Wildfire smoke causing 33-percent fewer blue sky days in Minnesota summers

Minnesota and the Dakotas seeing 9 to 12 smoky days per month between June and September

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Minnesota skies are not as blue as they used to be.

A 2018 study in the journal Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics finds 9 to 12 days per month between June and September with smoke plumes overhead in the Upper Midwest.

The map above clearly shows Minnesota and the Dakotas are the epicenters of wildfire smoke plume frequency.

Fig. 1 shows that during summer (June–September) over the contiguous United States, North Dakota, South Dakota, and Minnesota have more smoke plumes overhead than any other states, averaging between 8 and 12 days per month between June and September.

Climate change increasing western wildfires

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

So where are our more frequent smoky skies coming from?

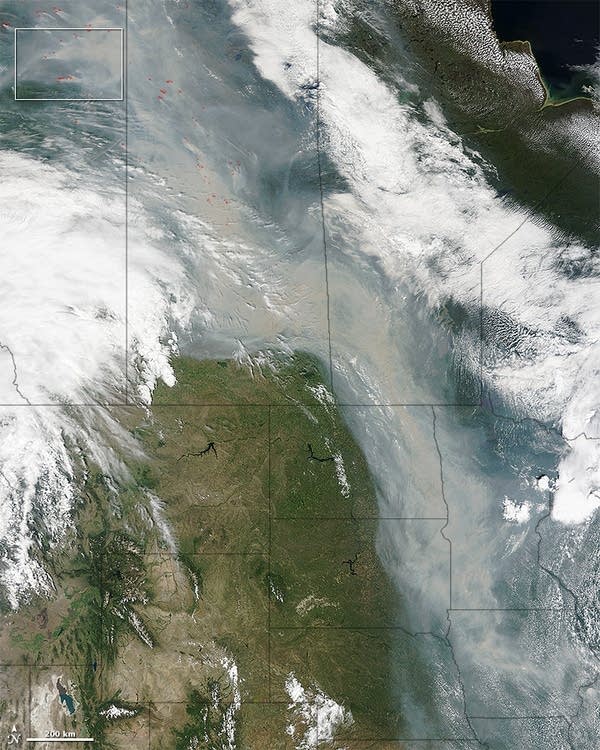

It’s clear from satellite images and trajectory analysis that the bulk of these plumes originate from wildfires in the western U.S. and Canada. And studies show climate change is increasing the number and size of wildfires in the western U.S. and Canada.

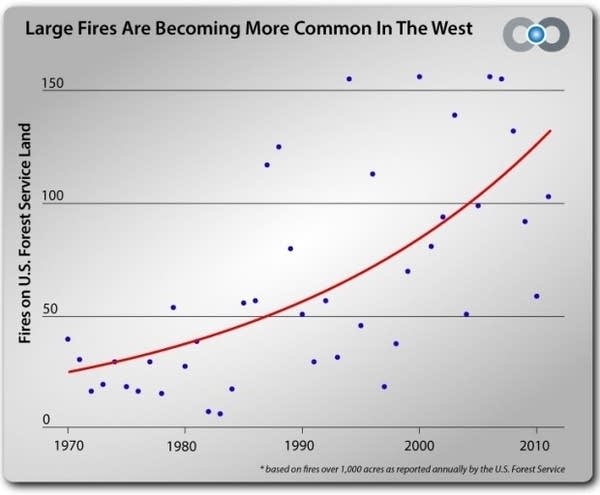

The number of large fires over 1-thousand acres in the western U.S. has more than tripled since 1970.

Minnesota is downwind

The extra smoke from wildfires in the western U.S. and Canada often drifts aloft downwind toward Minnesota. That produces more smoke days that obscure Minnesota’s traditionally blue summer skies.

From blue, to white

I’ve written many times in recent years about how wildfire smoke aloft is obscuring Minnesota blue skies. Elevated smoke layers scatter sunlight and leave a milky white tone across the sky.

Smoke reaching ground level too

Smoke particles at ground level are detected by sensors that the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency (MPCA) deploys. And the number of air quality alerts issued by the MPCA for ground-level smoke has more than doubled in the past decade.

Here’s more from the MPCA.

If it seems like the number of alerts due to wildfires has increased in the past few years, you’d be right. According to MPCA’s staff meteorologists we’ve had 26 air-quality alerts since 2015, and 14 of those were due to wildfire smoke. That’s nearly double the number of smoke-related alerts the MPCA called in the previous seven years.

It’s one thing to get smoke impacts from home-grown wildfires, but in recent years we’re getting hit with smoke from fires burning more than a thousand miles from here.

Long-range transport

Thick smoke plumes from massive western wildfires in the U.S. and Canada shoot miles into the atmosphere. Once aloft, they quickly blow downstream on mid-level winds. It only takes a couple of days to reach Minnesota.

“These are long-range transport events,” says MPCA meteorologist Daniel Dix. “We’re just seeing many more bigger, hotter fires that generate these kinds of air-quality impacts for Minnesota.” While the massive fires in California are the ones we hear about, Dix said the fires that are dimming the sun in Minnesota this year have been mainly in British Columbia. (However, we are now seeing smoke from wildfires due north of Minnesota in western Ontario.)

“The California smoke is mainly blocked by terrain between us and them. But the fires in Canada are also huge, and when we get cool fronts from the Northwest, we’re right in the path of those plumes,” Dix said.

Breathing trees

Wildfire smoke contains what air quality experts call fine particulates. These particles are so tiny we can easily breathe them into our lungs. When we do, we’re breathing in what used to be trees and other things like homes that were incinerated by the intense blazes.

According to Steve Irwin, also an MPCA meteorologist, smoke from wildfires contains a variety of pollutants that are problematic for human health. “Smoke contains carbon dioxide, water vapor, carbon monoxide, particles, hydrocarbons, other organic chemicals, and nitrogen oxides. But the pollutant that’s the most concern is fine particles. Those are the ones that seem to do the most damage to the lungs and the heart.”

Fine particles, called PM2.5, are really small, with diameters of 2.5 micrometers and below. For comparison, a human hair is 50 to 70 micrometers in diameter.

PM2.5 has significant health effects, not just on the respiratory system but the cardiovascular system as well. When levels are forecasted to be in the orange range on the Air Quality Index, the MPCA calls an air quality alert. “Anyone can be affected depending on their level of activity,” Irwin said, “even if it’s a healthy person but they’re outdoors breathing hard and exerting themselves. But generally it’s going to be sensitive populations, those with lung conditions such as asthma or COPD, heart disease or high blood pressure, children and elderly.”

So as fire season gets going in western North America this year, expect to see more smokey skies above Minnesota once again this summer. And you can connect our smokier skies to climate change.