Xcel: Radioactive water leaked in November at Monticello nuclear plant

Officials say cleanup continues and they're monitoring local wells

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Updated: March 16, 10 p.m.

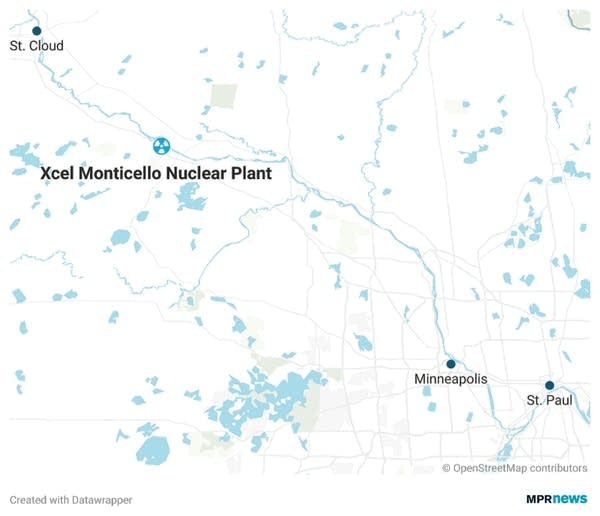

Water containing tritium, a radioactive form of hydrogen, leaked out of Xcel Energy's nuclear power plant in Monticello, Minn. in November, state officials said Thursday.

Xcel reported that about 400,000 gallons of the tritiated water leaked from a water pipe between two buildings.

State officials said the tritium was found during routine checks of ground water.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

“The leak has been stopped and has not reached the Mississippi River or contaminated drinking water sources. There is no evidence at this time to indicate a risk to any drinking water wells in the vicinity of the plant,” the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency said in a statement.

How did the leak start?

Xcel reported the leak to government regulators on Nov. 22, the day it was confirmed, but Xcel Energy Regional President Chris Clark said it's unclear when the problem began.

"As we do a full root cause analysis, we'll have a better understanding of whether that was a few days, a few weeks, a month. But we just don't know that at this point," Clark said.

Clark said workers have pumped about 25 percent of the tritiated water out of the ground and are treating it on site. He said it’ll take about a year to remove the rest.

The steel pipe that leaked is about four inches in diameter and carries condensate water away from the steam turbine that drives the plant’s generators. Pat Flowers, Xcel’s manager of environmental services said the damaged pipe was in an inaccessible spot.

“The leak took place in that tiny little space and it wasn’t really visible until you drilled a hole through two feet of concrete to get to it to physically see what was leaking,” Flowers said.

Xcel will analyze the pipe to try to find out what caused it to break, Flowers said.

"In order to really understand what happened to this pipe, we're going to have to take out several feet of concrete around the pipe so that we can get access to it,” Flowers said. “That's not going to happen until our [routine refueling] outage that starts here in mid-April, and we've got plans in April to remove that pipe so we can do the metallurgy, we can repair it, and we can also understand what took place, what caused the failure."

Though both state and federal regulators knew about the leak around the time Xcel staff discovered it, state officials did not inform the public about it for nearly four months.

The NRC’s November public notice was not in a news release, though it can be seen online at the bottom of a list of “non-emergency” event notification reports.

Both state and company officials said they did not notify the public when the incident occurred because the tritiated water was not moving toward toward drinking water wells and did not pose a danger to people near the plant.

“If at any time, we had felt that there was any threat to Minnesotans, their health or their safety, we would have notified people immediately,” said assistant Minnesota Health Commissioner Dan Huff.

The company said it is monitoring the groundwater plume at two dozen wells, and is considering options to dispose of the collected tritium. Minnesota regulators will review those options, MPCA said.

How dangerous is tritium?

Tritium occurs naturally in the atmosphere. But it’s also produced through fission in nuclear reactors. Because it’s a type of hydrogen, it reacts with oxygen to produce radioactive water.

Tritium is hazardous but only if ingested in large concentrations. The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency said tritium emits beta particles at such a low level that they are unable to penetrate human skin.

“While tritium is radioactive, it’s low energy, and so it’s not like plutonium. If you were to sit it next to you in a glass, it wouldn’t hurt you,” Huff said. “If you drank it, it would increase your radiation exposure. And we want to limit radiation exposure because radiation can cause tissue damage.”

Brian Vetter leads the Department of Radiation Safety at the University of Minnesota, where he oversees nuclear materials in the U’s research labs and medical facilities. He doesn’t work for Xcel or its government regulators.

“We’re drinking extremely small quantities of radioactive water all the time: radium, tritium,” Vetter said. “It’s just a part of our naturally radioactive world that we all live in. Very extremely small quantities, but you want to keep them extremely small.”

Both the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency and Xcel said testing indicates that the underground plume of contaminated water has not spread outside plant boundaries.

The MPCA says the closest public well is less than a mile from the plant, but is on higher ground, so the tritiated water isn’t flowing to it.

There’s also a potable water well on the Monticello plant property that employees use. Chris Clark, the Xcel executive, said there’s no evidence of tritium in that particular well, and he said he would drink from it.

“I’d be happy to drink that water. I’ve actually drank that water there at the plant,” Clark said. Our employees are there and of course we care about our employees, we care about our community. Our employees live in the community of Monticello and communities around there.”

MPCA assistant commissioner Kirk Koudelka said the agency is overseeing Xcel’s cleanup efforts.

“We are monitoring the area. Xcel is taking actions to remove contaminated groundwater from one series of wells, and in addition using other wells to control the contamination to prevent it from going offsite, whether that’s the river or outside its property boundaries,” Koudelka said.

The leak report comes as Xcel is asking federal regulators to extend Monticello’s operating license through 2050 — when the plant will be nearly 80 years old.