Chauvin trial judge's advice to colleagues: Take breaks, keep comments short and stay off Twitter

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

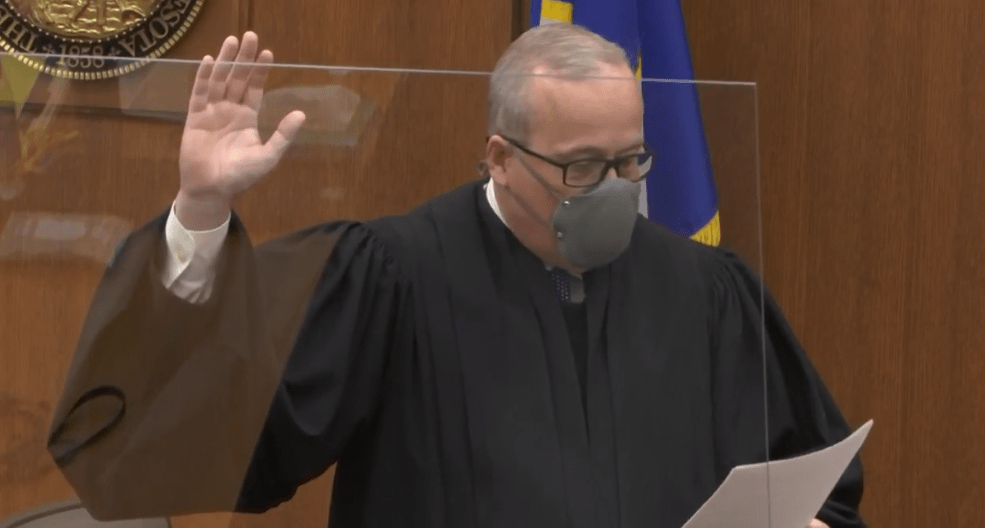

The judge who presided over former Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin’s murder trial last year says that ensuring racial justice in the courts is key to preserving public confidence in the American legal system.

At a conference in Nevada on Monday, Peter Cahill offered candid advice to his colleagues on managing high-profile cases. Among other things, he urged his fellow judges to find ways to manage stress, keep comments from the bench to a minimum and stay off of Twitter.

A Hennepin County District judge since 2007, Cahill said “equal justice under the law,” a phrase inscribed on the walls of courthouses, remains more a goal than an accomplishment. But pursuing that goal is critical to ensuring that Americans trust the judicial system, he emphasized.

“I think we’re getting better. But we are a far cry from being able to say we’ve done it, and rest on our laurels.”

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

Cahill spoke to judges from around the country at the National Judicial College in Reno, Nevada.

In an hour-long talk, he said some of the most dismal failures of the judiciary involved cases with racial justice at their core. Those include the infamous Dred Scott decision, and the Korematsu case nine decades later that allowed the continued wartime imprisonment of Japanese-Americans.

Cahill urged his fellow judges to keep racial justice in mind all of the time — even in matters as minor as a speeding ticket.

“If you’re white, an old white guy like me, and everybody else in the courtroom is an old white guy, even the defendant on the speeding case, you still have to figure out, am I treating this person the same way who is younger, a different age, a different ethnicity, a different race? You have to constantly do that.”

The murder of George Floyd sparked racial justice protests around the world. Though Floyd was Black and Derek Chauvin is white, Cahill said that race was not part of the courtroom evidence. As with most murder trials, he said this case focused on the victim’s cause of death and the defendant’s intent.

Minnesota courts largely prohibit TV coverage, but Cahill ordered an exception for the Chauvin trial because of the pandemic and the enormous interest. The judge said Monday that ensuring public confidence in the outcome was also part of his decision.

“I was convinced that if we did not televise that trial the results, no matter which way it went, were never going to be accepted by the community.”

Cahill gave his fellow judges pointers on how to manage their courtrooms, especially in high-profile cases. One piece of advice: don’t talk too much. Just before playing a clip from the Chauvin trial, he asked the audience to raise hands “when you think I should have stopped talking.”

While watching himself on video converse with a prosecutor, Cahill was quick to raise his own hand.

He added later that when he sentenced Chauvin to 22½ years in prison, he deliberately kept his comments short. Instead the judge released a lengthy memo so the public could understand his reasoning without relying on soundbites.

Throughout the trial, Cahill said he got only an hour or two of sleep at a stretch. He urged the judges to call a short recess if courtroom stress gets to be too much.

“You can say ‘let’s take a five-minute break.’ What remains unsaid is ‘because I have to pace the hall so that I can burn off all this energy,’ because I want to kill that lawyer right now.”

Judges should not seek outside approval of their decisions, particularly from news coverage and especially social media, Cahill advised. One day during the trial he looked at Twitter.

“Yikes,” he said. “It convinced me that Twitter is a cesspool for one thing.”

Cahill said being a judge means managing misery every day — and the vicarious trauma of violent cases takes its toll. After the Chauvin trial, Hennepin County Chief Judge Toddrick Barnette sent him home for two weeks. The court offered counseling for all staff, and special sessions for staff members of color.

Cahill says he’s taking another break before overseeing the trial later this month of J. Alexander Kueng and Tou Thao; the two former officers are charged with aiding and abetting Floyd’s murder.