Founder of MIA's photography department has died

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Photographer Alec Soth says he won't remember Ted Hartwell as a curator, but as a photographer.

"What I think about with Ted is really his passion for being a photographer and for the photographic life, the stories of the photographers he met or the cameras," says Soth.

Hartwell got his training as an aerial reconnaissance photographer, stationed in Korea and Japan with the U.S. Marine Corps in the early 1950s. After his military service he continued taking pictures, and even returned to Japan for an independent photography project.

The MIA hired Hartwell in 1963 to take pictures of the art for the archives. Over time, he convinced the museum leaders that photography was worthy of their attention as an art form in its own right.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

Nearly a decade later, the museum appointed him curator of photography and gave him permission to start a permanent collection. In a 2004 interview, Hartwell recalled those early days, remembering how novel the idea of photography as art was to both museums and the general public.

"They sort of tolerated it. They felt it was interesting, it was popular," said Hartwell at the time. "It got a lot of the public into the museum -- increased the head count."

One of Hartwell's most controversial and high-profile exhibits was the first retrospective of Richard Avedon's work in 1970. Avedon was primarily a fashion photographer, known for shooting the Paris collections for Harper's Bazaar and Vogue. But Hartwell thought that Avedon deserved to be considered with a more serious eye.

Associate Curator of Photography Christian Peterson, who worked side-by-side with Ted Hartwell for 27 years, says the Avedon retrospective was a perfect example of Hartwell casting the net wide when looking for photographic art.

"When I started, the department subscribed to Rolling Stone magazine because of the photographs that were being published, and to The Village Voice. He really became a champion in the '80s and '90s of photojournalism as something worthy of a creative discipline," Peterson says.

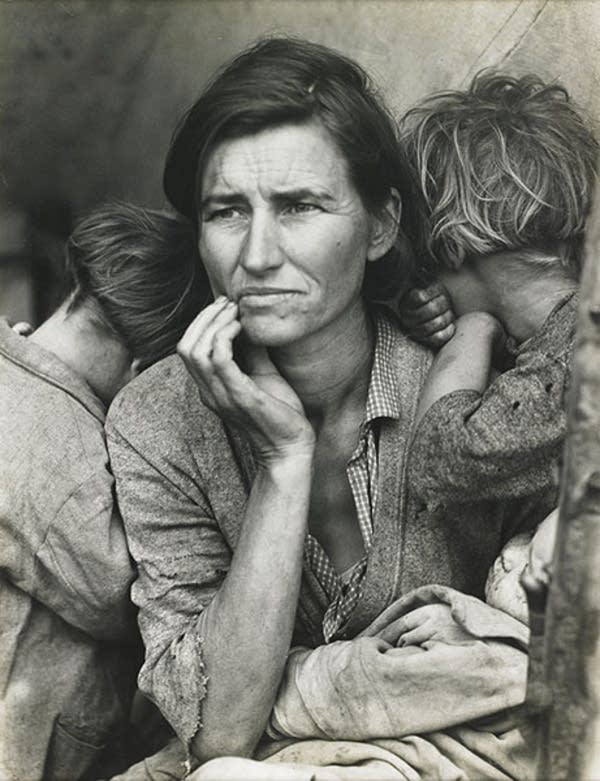

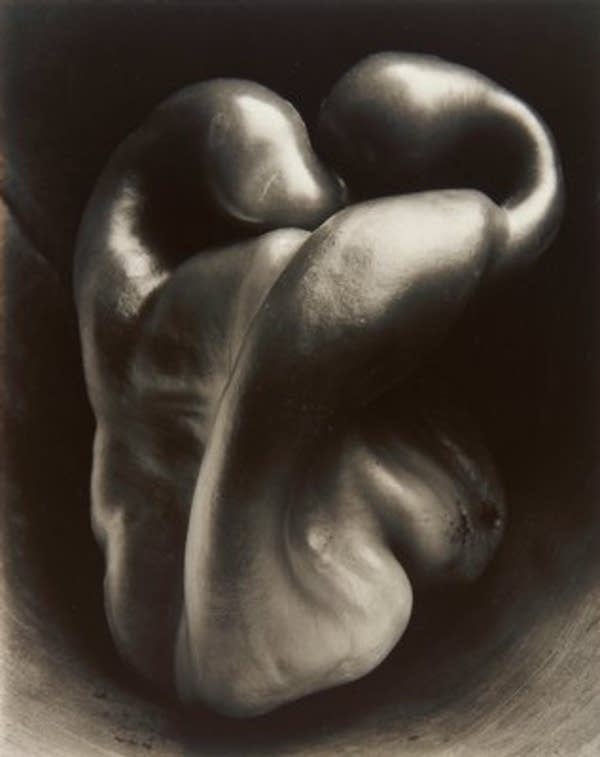

Today, the MIA's collection houses more than 10,000 photographs, including the works of such greats as Walker Evans, Edward Weston and Dorothea Lange.

In his early days at the museum, Hartwell had a reputation for being a bit of a bohemian, walking the halls with a Leica camera slung over his shoulder.

Photographer Stuart Klipper remembers an office filled with comfy furniture and an open-door policy that drew in all sorts of people for impassioned, philosophical conversations. Klipper says Hartwell took the time to truly examine his photographs and to teach Klipper about his own work.

"He probably could have gotten a job -- if he needed to -- as a dealer in a casino, because he moved photographs around to find juxtapositions and resonances and complementarities," Klipper recalls.

Klipper says Hartwell's passing marks the end of an era.

Another colleague, George Slade, artistic director of the Minnesota Center for Photography, says Hartwell will be remembered as a formalist and a bit of a romantic.

"Ted was a photographer who always talked about 'sweetness' in pictures, which is hardly a scientific or classically art-historical term." But, Slade says, "I think it reflected an interest in a very humane function of photography, that it tell stories, that it connect with our lives in some way."