Minnesota is an 'incubator' of presidential ambition but not presidents

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Let's face it: Minnesota has a poor track record when it comes to presidential hopefuls.

Democratic Sen. Amy Klobuchar's entry into the 2020 presidential race puts her in the company of Minnesota political figures to go after the nation's top job.

In the last century, six politicians who made their name here took a serious shot at the White House.

"It is an incubator of ambition," said James Thurber, a distinguished presidential scholar at American University.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

A couple of the Minnesotans got tantalizingly close to occupying the Oval Office. But all met the same fate: A loss.

Minnesota is far from alone in lacking claim to a president born or politically raised inside its borders. Exactly half the states are in the same boat.

The trail of disappointment starts in 1948 with former Minnesota Gov. Harold E. Stassen.

Stassen was Minnesota's "boy governor" elected at age 31. He gave up the office to join the Navy and go to war. Upon his return, he became a prominent national voice on foreign affairs. He sought the presidency 10 times, turning him into something of a punchline.

But he was a legitimate Republican contender early on. Stassen came up just shy of the party's nomination in that 1948 initial run and got a hard look again four years later.

Stassen reflected on his pursuit in a 1986 MPR interview.

"My philosophy has been what I call the 'creative center,'" Stassen said when at the time he was running for Congress, a race he lost. "I never have been on either of the extreme of the conservative or liberal side of the right or the left."

The 1952 race was also when then-Minnesota Sen. Hubert Humphrey made his initial attempt at the presidency. His Democratic Party bypassed him in and put his presidential ambition on hold. He fell short in the 1960 race, too.

The next Minnesotan to step forward was Sen. Eugene McCarthy. He set out in 1967 to pressure fellow Democrat and incumbent President Lyndon Johnson over the Vietnam War. But McCarthy found himself in deeper.

"Inherent in the process once it had begun and I knew that I might very well become a presidential candidate, which I have," McCarthy said in 1968, explaining how a run for president wasn't the main objective at the outset.

McCarthy's near-upset over Johnson in the New Hampshire primary was among the factors that led to the president's surprise announcement weeks later that he wouldn't try for another term.

Johnson's vice president stepped into the void. That, of course, was Humphrey.

This time in an abbreviated race — Humphrey didn't declare until April 1968 — he did land the nod. The Democratic Party ultimately picked Humphrey over McCarthy and a few others. But fractures over the war in Vietnam and an ugly nominating convention lingered through his general election campaign with Republican Richard Nixon.

In defeat, Humphrey called for national unity.

"I have done my best. I have lost. Mr. Nixon has won," he told supporters in a concession speech. "The Democratic process has worked its will. So now let us get on the with urgent task of uniting our country."

In terms of vote share, Humphrey wound up closer than any Minnesotan to becoming president. He returned to the Senate a couple of years later, taking the place of McCarthy who decided against a re-election run.

Humphrey wasn't the last Minnesota figure to have a real chance.

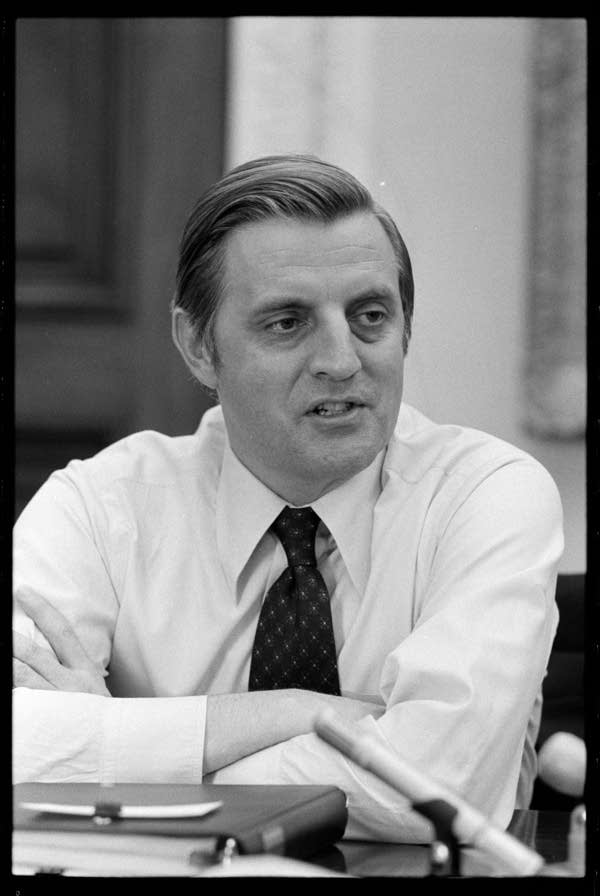

A few years after his own stint as vice president, Walter Mondale came to Minnesota's Capitol in 1983 to launch his presidential campaign.

"I do not begin this journey alone today," Mondale said in that launch. "I begin it here with you, my friends who started me out in public life and who've sustained me all of these years."

The former Minnesota senator was the Democratic front-runner and would ultimately land the nomination. But he ran into a buzzsaw in Republican President Ronald Reagan, who won all but Minnesota in a historic landslide reelection.

"Modern politics today requires mastery of television. I think you know I've never really warmed up to television," Mondale said a day after his defeat. "And in fairness to television, it's never really warmed up to me."

Professor Thurber agreed the demeanor of Minnesota candidates has at times held them back.

"Certainly the mild nature and civility of Minnesotans is well known," Thurber said. "It doesn't cut through the media, especially the television media."

He added that heartland candidates often struggle for the kind of attention those from the coasts receive and to raise oodles of money that's so crucial in modern campaigns.

The two most recent candidates, both Republicans, saw their hopes dashed early in part because their funds dried up.

Former Minnesota Gov. Tim Pawlenty was viewed as a top prospect heading into the 2012 campaign. He kicked off his campaign in Iowa, playing up his Midwest connection.

"Now I'm not some out-of-touch politician from some other part of the country. I served two terms as governor of an agricultural state," Pawlenty said, adding for emphasis, "I'm not from Washington. I grew up in Minnesota."

He failed to gain traction and was out a few months later.

The charismatic U.S. Rep. Michele Bachmann, a favorite of the tea party movement that was fueling GOP enthusiasm at that time, also banked on Iowa to catapult her campaign. "I'm a descendent of generations of Iowans. I know what it means to be from Iowa. I know what we value here. I know what's important," she said at her campaign kickoff in her birth city of Waterloo.

"I've often said everything I need to know I learned in Iowa," Bachmann told supporters there.

Bachmann held on longer than Pawlenty but exited after a disappointing finish in the leadoff Iowa caucuses in January 2012.

Klobuchar put her campaign in motion during a snowy rally Sunday along the Mississippi River. She rhetorically traced the river's path from its origin in Minnesota through a region that has become political swing turf in presidential contests.

"And then down to Iowa, a place where we in Minnesota like to go south for the winter. At least I do," she said.

Klobuchar went on, "And then to Illinois, a state that boasts a lot of extraordinary presidents, from Abraham Lincoln to Barack Obama."

The comparable Minnesota list, as of now, remains empty.