Indigenous communities see rise in COVID-19 cases

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

When vaccines for COVID-19 first became available early this year, Minnesota's tribal communities were quick to make them available to their members. One of the first to get vaccinated was White Earth chair Michael Fairbanks.

He’s 58 and in pretty good health, so he was surprised last week when he tested positive for COVID-19. He got the news at a tough time. Three of his friends from the Leech Lake Band of Ojibwe had recently passed away from complications of COVID.

"It scared me, you know, put a shockwave through my whole body that, dang, you know, I don't want to get sick like they did and end up heading out, you know," Fairbanks said.

He only had minor symptoms — a cough and some aches and congestion. Still, he wanted to share his experience with other band members. So Fairbanks wrote a message on Facebook, urging people to remain cautious. He admitted he should have been more diligent about wearing a mask indoors with family and friends.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

"That's what I said, because when you get the vaccination — both shots — it kind of puts like a mindset in you, like you're untouchable, you know?" Fairbanks said.

Fairbanks believes case numbers are rising in Indian Country because after months of following public health recommendations to mask, socially distance and avoid crowds, people have let their guard down.

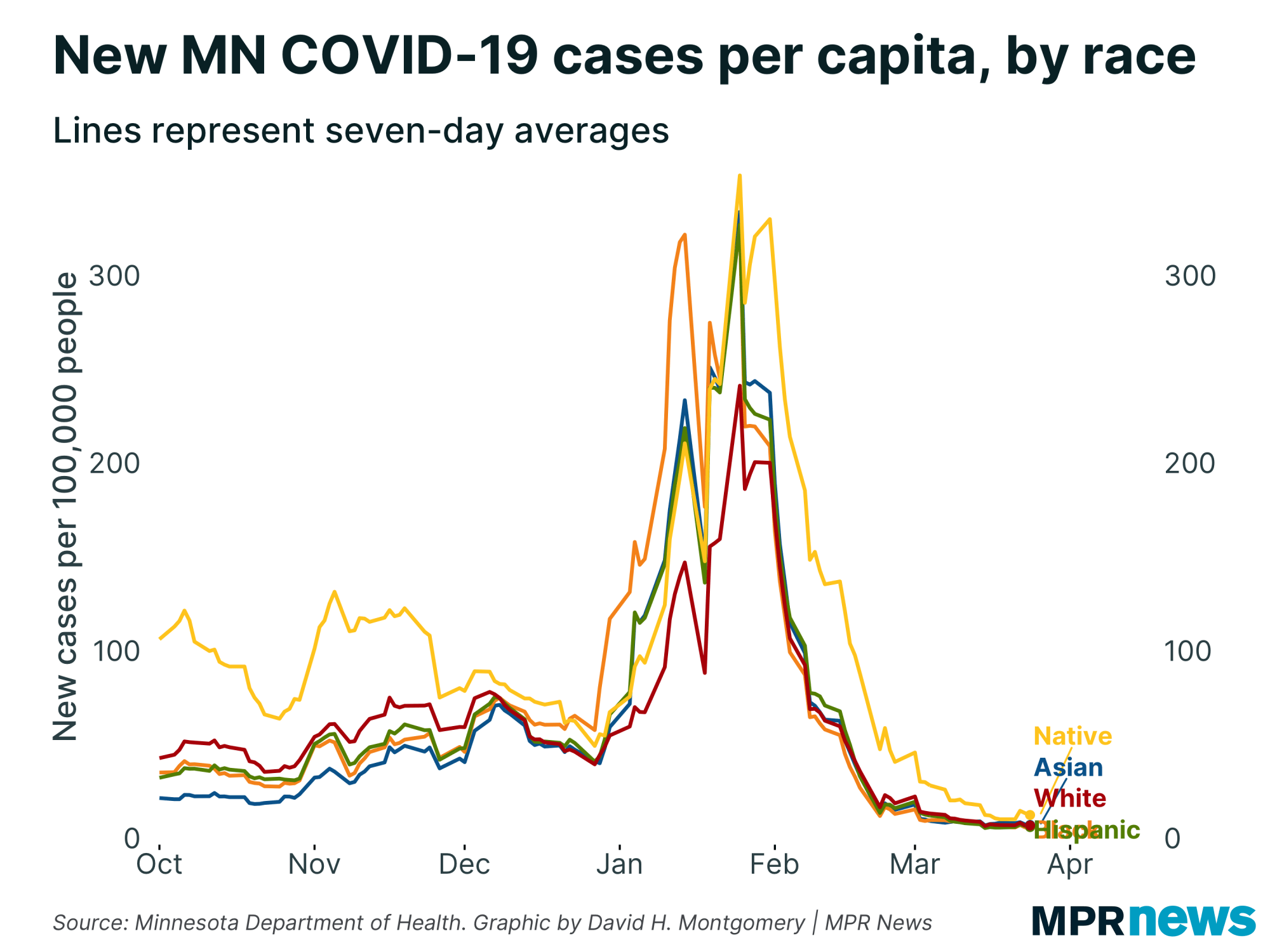

Over the past month, Native Americans have contracted COVID-19 at two to three times the rate of white Minnesotans, according to the Minnesota Department of Health.

The Leech Lake reservation has recorded its highest numbers of positive COVID-19 cases over the past month since the pandemic began.

And after having hardly any COVID-19 on the reservation throughout most of the summer, cases at White Earth started to rise in August and peaked in late September.

"It's certainly been a busy couple months here lately on the White Earth reservation," said Ed Snetsinger, emergency manager for the White Earth Nation, who also attributes the spike in cases to people not being as careful about wearing masks or social distancing.

Snetsinger said while there have been breakthrough cases like Fairbanks, for the most part it's the unvaccinated who are giving the virus a foothold to spread.

The reservation is at about 60 percent vaccinated among those who are eligible, Snetsinger said — about the same as the statewide rate for Native Americans. That's a higher rate than Black Minnesotans, but lower than Asian, Hispanic and white Minnesotans.

And White Earth and other tribes face some of the same barriers as elsewhere in convincing people to get vaccinated, Snetsinger said.

"I think there's a lot of misinformation out there that deters folks from receiving vaccines [and] for wanting to receive a vaccine,” Snetsinger said. “So it's definitely a challenge."

Snetsinger also notes that tribal communities have a large younger population that's not eligible to get vaccinated yet. He hopes that once vaccines are approved for 5- through 11-year-olds, the virus will have a harder time spreading.

In tribal communities in Minnesota and across the country, there are large pockets of unvaccinated people in the 18 to 49 age range, said Mary Owen, Director of the Center for American Indian and Minority Health at the University of Minnesota Medical School.

"We have some folks who are not getting vaccinated, whether it's because they're resisting it or because they're not able to get access. Not quite sure. It's probably a combination of those. But that's impacting us again, significantly," said Owen, who is also president of the Association of American Indian Physicians.

Owen says that's especially concerning because Native Americans have high rates of diabetes and other diseases — health disparities that put them at higher risk for serious COVID-19 illness.

"We have some very frail people in our communities that cannot afford to get infected. We have to protect them,” Owen said. “So please, do what's right for our communities, not just for us as individuals."