How to make high school more interesting? Here's an idea

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Andre Keller is a senior at White Bear Lake High School. He hates sitting still, and loves working with his hands. That would put him in the same league with many of his peers, who a 2016 Gallup Poll described as not engaged by traditional classes in high school.

On a recent Friday Keller took a break from a study session to step into the school's shop room. There, in addition to the usual woodworking tools and drills, were several enormous industrial-grade pieces of manufacturing equipment worth tens of thousands of dollars.

As he designed, measured, milled and tooled a piece of metal that could be used for injection molding, Keller was using trigonometry. But he wasn't thinking about trigonometry. He was thinking about the danger of working with a huge piece of equipment.

"Since there is a danger factor in it, because you can get hurt, that also encourages people to do it. So, that's probably the fun part," he said.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

The work engages Keller's mind. He knows he needs to pay attention to the safety protocols and the math he needs to design and measure materials. He's also connecting what he's doing in class to the real world. He knows that the skills he's learning translate directly into safety and productivity for himself and others.

Keller's manufacturing class is part of White Bear Lake High School's Career Pathways program. It's an effort to partner with local employers to design classes, field trips, job shadows, paid internships and college credit options that give students a banquet of opportunities. Right now there are four pathways: construction, health care, information technology and manufacturing.

Bela Larsen, another student in White Bear Lake's manufacturing pathway, said her classes in the program are different from other high school classes.

"It's not somebody sitting you down in a classroom lecturing at you every day," she said. "It's not something that you sit down and take notes on forever ... I feel like they trusted me a lot more. They were like, 'You know, you're gonna mess up. But we're here to teach you, so you have room to make mistakes.'"

The way Larsen and Keller describe their classes goes to the heart of what researcher Sarah Fine calls "deep learning." She and her co-author, Jal Mehta, are out with a new book called "In Search of Deeper Learning: The Quest to Remake the American High School."

After studying dozens of high schools, they have a recipe of sorts for powerful learning: classes in which students were treated as people who could solve problems and produce something valuable. Classes that were purposeful and connected to the real world. And classes in which students had agency and weren't just "empty vessels" waiting to be filled with knowledge from the adult in charge.

"There is something of consequence that you're creating," Fine said. "You're doing it together where you have differentiated roles, opportunities for apprenticeship, older, more advanced students teaching younger ones. Adults are not dispensing knowledge, they're kind of coaching along the way."

Larsen, the White Bear Lake senior, said many of her classes involve studying to write an essay or pass a multiple-choice exam. But in an engineering and design class she took in the manufacturing pathways class, the exam was very different.

"Our final wasn't reading an essay and writing a paper on it, it wasn't a multiple-choice packet of questions. It was 'OK, guys. Here's a part that was taken out of production. Measure every single bit of it ... and then I want you to tell me why you think it was taken off the market, what you think didn't work about it,'" she said. "It was cool because all of us could use our own talents and our own ways of thinking to get to the same end result."

Larsen has since decided she wants to go into industrial manufacturing and engineering management to, as she put it, "hopefully become someone's boss someday." She started high school thinking engineering wasn't an option for her, because she didn't think she was good enough at math. Now she's planning to attend the South Dakota School of Mines and Technology next fall.

Researchers recommend that students be treated as people capable of contributing something of value to the world. Students in the certified nursing assistant (CNA) program, for example, know that their work will make a real difference.

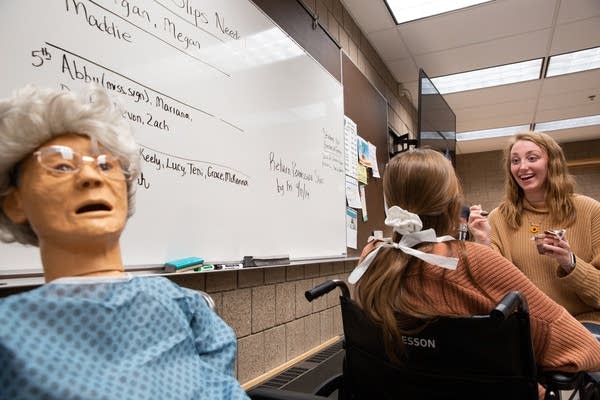

Victoria Wilson is a junior enrolled in the CNA program this semester. She's taking classes from nurse Janaye Stewart with mannequins, wheelchairs and hospital beds that allow her to learn about long-term care.

But next month, Wilson and 67 other White Bear Lake students are heading to Cerenity Senior Care, a local health care facility. They'll have more training and opportunities to actually take care of people and pass a state certification class. They'll also have the chance to get a summer and after-school job, if they want. Wilson and other students will see all their studies and training pay off in work that actually makes a difference to people in their community.

White Bear Lake's Career Pathways program isn't just providing students an opportunity for deep learning. It's also thinking ahead to matching them with a job they like that will pay them a livable wage.

Sareen Dunleavy Keenan, the program officer for career academies at the Greater Twin Cities United Way, has been studying and supporting White Bear Lake's Career Pathways program and similar initiatives at 16 other Minnesota districts. She said the initial data shows an actual increase in earned wages after graduation. And it's not just about money:

"If you make high school more relevant, if you make high school more interesting, do they have the ability to identify themselves as a leader in how this will impact their future work? Our research shows that students see that," she said.

Keenan said programs like the one at White Bear Lake are also proving to be more equitable. They're giving students more power and responsibility in the classroom. And they're not just connecting students to a job. They're giving them the skills to succeed in whatever they decide to do.