Trump's classified documents trial date is set. What to know about this complex case

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Former President Donald Trump's trial into his handling of classified documents is set for May 20, 2024. It's one of several criminal and civil cases Trump faces as he runs for president.

Trump, who has pleaded not guilty in the documents case, called it an "empty hoax."

The Justice Department wanted the trial to start in December; Trump's legal team wanted to push it past the 2024 election.

Daniel Richman, a law professor at Columbia Law School, said U.S. District Judge Aileen Cannon's order Friday setting a May 20, 2024, trial date was "an appropriate and reasonable effort to balance the legitimate needs of the defendants against the need to move the case forward as expeditiously as possible."

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

But the legal complexities involved, the quantity of classified evidence, and Cannon's lack of experience in such a case could contribute to lingering delays and headaches for prosecutors, Richman and other legal experts told NPR.

"[Cannon] doesn't have any experience in criminal cases involving classified information. She hasn't actually presided over a lengthy jury trial. They've all been short," Stephen Saltzburg, a George Washington University law school professor and former Justice Department official, said of Cannon's trial background. "On another hand, she might bring, as a younger judge, energy to this. But I think this is the kind of case where experience really does matter."

What are the specific charges against Trump?

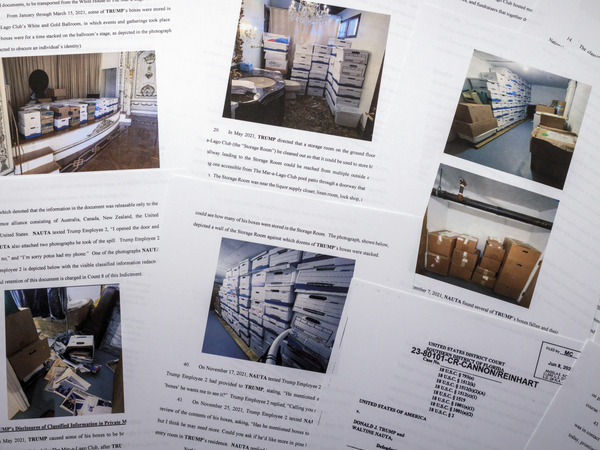

Trump faces 37 charges, including more than 30 violations of the Espionage Act, over allegations he stored dozens of classified documents at his Florida resort and refused to return them to the FBI and the National Archives.

He and his aide, Walt Nauta, are also charged with making false statements and conspiring to obstruct justice. Nauta's trial also starts on May 20.

The indictment alleges that Trump was personally involved in packing the classified documents as he left the White House in 2021, that he then bragged about having these secret materials and pushed his own lawyer to mislead the FBI about what he had stored at his Florida resort, Mar-a-Lago.

A trial date is set. That doesn't mean it will stick

Cannon cited the the extensive evidence presented in the case as one of the reasons she pushed the start date to next year.

This evidence includes "more than 1.1 million pages of non-classified discovery produced thus far (some unknown quantity of which is described by the Government as "non-content"), at least nine months of camera footage (with disputes about pertinent footage), at least 1,545 pages of classified discovery ready to be produced (with more to follow), plus additional content from electronic devices and other sources yet to be turned over," Cannon wrote in her order.

Trump and Nauta's teams have applied for a security clearance to go through the stacks of classified material ahead of the trial. This, alone could take weeks or even months to get approved — potentially pushing back Cannon's deadline even more, said Barbara McQuade, a professor of practice at the University of Michigan Law School and a former U.S. Attorney for the Eastern District of Michigan.

The attorneys will also be limited to where they can view these records. They won't be able to view the records at their offices or whenever they want to like in an ordinary trial, McQuade noted.

"They will probably be allowed to review the classified documents only in what's called a SCIF — a sensitive compartmented information facility — at the courthouse or at the FBI. They'll have to make appointments to come in and review all of these documents," she said.

Pulling relevant records to show to the jury is just the discovery phase, "which in most cases is a pretty straightforward process. But because of the classified nature of the evidence in this case, I think it could be a little more cumbersome and could cause more delay," she said.

Richman was more direct: There will undoubtedly be delays in this case.

"One general rule is that trial dates, in the early stages of a case, are often placeholders and don't mean anything. It's well understood that the date set will slip. That's true in all sorts of cases and I certainly expect it to be true in this case," said Richman, a former federal prosecutor in the U.S. Attorney's Office for the Southern District of New York.

This case will be tried under CIPA rules. What is that?

Trump's case will be tried within the rules of the Classified Information Procedures Act, or CIPA, a complicated statute that adds difficulties for the government's plans for a speedy trial, legal experts who spoke to NPR for this story said.

CIPA was passed by Congress in 1980 to control the disclosure of classified information in criminal prosecutions and to prevent something called "graymail." This is when a defendant threatens to release classified information, with the aim of forcing the government's hand to drop the case, Saltzburg said.

"The defense position is: Drop the case if you're not willing to make [classified documents] public," he said.

CIPA requires the defense to notify the court of any classified evidence they want to bring up in front of a jury and to submit it as part of the public record. A judge must then decide if this classified information is admissible. Under this federal law, the government can introduce an unclassified alternative that doesn't reflect any classified information.

"The first thing you're supposed to do is see whether you can come up with a substitute. And that is: A non-classified version of the same thing that will give the defendant a fair trial. And that's not always easy" and it can take a lot of time to come up with, Saltzburg said.

