At a Minnesota evangelical school, Black students sought racial reckoning, then felt the pushback

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Updated: 11:20 a.m.

Dozens of students in rain coats and parkas gathered by a parking lot outside the Billy Graham Community Life Commons on the University of Northwestern campus in November 2020.

Some took shelter from the rain under the school’s columned porticoes. Most of the student body went about their day, climbing steps emblazoned with the names of books of the Bible, or returning to dormitories named for Christian heroes of the school’s past.

A blue pickup truck loaded with speakers backed into a parking space near Riley Hall, named for the university’s founder. Senior Payton Bowdry, 22, grabbed a microphone connected to the speakers and started talking.

After asking God to “unravel the ugly truth, so that we can really be healed as a Christian community,” he began to talk about life as a Black student on campus and how belief in God’s compelling love, spelled out in the university’s vision statement, seemed too often to disappear when he brought up issues of racism and the needs of students of color.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

“BIPOC students have been asking for help for years, but it hasn’t yet been received,” he told the crowd. “BIPOC students are in need. Are we a part of that vision?”

They were asking their peers, teachers and church leaders to recognize and disrupt more than a century of history and theology, to change a way of thinking that had birthed a religious and political movement and a brand of conservatism that continues to define the theology and worldviews of many white Minnesota evangelicals today.

The school, which counts the Rev. Billy Graham among its past presidents, is working on change, said current president Alan Cureton. But he conceded not everyone agrees the university needs to change.

“We’re slowly doing it and I think we’re making progress … but we’re never going to reach utopia, and I keep reminding students we’re a microcosm of a big culture,” Cureton said. “We still have issues … but not everybody in my community believes we have an issue.”

Cureton noted the school, among other steps, had hired a “director of intercultural engagement and belonging” last year. “We’re doing that work, we’re just not using the terms that cause people to get angry about,” he said. “Especially when I’ve got multiple constituencies.”

‘Two worlds’

In interviews, Bowdry and other students of color detailed recurring experiences of casual, exhausting bigotry on the Roseville campus — from tone-deaf comments on race by students and professors to disbelief over claims of discrimination to a kind of passive-aggressive behavior that made them feel unwelcome.

Bowdry and others seeking change that day came with a list of actions they wanted the university to take to improve the campus climate, but they were pressing for more than a diversity office and language changes to university documents.

Among the marchers was Ruti Doto, a 2016 University of Northwestern graduate. In her years at the school, Doto said she frequently ran into conflict with students and faculty members.

She recalled hearing a professor denounce a Black student-led gospel music group as “not Christ-like” and “not real worship.” Another teacher, she said, called her requests for racial justice on campus “diabolical.” A few times, she said, she heard fellow students say they believed Michael Brown — a Black man killed in 2014 by a police officer in Ferguson, Mo. — deserved to die.

“I think there were two worlds at Northwestern,” Doto said. “There were white students who saw Christ as the end-all-be-all, as we should. But it was a blanket over all the injustices that we see people facing. It was, ‘Let’s just pray about it. Thoughts and prayers.’ But then (there’s) the other world where Black students and students of color were continually being traumatized by the racism they experience.”

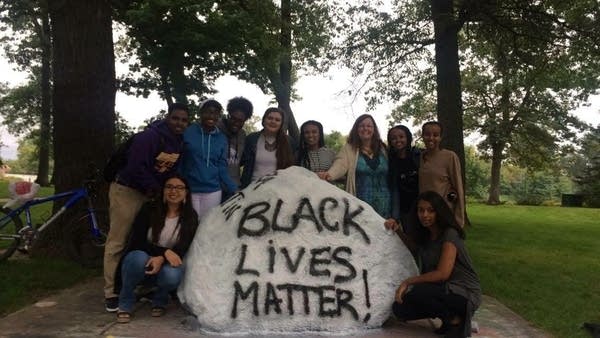

Following the Twin Cities police killing of Philando Castile in 2016 during a traffic stop fewer than four miles from campus, Doto said she and other students painted the phrase “Black Lives Matter” on a rock traditionally used for student expression.

That night, she said, members of the university security team covered the rock and its message with white paint because, as a university official explained later, “it was misinterpreted by the university as a political statement.”

Doto said she and others returned the next day to repaint “Black Lives Matter” on the rock but discovered a group of students had blotted out the word “Black” and wrote “All” there instead, turning the phrase into “All Lives Matter.”

In June of 2020, when she saw a picture of the rock on Instagram, newly painted with the phrase “Black Lives Matter,” it felt to her like the university had forgotten its actions four years earlier.

