Art Deco King: Remembering St. Paul artist Paul Manship on the 100th anniversary of a movement

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

A lion pounces, a centaur shoots an arrow and a ram floats in a cloud.

These are three of 12 large terracotta medallions representing the zodiac hanging at the Minnesota Museum of American Art (The M).

“They're one of the most popular things here,” says Tom Arneson, a volunteer at The M and a former interim director.

Each figure is rendered with lifelike detail, yet shaped with the clean lines and flowing curves typical of Art Deco design.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

The series was made in the 1960s, and are among the last of the artworks created by 20th-century artist Paul Manship.

“He was very interested in what is in the heavens. The celestial bodies and the signs of the zodiac fit into that, of course,” Arneson says.

Paul Manship, who grew up in St. Paul, became a major figure in Art Deco, the early 20th-century style marked by bold geometry, streamlined forms and decorative flair across everything from buildings to automobiles to sculpture.

This spring, Art Deco, celebrates its 100th anniversary.

The movement was named during the Exposition internationale des arts décoratifs et industriels modernes (International Exhibition of Modern Decorative and Industrial Arts) in Paris, which ran from April 29 to Nov. 8, 1925.

Manship, who often lived and worked in Paris during his career, was one of two American artists that exhibited at the exposition, says art historian Rebecca Reynolds.

“He was doing Art Deco before Art Deco had a name, as many artists were,” says Reynolds, who co-founded the Manship Artists Residency at the artist’s former summer home in Massachusetts.

Reynolds says Manship was recognized as a major force in the movement with the creation of “Prometheus” at Rockefeller Center.

In 1933, Manship led a team to fabricate the Greek titan who brought fire to mortals. Even at 18 feet long and eight tons, the sleek golden bronze figure appears to float effortlessly above the fountains.

“Rockefeller Center really is like the landmark of Art Deco in the United States, and Paul's piece was so prominently on display there,” Reynolds says. “It is one of the most photographed sculptures in the world.”

The Art Deco pioneer from Summit Avenue

Manship was born on Christmas Eve of 1885 in St. Paul.

He was one of seven children growing up in a house on Summit Avenue, and the family also had a summer cottage on White Bear Lake.

“My general boyhood was a very pleasant one, because, whereas my father was not wealthy, we lived in a nice house in town, and then lived in the summer at a nearby lake,” Manship recalled in a 1956 interview.

“The lake was 12 or 15 miles away, and there I spent the summers doing those things that a boy does. And it was in the ‘good old days,’ I assure you, before the turn of the century, when fishing was fishing and hunting was good.”

As a teen, from 1901 to 1903, Manship studied at the St. Paul Institute School of Art, now the Minnesota Museum of American Art.

“That was an important part of his development,” Reynolds says.

As a teen, he started his own art business in town, saved up money and moved to New York to study at the Art Students League. (Other Minnesota artists George Morrison and Wanda Gág also studied there.)

Manship would go on to study and work in Pennsylvania, Paris and London.

In 1909, he won the Prix de Rome scholarship to study for three years at the American Academy in Rome.

“Paul Manship was the youngest person at the time to receive that honor,” Reynolds says.

Sculpting the stars and myths of modernity

It was in Rome that he discovered ancient art from around the world, which helped shape the stylized, elegant forms that became his signature.

“So as a result of the inspiration that he had from archaic art — Greek and early Indian art and Asian art — he developed a style that was very stylized and simplified, but also very elegant.”

This can be seen in the lifesize 1926 sculpture “Indian Hunter and His Dog,” which was commissioned by 20th-century banker Thomas Cochran and is installed in a fountain at Cochran Park off Summit Avenue in St. Paul.

The bronze shows a Native American hunter in motion, bow drawn, with a leaping dog at his side. It’s stylized in Manship’s signature blend of classical form and Art Deco fluidity.

Manship cast the sculpture at the Alex Rudier Foundry in Paris, says Reynolds, “which was top of the line, just the most sophisticated foundry of the time.”

Reynolds says the “Indian Hunter and His Dog” was a favorite of the artist. It reminded him of his childhood in Minnesota.

