Explaining the Jacob Wetterling case: Where it stands

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

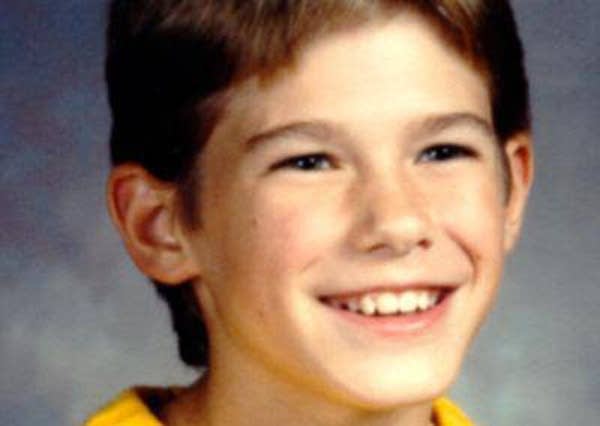

The disappearance of Jacob Wetterling remains one of the highest-profile child abduction cases in U.S. history.

Wetterling was 11 when he was abducted by a masked man with a gun on Oct. 22, 1989, in St. Joseph, Minn.

He had been biking home with his brother and a friend when a masked man with a gun stopped them and told them to get off their bikes and lie face-down in a ditch.

After telling the man how old they were, 10-year-old Trevor Wetterling and 11-year-old Aaron Larson were told to run away. They never saw Jacob again.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

Hundreds of Minnesota National Guard members, law enforcement officials and volunteers searched for Wetterling in the days after his disappearance.

It was one of several child abduction cases that changed how Americans raised their children: Before Jacob Wetterling went missing, "stranger danger" wasn't a part of parents' vocabulary. AMBER Alerts, which broadcast urgent bulletins when a child is abducted, didn't exist in 1989, and sex offenders were not required to register with the government.

The case remains open.

What's the latest?

On Thursday, Oct. 29, federal authorities announced they had charged Daniel James Heinrich, 52, with possessing child pornography after gathering evidence in a search related to Wetterling's disappearance.

Heinrich has not been charged with any crime directly connected to Wetterling.

But investigators say they consider him to be a "person of interest" in the Wetterling abduction. The FBI said Thursday that shoe patterns at the site where Jacob Wetterling was abducted match Heinrich's shoes. Officials said the tires of Heinrich's car at the time were consistent with tread marks on the scene.

Heinrich was investigated in 1990 in the Wetterling case but investigators are only now making his name public.

Authorities also said DNA evidence links Heinrich, who is from Annandale, Minn., to another central Minnesota child assault case in the Cold Spring area less than one year before Wetterling's abduction.

Heinrich has denied any involvement in Wetterling's disappearance.

The Wetterling family is asking anyone with information about Heinrich's activities back in 1989 to contact the Stearns County Sheriff's Office.

Why is the Wetterling case so important?

The Wetterling abduction horrified parents across the country.

In 1994, five years after Jacob Wetterling's disappearance, Congress passed the Jacob Wetterling Crimes Against Children and Sex Offender Registration Act as part of the sweeping Violent Crime Control and Law Enforcement Act, originally written by then-Sen. Joe Biden, D-Del., and signed into law by President Bill Clinton.

The Wetterling Act required states to register and track sex offenders for ten years after their release from prison. It required prisons to alert other agencies when sex offenders are released, and it made failing to register a crime. The law also increased the maximum federal sentence for repeat sex offenders.

The Wetterling Act was amended by Megan's Law in 1996, which required states to not only register sex offenders, but to make the information publicly available and part of community alerts.

Why isn't Heinrich being charged in the Wetterling case?

Minneapolis criminal defense attorney Joe Tamburino said authorities would need a direct link to Wetterling at the time of his disappearance to charge Heinrich with kidnapping or murder.

Investigators recently tested a sample of clothing worn by the boy assaulted during the Cold Spring incident and found DNA on the sample that matched Heinrich.

That gave police enough evidence to obtain a search warrant for Heinrich's Annandale home in July. During the search, officials found hours of video they say Heinrich secretly recorded of of boys in his neighborhood. They also found computer files and 19 binders containing pornographic images of children.

Heinrich is being charged with possessing child pornography. U.S. Attorney Andrew Luger said Thursday the statute of limitations on the Cold Spring incident has expired. The Wetterling investigation, he said, remains active.

