Picture book deals head-on with the loss of a child

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

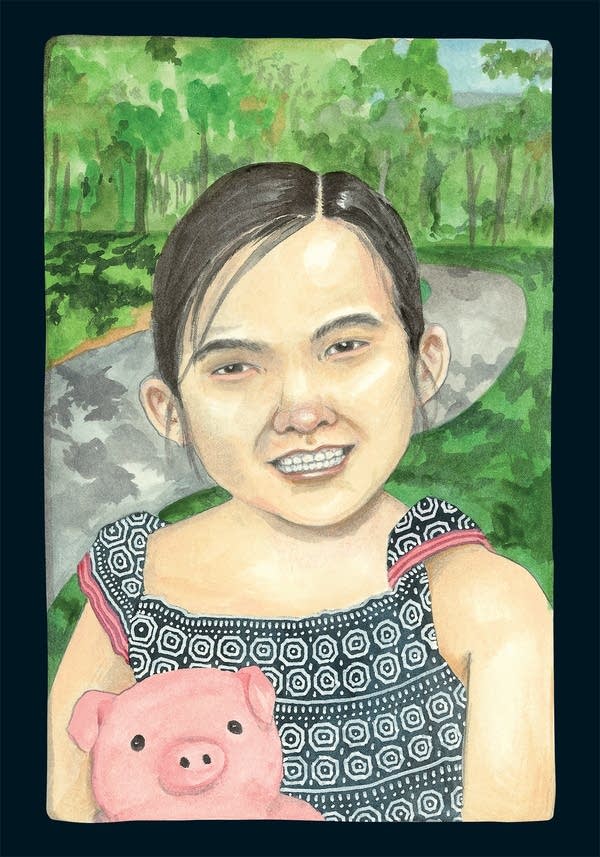

"The Shared Room," is award-winning writer Kao Kalia Yang’s response to a recent local tragedy: the 2017 drowning of 6-year-old Ghia Nah.

Ghia was no stranger to Yang. She and her family attended Yang’s readings.

“She often told me that when she grew up, she wanted to be a writer," said Yang, who, like Ghia, is Hmong. "Not just any writer, but a writer like me."

Born in a refugee camp in Thailand, Yang came to the United States at age 6. She wrote the award winning memoirs, "The Late Homecomer" and "The Song Poet," about her family's experiences. She published her first picture book "A Map into the World" last year. It's based on her family's friendship with an elderly neighbor whose wife had died.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

So, she was no stranger to telling personal stories. But dealing with the loss of a child, a sibling, is tough. And that's why Yang wanted to write a book for young readers.

“The death of other children is not a subject that many picture books go into," she said. "I grew up in a home where many, many women have lost children. And so, it was what I could do to honor Ghia Nah's life but also the grieving process that her family was undergoing."

Yang wrote a first draft, based partly on details from the family's social media account. Then she arranged to meet Ghia's parents to get their approval. They sat together in a neighborhood coffee shop, where they read it.

"And then they both wept,” said Yang. “They said that the hardest thing was that nobody wanted to talk about her. Nobody knew how to speak about her. And they were just so grateful that I had used her name, Ghia Nah."

Yang went ahead, approaching another Hmong American, artist Xee Reiter, to create the pictures. Reiter was already a fan.

"When I started to read her writing, it was just amazing. It just brings me to tears every time," Reiter said. 'When she approached me on Facebook, I was thrilled."

Despite both living on St Paul's east side, they had never met.

But Yang said she wanted an illustrator who was Hmong and could capture their part of town.

"Xee is also a mother. And so I knew that she would feel the story as deeply as I do," Yang said.

"The Shared Room" is straightforward and powerful. It tells the story of a family whose eldest daughter drowned. Her parents and siblings feel lost, disconnected by sadness. Reiter's paintings are evocative and some are filled with raw grief.

"This book is so emotionally charged," Reiter said. "There were often times that I would sit at the table before I started working and I would just cry reading it."

A pivotal moment in the book comes directly from Ghia Nah's story. The oldest son tries to remain strong. But when his parents ask if he would like to move into his sister’s room, the boy finally breaks down and weeps. This cathartic moment helps everyone move on.

The book was written before the pandemic. Virus precautions canceled most publication events. Yang said the launch has been the quietest for one of her books, but perhaps the most important in a country she describes as “grief-averse.”

"We as a nation are grieving right now," she said. "And so many of us are grieving alone in our homes. And so it's particularly challenging."

When she got her first copies of "The Shared Room," Yang took one round to Ghia’s family.

She found them in the yard, planting flowers in her memory.

Yang said she knew because of COVID-19 she should put the book down so Ghia’s mother could pick it up. But that felt wrong.

"I handed it to her with my hands outstretched, and she took it," Yang said. "And then she put it against her heart. She held the book against her heart. We stood there in that moment together. Then we said to each other 'When this is all over, we will give each other big hugs.’ ”

Embraces that rise from a deep well of grief, with the strength to go on.