College students uncover history of racist housing deeds in Stearns County

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Updated: 9:38 a.m.

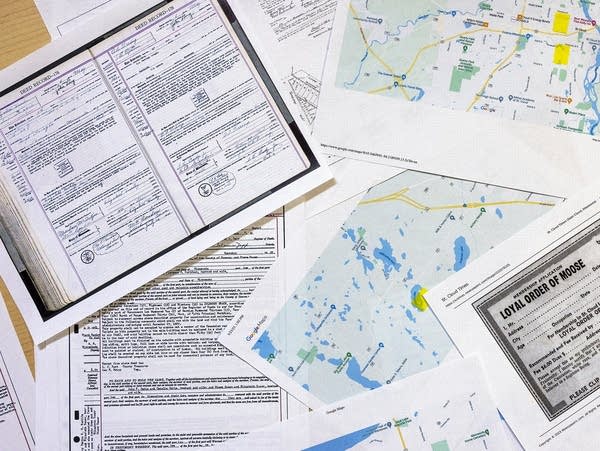

Professor Brittany Merritt Nash's honors history students at the College of St. Benedict and St. John’s University were familiar with racial covenants — clauses inserted into property deeds that reserved homes and land exclusively for white people, or prohibited them from being sold to certain ethnic groups, including Jews.

But most research on restrictive covenants has focused on the Twin Cities metro. The students wondered whether the same thing happened in central Minnesota, and decided to launch their own research in Stearns County.

Halfway through the semester, they'd uncovered 95 racial covenants in St. Cloud, St. Joseph, Cold Spring and Sauk Centre — proving that attempts to prevent people of color from owning property extended well beyond the Twin Cities.

“I think that all of us found it really remarkable how many there were,” Nash said.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

‘Measure of security’

St. Cloud had about 20,000 residents in the 1920s and very few people of color.

But that didn't stop housing developers from writing restrictions aimed at keeping out anyone who wasn't Caucasian, said Christopher P. Lehman, an ethnic studies professor at St. Cloud State University and author of the book, “Slavery’s Reach: Southern Slaveholders in the North Star State.”

“I suppose with these restrictive covenants came a measure of security that these all white places were just going to stay all white for a long time,” Lehman said.

While researching Stearns County’s property records for historic evidence of slavery in Minnesota, Lehman discovered much more recent examples of discrimination.

“So instead of finding real estate deeds related to slavery in the 1850s, I was finding restrictive covenants related to the 1950s,” he said.

Standard discriminatory language

After reading about Lehman’s work, the students at St. Ben's and St. John's decided to expand on it. They spent hours combing through Stearns County's digitized property record and found startling results.

For example, a covenant from what is now St. Cloud’s Centennial Park neighborhood includes this clause: “No person or persons other than of the Caucasian race shall be permitted to occupy said premises or any part thereof."

The students say builders often added standard discriminatory language to deeds for all homes in a new development.

The covenants might not have actively kept out people of color, because there were so few of them. But the practice still had lasting impacts on social, cultural and economic life, Merritt Nash said.

“It still created in general the sense that St. Cloud and central Minnesota are restrictive communities, in which people of color aren't welcome,” she said.

Lingering impacts

Racial covenants didn't just exclude people from owning a home, but also from the perks of living in a neighborhood — including access to parks, schools and businesses, Lehman said.

“By not being able to buy homes in that area, you don't have property that you can pass down to your kids,” he said. “So the important intergenerational wealth is missing from the families of those who are excluded from those neighborhoods.”

The students say their findings counter the notion that racism was absent or less of an influencing factor in northern states such as Minnesota. Rather, it was silently ingrained in many systems, including home ownership, said Robert Smith, a junior biology major.

“It's important to spread awareness that this did have an effect on many people's lives, and it continues to ripple into today,” Smith said.

Racial covenants became illegal in Minnesota in 1953, but some were drafted well after that. Nash's students found one deed signed in 1981.

Patterns of discrimination

The number of racial covenants the students uncovered in Stearns County doesn't surprise Kirsten Delegard, co-founder of the Mapping Prejudice Project at the University of Minnesota. It’s uncovered about 30,000 similar documents in Hennepin and Ramsey counties so far.

“We know that racial covenants are pretty much in every county across the country,” Delegard said. “There's no place that people have gone looking for them where they have not found them.”

Delegard said powerful organizations with extensive reach promoted the use of racial covenants. That included the National Association of Realtors and the federal government, which made racial covenants a condition of favorable loan rates in the 1930s.

She said people often mistakenly think of racial covenants as a reaction to the migration of Black people from the rural South to the urban North.

“One of the things that is illuminating about looking at Minnesota is finding that that pattern just doesn't hold true — that it's a preemptive effort here to make sure that all the land is reserved for white people,” Delegard said.

While racial covenants are no longer enforceable, Nash said the students want to continue studying lingering racial divides in real estate — including white flight to suburbs such as Sartell, Sauk Rapids and Cold Spring as St. Cloud’s population has gotten more diverse.

“Even though the deeds aren't valid anymore, the attitudes and the understandings continue to linger,” she said.

Seeking change

Some greater Minnesota cities including Rochester and Mankato have launched efforts to track and remove racial covenants, many through the Just Deeds coalition.

No organized effort is underway yet in Stearns County, but the students say they're sharing their research with the county history museum to raise awareness.

Stearns County Recorder Rita Lodermeier said the county board hasn’t taken any formal action on the issue, but her office has reached out to the Just Deeds project.

“I think it’s important to get this out there, so people can get these restrictions removed from the records,” she said.

Under Minnesota law, property owners who discover racist language on their deed can fill out a form with their county recorder’s office discharging the restrictive covenant.

It’s largely a symbolic move, Delegard said, and should be people’s first step toward making their neighborhood more equitable.

“What can you do then to increase homeownership opportunities for people who are not white?” Delegard asked.