“Of course, this triggered me and multiple students of color,” Doto said. “When we did this, you all painted over it and we were dismissed. You didn’t care for what we had to say. Now that it’s the trending topic is when you decide to speak up. But what really angered us is … there wasn’t any meaningful actions. It was just painting the rock.”

Doto and some of her fellow alumni drafted a petition in response, suggesting a list of “measurable actions to support students and address institutional racism” at the university.

“I have a ton of Black high school students who ask me if it’s a place they should consider. And my truthful answer now is no,” Doto said. “And I want to get it to a place where I can say it’s a great place that you can be part of.”

Thousands of supporters added their names to Doto’s online petition, some with their own stories of racism they’d experienced at Northwestern. One person wrote about resident assistants hanging a Confederate flag in a dorm hallway as decoration. Another wrote of people on campus referring to Obama as the anti-Christ after his reelection.

“This place was supposed to be my community,” one signer wrote. “Instead I was reminded of how much I didn’t fit in or belong … most of the passive aggressive racism that I’ve experienced came from this school.”

When Bowdry, the student who led the protest on campus, returned to campus in the fall of 2020, he and his fellow students used Doto’s petition as a framework to guide their list of demands.

They asked university leadership to establish a diversity, equity and inclusion office, mandatory anti-racism training for faculty, staff and students, core courses on Black, Native, Latino and Asian theologies and histories, a zero-tolerance policy on racism, a George Floyd memorial scholarship for aspiring Black American leaders and language in the university’s Declaration of Christian Community requiring students and staff to condemn racism.

“We are no longer willing to endure our campus’s compliance with racism,” they wrote. “For too long, the interests and desires of our white counterparts have been held at a higher consideration. The Gospel of Jesus Christ that we have placed our faith in is incomplete without the commitment to restore justice in our world.”

‘Even if they’re trying to understand you, they don’t’

Kenneth Young is one of the first full-time African American faculty members hired at the University of Northwestern. He’s been at the institution for close to 30 years and teaches systematic theology and Christian ministries. It’s a job he dearly loves at an institution he considers a good fit.

“They pay me to teach the Bible!” he said, laughing.

Young, though, said he’s had unpleasant run-ins with students and colleagues during his tenure, and he knows students of color there have also had bad experiences.

“I don’t think it’s those overt experiences of marginalization or even racism that is discouraging them. I think that there’s a gap, a hole in the European American evangelical Christian worldview that students of color sense … there’s a lack of empathy,” he said. “Not because the European American students are bad or racist but because there’s a gap in their worldview … even if they’re trying to understand you, they don’t, and so you feel marginalized.”

It’s a problem grounded in teaching from Sunday School classes to Bible colleges, he said, noting that Blacks were largely excluded from the Bible college movement.

“The people who were teaching had no clue. This space, this worldview space, is just rampant within the context of the greater Christian community and it leaves us with a gap, with an inability to communicate with each other.”

Young said he prefers not to use the terms “racist,” “Black” or “white.” Instead, he speaks of geographic origins, cultures and worldviews. For him, the problems he and students of color have experienced at Northwestern are based in theology and ideology with a long history in the evangelical church “that make us vulnerable to complicity in social injustice.”

He said he tells students two things: “We need to learn how to have real dialogue and we need to enter that dialogue with a high degree of humility. Critical thinking, having dialogue, you gotta be able to consider what somebody else is saying … let it really sink in.”

Many Christian colleges and universities now brand themselves as conservative “and that’s really part of their identity,” said Jemar Tisby, a historian who has written extensively on the history of racism in American Christianity. So it’s a lot harder for these institutions to change because their institutional vitality depends on them not being progressive in any way.”

These institutions were not founded with racial or ethnic diversity in mind, and that works against social progress, Tisby said. “It’s much more about a social, political identity than it is about a religious identity.”

For David Fenrick, who worked at the University of Northwestern from 2008 to 2019, the experiences of students of color on campus like Bowdry and Doto are directly linked to the school’s history.

“It’s a historically white institution, a very conservative evangelical school. And the experience of students of color there was not very positive. They felt that their voices weren’t heard, their culture wasn’t recognized, their perspectives weren’t validated. Sometimes there was open hostility,” said Fenrick, who served as director of the school’s Center for Global Reconciliation and Cultural Education.

He could remember many times students would come to him with stories of bad experiences. That includes an Ethiopian Orthodox student who spoke up in a theology class to offer his perspective. The student said the instructor was dismissive, Fenrick recalled — “‘Well, that’s great, but we’re not here to study Black theology,’ … or ‘We’re not here to study Ethiopian Orthodox theology. We’re here to study Christian theology.’”

