‘Forever chemicals’ found in groundwater at dozens of Minn. landfills

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

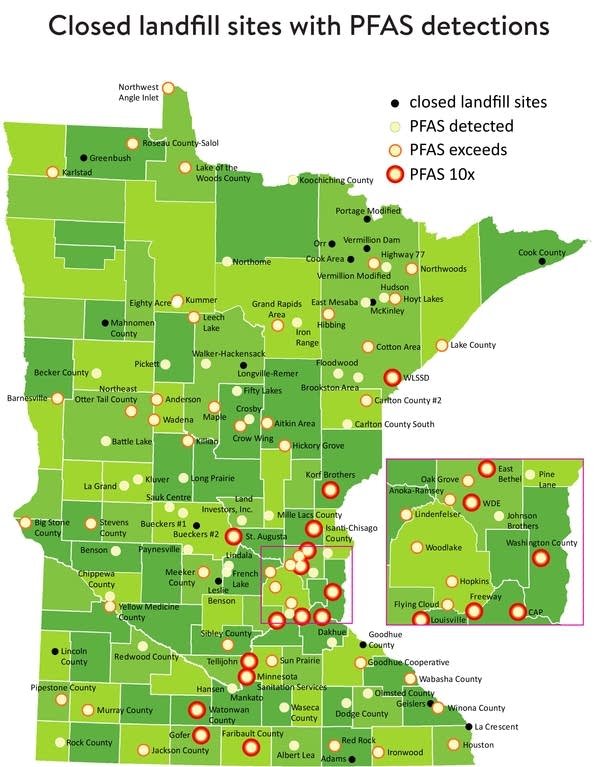

The Minnesota Pollution Control Agency says contamination from PFAS — so-called “forever chemicals” — has been detected in groundwater at nearly 60 closed landfills, at amounts higher than the state’s acceptable levels for safe drinking water.

Fifteen of the closed, mostly unlined landfills have PFAS contamination at least 10 times higher than the state’s health-based advisory values. One — Gofer Landfill near Fairmont in Martin County — is more than 1,300 times higher.

The findings highlight the ubiquitous nature of PFAS, or per- and poly-fluoroalkyl substances, a large class of man-made chemicals. They are found in a wide variety of products, including nonstick cookware, waterproof clothing, carpet, food packaging and firefighting foam.

Known for their durability, PFAS don’t break down easily and tend to accumulate in the environment, humans and wildlife. Some PFAS have been linked to negative health impacts including low birth weight, kidney and thyroid problems and some cancers.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

Most of the focus on PFAS in Minnesota’s drinking water has focused on the east Twin Cities metro area, where chemicals produced for decades by 3M contaminated the water supply of about 140,000 residents. 3M agreed to pay $850 million to settle legal claims filed by the state attorney general.

However, the latest finding is part of a growing body of evidence that the PFAS problem is much more widespread than previously thought.

“These closed landfills are throughout the state,” MPCA Commissioner Laura Bishop said. “They are in suburbs, greater Minnesota regional centers and small rural communities. They are next to our homes, our businesses and our farms.”

The MPCA said in total, it found PFAS contamination at nearly all — 98 of 101 — closed landfills it tested. The 59 landfills with PFAS levels higher than the safe drinking limits are located in 41 different counties, stretching from the Northwest Angle nearly to the Iowa border.

The 15 with the highest levels are located across the state — in Martin, Dakota, Washington, Anoka, Isanti, Stearns, Scott, Faribault, Watonwan, Le Sueur, Pine, and St. Louis counties. The chemicals found at those sites were PFOA and PFOS, the two most well-known PFAS compounds, which are no longer manufactured in the United States.

Groundwater provides drinking water for about three-fourths of Minnesotans. State health officials set the health-based values to indicate what level of chemicals it considers safe for people to drink over their entire lifetime.

Gofer Landfill, north of Fairmont in Martin County, closed in 1986. The MPCA said multiple PFAS were detected in groundwater at concentrations 1,343 times the health risk limit at that landfill. The agency said it tested all drinking water wells within a mile of the landfill and did not find any PFAS, and the city of Fairmont’s source of drinking water — Budd Lake — is not affected.

At Louisville Landfill near Shakopee, seven of 12 active groundwater monitoring wells indicated high PFAS levels. An underground fire also started at the landfill in late 2020.

The landfill, located near the Minnesota River in Scott County, closed in 1990. The MPCA plans to test the river, Gifford Lake and nearby residential wells.

MPCA officials say the agency will expand water monitoring and testing efforts to get a better idea of the scope of the contamination and if further action is needed, such as providing residents whose wells are affected with bottled water. They also said more study is needed of active landfills, which were not part of the closed landfill monitoring.

Last month, state officials outlined a broad “blueprint” to address PFAS pollution, including designating them as hazardous substances under Minnesota’s Superfund law. State regulators say that would make it easier for the state to hold companies financially liable for cleaning up PFAS pollution.

That proposal and several other PFAS-related bills are under consideration at the Legislature.

The blueprint also calls for additional state funding — about $3 million over the next two years — for researchers to identify sources of PFAS in the environment, including how the chemicals are coming into landfills, compost sites and wastewater treatment plants — and ending up in Minnesota’s waters.

The MPCA also requested the ability to use funds from a closed landfill program to address unexpected environmental releases, rather than waiting for the Legislature to approve funding.

Deanna White, state director of the nonprofit Clean Water Action, said the latest discovery isn’t surprising given that products containing PFAS have been used and discarded for years.

“Unfortunately, the chemicals don't break down,” White said. “So this is just further proof that PFAS contamination is not just an east metro problem or a problem for communities that are close to airports, or even just for communities with landfills with closed landfills. Wherever we test for PFAS, we will likely find it.”