"I want to remind everyone that Mr. Heinrich is not charged in the disappearance of Jacob Wetterling," Luger said Thursday. "The charges against this defendant involve serious federal violations of the child pornography statute. And he faces significant prison time if convicted on those charges."

Have there been other leads in the case?

Daniel Heinrich isn't the first to be named a "person of interest" in the Wetterling case.

Jacob Wetterling's disappearance has resulted in 50,000 leads in the past 26 years.

In 2010, Stearns County Sheriff John Sanner helped lead a search of the Stearns County farm belonging to Rita and Robert Rassier, which abuts the road where Wetterling was abducted.

It was the fourth time the farm had been investigated, according to a family member. No charges or arrests resulted from the search. Dan Rassier, who was publicly identified as a person of interest in the case, but has not been charged, said in 2012 that law officers had violated his civil rights and his family's rights and "abused the privileges of their power" in the investigation.

"Is it considered legal for law enforcement to give the public the perception I am guilty of something when I'm not?" Rassier wrote in a letter to several state officials and agencies.

In 2014, Stearns County investigators looked at several stranger assaults that took place in nearby Paynesville in 1986 and 1987. There were at least five assaults — and the victims were all teenage boys.

This isn't the first time Heinrich has been on investigators' radar.

Documents released Thursday show that in January 1990, a little more than two months after Jacob Wetterling's abduction, Heinrich gave investigators his shoes and let them remove tires from his car and that the shoes and tires were found to be a match with shoe and tire marks at the abduction site.

"I can tell you that Mr. Heinrich was looked at very closely back in 1989 and 1990, so this isn't somebody new to us," Sanner told reporters Thursday.

How is this all connected to the MSOP?

In 1994, five years after Jacob Wetterling's disappearance, Congress passed a crime bill that included the Jacob Wetterling Crimes Against Children and Sex Offender Registration Act, which required states to register and track sex offenders.

A year after the law was passed, the Minnesota Sex Offender Program opened a corrections facility in Moose Lake to treat and house convicted sex offenders.

The state's treatment of sex offenders stands out among the 20 such programs across the nation, with the highest per capita lockup rate and just a handful of offenders provisionally released to community-based settings.

While offenders in California, Wisconsin, New Jersey and other states are allowed to re-enter society after completing treatment, no one has been fully discharged in Minnesota.

This week, a federal judge took a suggestion offered by currently committed offenders and ordered a risk assessment of all sex offenders in Minnesota to determine who can be put on a pathway for release. In June, that same judge ruled the program unconstitutional, saying it's illegal for Minnesota to keep civilly committed sex offenders locked up indefinitely.

State officials, however, argue the program is properly holding more than 700 offenders they consider too risky to free.

How has this changed the way we treat cases of missing children?

Wetterling's disapperance, along with the cases of Etan Patz in 1979 and Adam Walsh in 1981, garnered national attention — and changed the way American parents raised their kids.

After such high-profile abductions, parents in the late '80s and early '90s were trained to think twice before allowing their children to play outside by themselves, or after dark. President Ronald Reagan established the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children, which, along with the FBI, maintains a database of missing kids across the country, in 1984.

After her son's disappearance, Patty Wetterling became a nationally known child safety advocate. In 1990, Patty, her husband Jerry, and a handful of friends and supporters established the Jacob Wetterling Foundation, which later became the Jacob Wetterling Resource Center, to help protect children from abduction and sexual exploitation. The organization raised awareness of "stranger danger," which soon became a mantra among parents and educators.

The Wetterlings and their three other children say they have learned to survive and cope through the years while never losing sight of the possibility that Jacob could turn up alive.

"That's the grandest hope, and it's certainly there," Jerry Wetterling said in 2009, on the 20th anniversary of Jacob's disappearance.

Patty Wetterling went on to advocacy and politics after her son disappeared. She lost a bid for the 6th Congressional District in 2004 and entered the 2006 race for then-Sen. Mark Dayton's seat after he announced he wouldn't seek reelection. She later withdrew her candidacy and supported Amy Klobuchar, the eventual winner.

Wetterling directed a program on sexual violence prevention at the Minnesota Department of Health for seven years, a job she left in May. She chairs the National Center for Missing and Exploited Children's board of directors.

MPR News reporters and the Associated Press contributed to this report.

Correction (Oct. 30, 2015): An earlier version of this story attributed the DNA evidence to the wrong assault case. It was DNA evidence from the Cold Spring assaults that led investigators to search Daniel Heinrich's home. The story has been corrected.