The sculpture reflects the “Noble Savage” trope — a romanticized and harmful idea, popularized by 18th-century philosopher Jean-Jacques Rousseau, that idealizes Indigenous people as pure and primitive.

In 1932, Manship went on to craft the bronze gates to the Bronx Zoo, which feature all sorts of animals. He followed this with the Woodrow Wilson Memorial Celestial Sphere at the United Nations office in Geneva, Switzerland. It weighs six tons and shows 85 constellations — among his favorite themes.

Manship became enthralled with what he referred to as “astro-mythology” after visiting his first planetarium in Munich, Germany in 1931.

“The more I got into it, the less I knew, naturally. It was just a superficial and fragmentary sort of thing that fascinated me — that is, the treatment of the relationships of the constellations by the ancients,” Manship said in the 1956 interview. “So I began to draw the constellations as they had been handed down to us through the ages.”

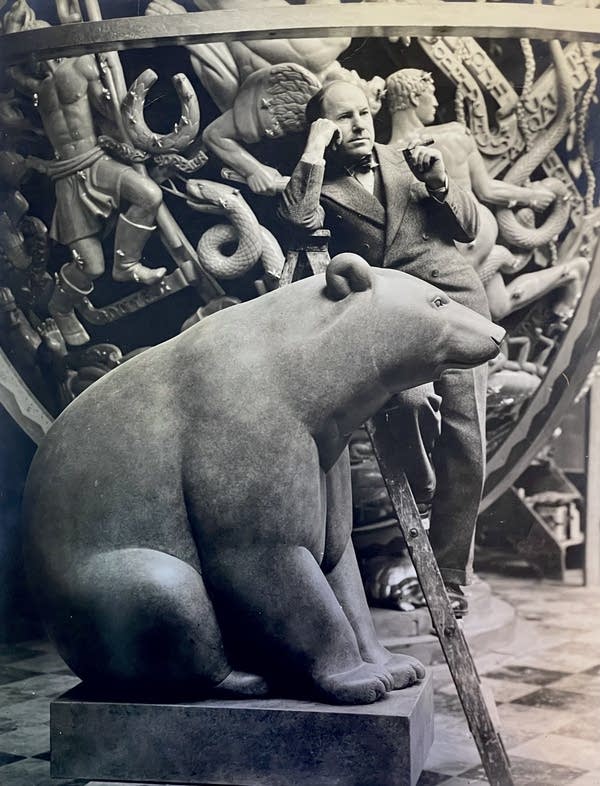

That fascination with mythology and form — combined with his technical skill— helped make Manship, known for his signature mustache and bowtie, one of the most successful artists of his time.

"Paul Manship is really recognized as one of the great technicians of creating sculpture,” Reynolds says.

“He had been intimately involved with the Smithsonian. He'd been on its board and Fine Arts Commission. He was one of the leaders in the art world at the time in the United States.”

Coming home to The M

Manship died at 80 in 1966 in New York.

Shortly before his death, Laurene Tibbetts, an assistant director at the Minnesota Museum of American Art, visited him.

Manship had planned to bequeath his collection to the Smithsonian American Art Museum in D.C. Tibbetts persuaded him to do otherwise.

“This very astute woman said, ‘Your foundation, your beginning, was here in St. Paul. You should bring some of that home,’” Reynolds explains. “So Paul Manship, two months before he died, changed his will, and he made it so that everything would be divided between St. Paul, the Minnesota Museum and the Smithsonian"

As a result, The M has hundreds of artworks by Manship in its collection.

Currently on view are the terracotta zodiacs, as well as a fierce pair of bronze birds, each life-size and standing on one leg, mounted in marble.

“These are wonderful,” Arneson says. ”These were modeled for the doors of the Bronx Zoo gates, one of his most famous commissions.”

The gilded birds are the epitome of Art Deco: streamlined, elegant, dramatic. The stork and a crane face off at the entrance of the museum’s New Wing.

Arneson says he thinks of them as guardians, watching over the place where Manship became an artist.