Inequality even in death: Mankato project finds racial covenants in a cemetery and beyond

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Overlooking the Blue Earth River, Woodland Hills Memorial Park Cemetery sits on a secluded hilltop with the city of Mankato spread below.

It's a quiet green space, but one Minnesota State University, Mankato associate professor Jill Cooley says has a troubled history.

“Racial discrimination doesn’t make any logical sense in any case,” Cooley said. “But a cemetery makes less logical sense than anywhere else.

Cooley and her students found Woodland Hills Memorial Park, formerly Grand View Memorial Park when founded in 1938, has a racial covenant prohibiting nonwhite people from being buried in specific plots within the cemetery. The covenant now has no legal standing following a 1948 U.S. Supreme Court ruling.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

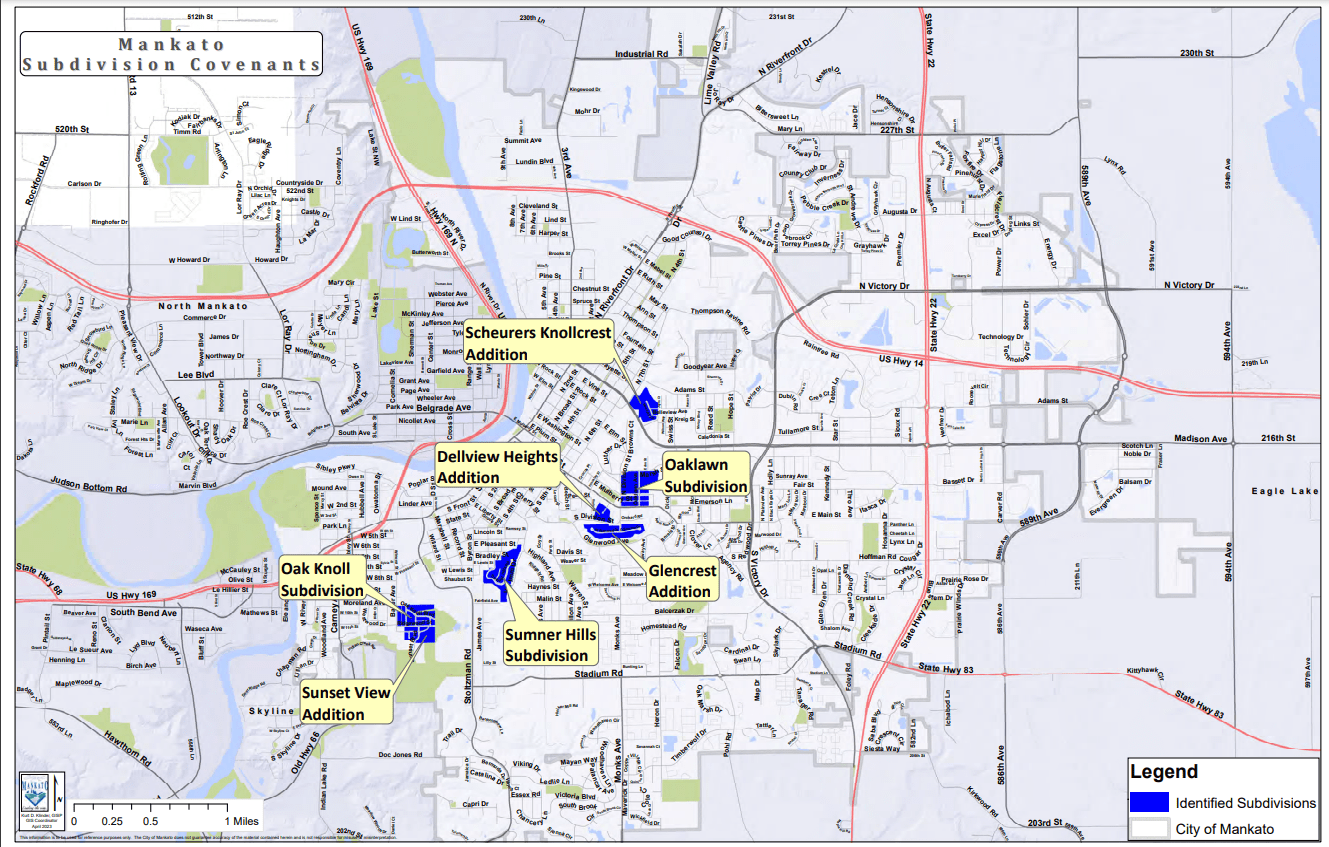

This was a result of a four-year research project by MSU Mankato called “Mapping Mankato Project,” which was inspired by Mapping Prejudice in the Twin Cities. It explored how segregation contributed to how Mankato’s neighborhoods formed and how it impacted generational wealth for marginalized communities.

Enlisting the help of Mankato East High School students, together they read and analyzed deeds, documented covenants and mapped the affected properties. There were covenants found on properties in seven neighborhoods around Mankato.

Organizers hope to expand the research to surrounding communities such as North Mankato and St. Peter in Nicollet County in the future.

‘The system is rigged’

As part of the race, ethnicity and civil rights class, Mankato East High School teacher Tim Meegan connected with the Mapping Mankato Project and got his students involved.

Through the class, students worked directly with property deeds and helped with analyzing them for racial or restrictive covenants. Some were based on class, prohibiting apartments from being built in certain neighborhoods. Others targeted religious communities.

It was a first-hand look at how prevalent housing discrimination was even in Mankato, leading to how some neighborhoods were formed.

“The reason you see disparities is because of racism,” Meegan said. “Racism that goes back centuries, and is hard-baked into American society. The restrictive covenant is just one little piece that shows kids how the system is rigged, and has been rigged to benefit certain groups of people and to oppress other groups of people.”

For Mankato East High School senior Grace Engen, the project hit close to home — literally. She learned her house off of Glenwood Avenue had a racial covenant.