For Fenrick, those kinds of stories illustrate the problem at the University of Northwestern.

“There’s a kind of welcome (at Northwestern) that says, ‘We’re glad you’re here, now be like us.’ That’s what they (students of color) were experiencing. What they wanted is a place to say, ‘Welcome, we’re glad you’re here, let’s all be who we are, the way God made us in our cultures and our gifts, our abilities and our experiences.’”

The school was founded in 1902 as a Bible and missionary training school by Baptist pastor and evangelist the Rev. William Bell Riley. Riley was also politically active and focused much of his attention on trying to get the teaching of evolution banned from public schools. He has also been accused of antisemitism for his writing and speeches that blamed a “Jewish Bolshevik conspiracy” for a variety of social and economic ills.

Randy Moore, a biology professor at the University of Minnesota who’s studied Riley’s influence, points to Northwestern’s founder as a father and organizer of the Christian fundamentalist movement.

“What came to be known then as ‘fundamentalism’ — contrary to most people’s knowledge of it now — originated in the north in towns like New York City and Minneapolis and Chicago,” Moore said.

“He tapped into this discomfort that what we now call fundamentalists had with the direction of the country … and he organized it,” Moore said. “And it was militant. That was very unusual. Now it’s very common — Jerry Falwell or Pat Robertson. There’ve been others, but you can trace them back to William Bell Riley.”

Riley was succeeded in his leadership by Graham, who was president of the institution for four years.

For the Rev. Curtiss DeYoung, CEO of the Minnesota Council of Churches, the histories of Graham and Riley offer clues to the difficulty modern-day white evangelicals have when it comes to dealing with racism.

On a personal level, DeYoung points out, Billy Graham abhorred racism and refused to hold segregated rallies. But, although he invited Martin Luther King to pray at his crusades, Graham was not involved in the civil rights movement.

“If your priority is just to convert people to Jesus so they can go to heaven, you have less of a focus on the systems that exist right now because you’re thinking about eternity. Therefore these systems continue to exist and reproduce themselves,” DeYoung said.

For historian Tisby, this individualistic theology is at the crux of white evangelicals’ inability to deal or make progress on many social issues, including race. The problem is compounded at institutions like Northwestern.

“White evangelical colleges and universities are more individualistic than the larger society. They’re focused on maintaining the status quo and racial justice is not within the scope of what they’re looking at,” Tisby said.

‘Our beloved University is at a turning point’

The changes pushed for by students of color at University of Northwestern in the last several years have also brought protest from students, staff and the wider evangelical community. Last year, a group of conservative students on campus released a petition, condemning anti-bias training, curriculum changes and the new DEI position, among other initiatives.

“Our beloved University is at a turning point,” the petition authors wrote, “Perhaps more significant than any other in its history.”

The petitioners objected to the university including cultural competency in curriculum, mandating racial bias training for staff, funding a diversity and inclusion office and sponsoring campus-wide events promoting “reconciliation” among other things and suggesting that the school was implicitly endorsing critical race theory or social justice, leading down a road to Marxism or other “anti-biblical ideologies.”

The petition authors took their concerns to Fox News, saying “as Christians we believe our primary call is to preach the gospel. And we firmly believe Critical Race Theory is unbiblical and that it preaches a different gospel.”

The petition was reviewed by local pastors then published online. It has since been signed by thousands, many of them raising concerns about critical race theory in schools. One threatened to withhold financial donations to the school “unless things turn around.”

‘Still really harming people’

Conditions have improved during Kenneth Young’s time at Northwestern. While the percentage of students of color remains less than 20 percent, it’s grown from about five percent the past two decades.

Close to a decade ago president Cureton oversaw the preparation of a “strategic diversity and inclusion framework,” which included directives such as examining “systems that may be preventing full diversity, equity and inclusion” and intentionally increasing “the diversity of students, faculty, staff, administrators and board of trustees.” The framework was affirmed by more than 90 percent of the school’s faculty and unanimously adopted by the university’s board in 2018.

And there were changes that the university made in response to the protests and demands of students of color like Bowdry and Doto in 2020.

Student body president at the time, Qashr Middleton, helped shepherd those demands into action.

Middleton, a 24-year-old from Colorado pursuing a degree in ministry leadership, was the first student body president of color in Northwestern’s history. He stepped into his role in the summer of 2020, after spending weeks protesting the murder of George Floyd, getting chased by white supremacists, tear-gassed by police officers and almost getting run down by a semitrailer on the Interstate 35W bridge in Minneapolis.

