; it was dedicated at the airport in 2012, on Gomer’s 92nd birthday. Gomer died the following year at age 93; he was Minnesota’s last living Tuskegee Airman.

— Andrew Krueger, editor

Hattie Mosley, Hibbing

In 1905, 23-year-old Hattie Mosley moved from Decatur, Ill., to the up-and-coming mining town of Hibbing, Minn. Twelve years prior, the town was established by a German miner.

At the time, 50 percent of Hibbing residents were born in a foreign country. Yet Mosley, a Black woman, remained a minority, as it was still uncommon for Black people to live in northern Minnesota as long-term residents. This is according to history expert Aaron Brown, who was featured in an Almanac interview with Twin Cities Public Television about the resident.

Mosley came to Hibbing as a widow, and did not have any children. She spent the next 30 years as a single woman caring for the mining town as its residents faced the Spanish Flu, the effects of World War I and other daily ailments. She often volunteered in poor immigrant communities and checked in on the sick, using her homemade cough syrup and homemade remedies to nurse most of the town back to health.

She was known to help with the worst cases other medical professionals wouldn’t dare to touch, including the most severe quarantined cases of the Spanish Flu. Because of this, she is described as a heroine and often called the Florence Nightingale of Hibbing, according to Brown.

She died in 1938 and is buried in Maple Hill Cemetery. The beloved nurse and midwife’s obituary said her greatest joy in life was helping those who could not afford care.

“Her acts of charity, so freely given, numbered a legion and among the poor her death will be keenly felt,” read her obituary in the Hibbing Daily Tribune.

Mosley was elected to the Hibbing Historical Society’s Hall of Service and Achievement a decade ago.

— Sam Stroozas, digital producer

St. Mark AME, Duluth

St. Mark African Methodist Episcopal Church is in the Central Hillside area of Duluth. The church was built in 1900 and was added to the National Register in 1991.

W. E. B. DuBois spoke at St. Mark in 1921 before a gathering of the Duluth chapter of the NAACP, which had recently been founded after the lynching of three Black men in downtown Duluth. DuBois founded the national organization in 1909.

— Regina Medina, reporter

Fort Pembina, near present-day Pembina, N.D.

Pierre Bonga and his family are well known in Minnesota’s early Black history, before it was even a state. His son George Bonga was one of the first Black people born in what later became the state of Minnesota, according to MNopedia.

George was born in the Northwest Territory around 1802, near present-day Duluth. His mother was Ojibwe, as were the two women he married in his lifetime. George was a guide and translator for negotiations with the Ojibwe for Territorial Governor Lewis Cass.

While the Bonga family has connections to many locations in present-day Minnesota and the Great Lakes region, they spent time in Fort Pembina, according to the University of North Dakota. Pierre Bonga was also a trapper and interpreter. He primarily worked near the Red River, as well as near Lake Superior. He died in 1831, in what is now Minnesota.

— Lisa Ryan, editor