“And it was like, ‘This is real, and this is where I am right now. This is a part of my everyday life,’” Engen said. “You can kind of see it, actually. My whole street is all older white people who have owned these houses for a very long time and passed them down. It’s all our town and it opens up a view of why certain parts of Mankato are racialized.”

It also painted a complex picture of history, highlighting how racial segregation existed in the north and wasn’t limited to just the southern part of the country during the Jim Crow era. Senior Brinley Ketter, who is Black, said it was surreal to physically see the covenants with racial slurs and discriminatory language that targeted different groups.

“It was a way to shut down color in the community,” Ketter said. “A way of putting white power into the collective of the community, as a way of building their power instead of ours. And, that really just wasn’t right to me.”

Meegan believed it was important for stereotypes to be broken, and for his students to understand discrimination. He said housing is the number one way middle class families in the United States build wealth, and racism blocked many people of color for generations.

“I’m a third, fourth generation white American, and my parents were fortunate enough to be able to purchase a home, and my grandparents, and so that generational wealth. That’s a significant source of privilege for me,” he said. “But, if other people were locked out of those same opportunities, that explains why you see such disparities.”

‘We have to do the work’

The Blue Earth County Recorder’s Office houses the copies of real estate records, where researchers and students searched for racial covenants during the Mapping Mankato Project.

Michael Stalberger, property and environmental resources director, said that the county does not have the right to pull off the clauses from property deeds, and only the property owner can pursue discharging them.

“Even though for 70 years, the state of Minnesota said you cannot have these sorts of things on your property, the Supreme Court has said it for just as long, we still have to carry that forward because we don’t have the authority to take [the covenant] off,” he added.

The Mankato City Council voted unanimously on May 22 to condemn discriminatory covenants. Although symbolic, the city does plan to continue pursuing discharging covenants on municipal properties, educating the public about housing discrimination and helping property owners get connected to attorneys who are willing to assist with removing the clauses from their deeds.

City Manager Susan Arntz said that history can’t be changed, but the type of legacy future generations will inherit can.

“My objective is to make sure our words and our actions match,” Arntz said. “If we really think we want to be leading the way as a vibrant, diverse regional community, we have to do the work.”