When he tried to talk about his experiences on campus, he felt like it made some white students and staff on campus uncomfortable.

“It’s hard to tell that story at Northwestern. Because you really get to see people’s conflict of interest within themselves. Because now you’re telling a personal story. And they know your character. You peacefully were protesting and almost got hurt. And yet they still were able to find a way to say, ‘Well, what about this?’” Middleton said.

After the 2020 student protest, Middleton organized a student government committee to begin working on those and the other demands.

Eventually, the school inserted phrases into its Declaration of Christian Community, requiring students and staff for the first time in its history to commit to “refrain from racism, prejudice, and social injustices” and “condemn oppression which can manifest itself in individuals and systems.”

Leaders did not create a “George Floyd memorial scholarship” as requested by students, but they did endow a scholarship geared toward students planning to work with “urban youth leadership” or “biblical reconciliation.”

There is anti-bias training for faculty and staff at Northwestern, although attendance is not required because, as Cureton said, “You can’t force people. It may appease people (saying) you’re required to go, but it doesn’t work.”

The university president, who’s set to leave his position this year, has said he believes it’s the school’s job to help students and staff learn how to “live amidst multiple cultures” — something he believes is integral to the university’s mission of “reflect(ing) the essence of the Kingdom of God.”

He does not believe the university has a “culture of racial intolerance.” But he concedes his community falls short.

“Are there acts of insensitivity exhibited by some towards people of color? Yes. Is learning to live amidst multiple cultures a learning process? Yes.” Cureton said. “We still have a ways to go. But acknowledging that we have a ways to go, acknowledging that we still have issues — that’s a huge step. But not everybody in my community believes we have an issue.”

Katy St. John, 21, who graduated from Northwestern in May, said she has a hard time understanding why Northwestern students and faculty are not more wholehearted in embracing change.

St. John, who is white, is a pastor’s daughter. She grew up leading youth group programs and going on mission trips. As an incoming freshman, she’d been excited about Northwestern’s beautiful campus, and the opportunity to grow her faith there as she studied communications and sang in the chapel on the worship team.

Her first year on campus was filled with good memories, but she soon became worried by what she saw and heard. A white professor, she said, insisted it was OK to say the n-word. White students questioned her relationship with students of color asking, as she put it, “Why are you friends with those people?”

When St. John expressed her frustration to other white students about professors who said “ignorant things” about race, she was surprised at those students’ reactions.

“It ended up blowing up in my face a lot where they misunderstood what I was saying, took it very personal, and they got very, very angry at me and told me that I was racist towards white people,” St. John said.

In 2020 St. John helped organize the protest and the list of demands with students of color. She’s pleased that some of the demands they made were met. And she has glowing reports of individual people she thinks are fighting hard to change things at the school. But overall, she doesn’t think enough change has been made.

“There’s ways I’ve seen Northwestern grow. Very tiny little pieces that feel like they’re doing a good job … (but) they’re also working under people who are not prioritizing it the same way and still are prioritizing whiteness and white feelings,” St. John said. “The institution is systemically still really harming people. There are people I know who’ve left here who act like (they have) actual diagnosed PTSD from being here as a student of color.”

Even more difficult to understand for St. John is the way in which her fellow white students are pushing back on racial justice.

“The liberation of Black people is liberation of all of us,” St. John said. “There’s this concept that when whiteness has its privilege and its power and its position stripped from it, then we’ve lost, we’ve fallen … but the reality is, is what we get is so much better. What we get is the opportunity to be human, to see other people as human.”

St. John said her experiences on campus have challenged her faith.

St. John’s roommate, Kiera Sconce, feels similarly. A 21-year-old Black woman, she also graduated in May. The school’s racial and ethnic affinity groups are where she grew, learned and made friends. But outside of those groups, she said she didn’t feel safe to be herself or say what she thought.

She said she and some of the other students of color she knows at Northwestern spent their last semester in 2022 isolating themselves, keeping their heads down in class and escaping back to their rooms or other places they could be alone afterward.

“There is very little time when I feel or felt seen on this campus. Whether it’s by professors or it’s by other students. They don’t know you,” Sconce said. “A lot of students of color tend to hide at Northwestern.”

Editor’s Note: University of Northwestern is a financial supporter of MPR News.

Correction (May 26, 2022): An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated where Qashr Middleton is from and the degree he is pursuing. The story has been updated.

Correction (June 5, 2022): An earlier version of this story incorrectly stated the location of the campus rock used for student expression. The story has been updated.