Submitting a summary of a classified document rather than showing the actual document is one option, he said. "But the defense may object to say it's not a fair picture. I'm sure there's going to be fights about it" in Trump's case, Saltzburg said.

Prosecuting cases with classified documents is hard. Just look at the Oliver North case

If an alternative can't be found, it's possible charges against Trump could be dropped, Saltzburg said.

This has happened before.

Saltzburg was part of the prosecutorial team in the criminal trial of Oliver North, who was involved in Iran-Contra affair during the 1980s.

"Everything got complicated because the North team wanted to show classified documents to the jury to suggest that he was doing what he was essentially ordered to do. And the intelligence agencies did not want those documents released," Saltzburg said.

That case faced lengthy delays. North went on trial for 12 criminal charges only after prosecutors dropped several charges against him.

A 1989 New York Times article on the opening day of the North trial said, "The case has been reduced somewhat in scope after the special prosecutor, Lawrence E. Walsh, dropped several important conspiracy charges against Mr. North because national secrets would have been disclosed in pressing them."

North was eventually convicted on three felony charges, but those convictions were later reversed and all charges dismissed in the '90s.

Given these difficulties with CIPA and classified records, Saltzburg and Alan B. Morrison, an associate dean at George Washington University Law School, wrote an op-ed saying they think prosecutors "should withdraw all but half a dozen" of Trump's 31 counts of wrongful possession of classified records.

"The fact that there were as many as 200 classified documents in unsecured locations at his home made the case more serious, but his refusals alone were sufficient reason to indict him," they wrote. "Focusing on his willful refusal to return the documents can shorten the trial and serve to undercut Trump's claim of selective prosecution— because no one else kept classified documents once the government asked for them back."

Saltzburg and Morrison argued that the 31 counts were useful to signal how serious the charges were, but would likely slow down the pretrial process "as Trump's lawyers will insist on examining each one of them and they will ask the judge for much more trial time so that they can be sure that each record was properly classified. The prosecution should attempt to see if a smaller document sample could be declassified."

Cannon's experience was questioned early on

Criminal cases involving classified documents are rare, Saltzburg said. "It's a very small percentage of the criminal cases that are brought throughout the entire United States. But there may be 10 or 15 of them," he said.

They usually come up in national security cases in Washington, D.C., and in the courts in the Eastern District of Virginia and the Southern District of New York, he said. "Lawyers in those jurisdictions have a lot of experience, so do a lot of the judges, and they know how to move these cases along," he said.

But Trump's case is being heard in a small courtroom in Fort Pierce, Fla., by a judge with no such background.

Cannon was appointed by Trump in 2020 and listed herself as a member of the conservative Federalist Society.

Her professional experience includes work as an assistant U.S. attorney for the U.S. Attorney's Office for the Southern District of Florida in Fort Pierce — the same city she works out of now as a federal judge, according to the questionnaire she filled out for her judicial nomination in 2020.

In 2013, Cannon prosecuted 41 cases out of the Major Crimes Division, according to the Associated Press. She later handled appeal cases for criminal convictions and sentences.

She also worked as an associated attorney at Gibson, Dunn and Crutcher in Washington, D.C., a summer associate at Squire Sanders (now known as Squire Patton Boggs) in Miami and served in a short stint with the Justice Department's Civil Rights Division as a paralegal specialist.

But it's those ties to Trump as one of his appointees that has raised concern, and questions, over whether Cannon can serve as an unbiased judge in this case.

There were calls for Cannon to recuse herself almost immediately after she was assigned the case. But her background is pretty standard, according to Richman.

"She was in the system for quite some time, she came out of a well-respected firm, she got her name pushed forward by her local senator. And yes, she's got a Federalist background, but so do quite a few other judges," Richman said.

McQuade said, "I think the fact that she's been appointed by Trump is not relevant. We accept the notion in this country that judges get appointed by presidents of both parties and that when they take the bench they are supposed to be independent. That's why they're appointed for life."

McQuade said as for Cannon's perceived lack of experience: "Every judge is new at some point. Judges are randomly assigned [cases] and some are new and that's just the way it goes. Over time she will become experienced."

Cannon's early actions in this case rightfully raised some red flags, lawyers say

Cannon is the same judge who ruled in favor of Trump's request to appoint a special master to review documents seized by the FBI from Mar-a-Lago last summer. This temporarily prevented federal prosecutors from continuing their investigation into the former president's possession of classified documents. Cannon also ruled to unseal a list of items the FBI seized from their search of Trump's home.

This ruling sparked serious pushback from the Justice Department and some in the legal community who questioned Cannon's legal rationale in that decision.

And it's criticism and serious concerns that Saltzburg, McQuade and Richman shared.

"I think people are concerned about her mostly because of the way she ruled in that search warrant matter, which was, to me really obviously wrong," McQuade said.

Cannon's decision to request that special master was reversed by the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Eleventh Circuit.

Saltzburg said his feelings on Cannon changed when on Friday she pushed the start date of the classified documents trial until May 2024 and issued a detailed schedule of hearings for both sides to adhere to.

"This is just what I would expect from a judge who had experience in classified information cases," he said. "It is impressive and shows considerable thought. If Judge Cannon sticks by the schedule, she will have demonstrated an ability to control a complicated case."

Copyright 2023 NPR. To see more, visit https://www.npr.org.