Pipeline plan tests state's environmental-business balance

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Every day for nearly 70 years, a river of oil has flowed silently underground across the northern third of Minnesota to oil refineries across the Midwest and Gulf Coast that turn it into gasoline, jet fuel, propane and other products that millions of Americans rely on.

The oil — about 2.5 million barrels daily — flows from western Canada through six pipelines operated by Calgary-based Enbridge Energy. At 4,100 miles long, it's the world's longest oil pipeline system, five times longer than the Trans-Alaska pipeline.

Minnesota regulators are weighing now whether to let Enbridge add to that network. Enbridge wants to replace its aging Line 3 pipeline with one that could carry about twice as much oil along a new route across the state. Standing in its way: Ojibwe tribes and environmentalists who argue Minnesota is inviting disaster by backing another high-volume oil pipeline from a company with a checkered past safety record.

The Minnesota Public Utilities Commission is expected to decide in June whether to grant Enbridge the certificate of need and route permits required to begin construction. Commissioners will have to answer the question: Does Minnesota need Line 3? And if it does, are the benefits worth the risk of routing it through the lakes and rivers of northern Minnesota?

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

It's a complex decision that will test Minnesota's ability to balance the demands of industry and the environment. The $7.5 billion project would deliver new tax revenue to the state and an economic jolt to the towns along its path. But the potential for an environmental crisis hangs in the air, and the state's Commerce Department has concluded that Minnesota really doesn't need the extra oil.

How does the state measure the potential economic gains of a new Line 3 against the possible risks to the Minnesota lakes and rivers near its path? Is it worth the ire of Minnesota's northern Ojibwe tribes, which fervently oppose the flow of oil across their reservations and across the land they ceded to the state in treaties long ago?

Enbridge's case for the pipeline

The current Line 3 is corroded and cracked, the company says, resulting in nearly 1,000 excavations and repairs the past 16 years. Since 1990, the line has leaked or spilled at least 50 barrels of oil on 15 different occasions — seven times in Minnesota, including the largest inland oil spill ever in the U.S., in 1991, outside Grand Rapids, Minn.

To keep the old line safe, the company has dropped pressure in the pipe and reduced the amount of oil it transports. To keep it running safely, the company projects it would need to perform 4,000 so-called "integrity digs" on the U.S. part of the line over the next 15 years at a cost of $30 to $40 million per year.

"This is a 1960s-era pipeline," said Enbridge spokesperson Jennifer Smith. "The best way to keep communities and the environment safe really is to replace it," she said, with newer technology, with stronger and thicker steel.

A new Line 3 would also let the company ship more oil, another 370,000 barrels a day. That would help meet the demands of oil refineries, which Enbridge argues are not getting what they need when they need it.

In the past, those arguments would more than likely have been enough to convince the state to rubber-stamp the plan.

But after environmentalists targeted the proposed Keystone XL project for its impact on climate change, and thousands of Native American activists focused international attention on the Dakota Access pipeline last year, companies proposing oil pipelines find themselves under greater scrutiny.

Enbridge has entered into a consent decree with the United States Department of Justice as part of a settlement for a major spill in Michigan's Kalamazoo River in 2010, which calls on the company to replace the existing Line 3 provided it receives the go-ahead from the state.

So, to Enbridge, rather than continue to patch a degrading line, it makes more sense, both to the environment and to their bottom line, to build a new pipeline with new technology and new materials, even one that will cost $2.1 billion in Minnesota alone.

That's partly because the new line would also allow the company to transport more oil, more efficiently. That expanded capacity is crucial, Enbridge argues, because there's more demand for oil from Western Canada than there are pipelines to transport it.

The next 'Standing Rock'?

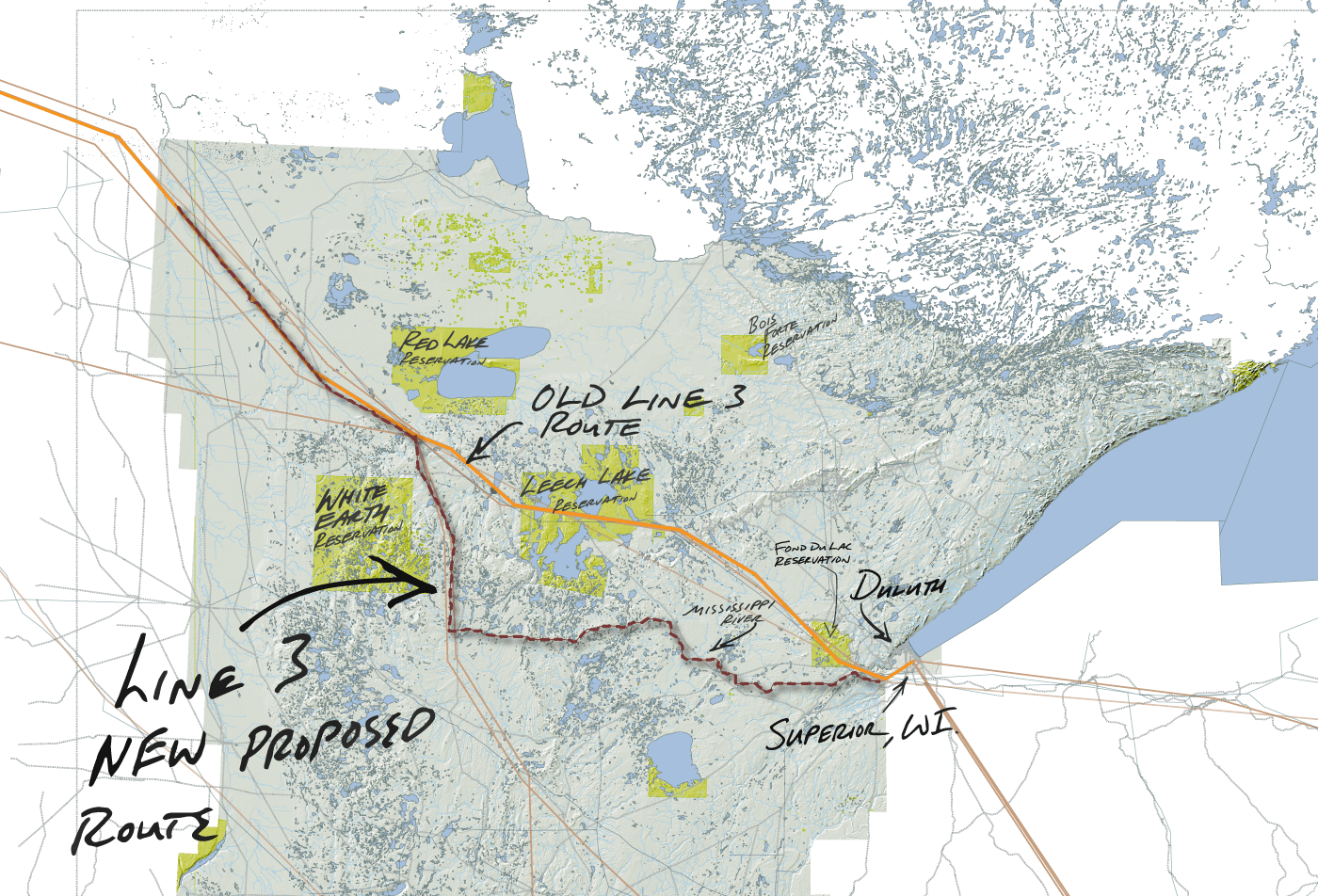

The new Line 3 if approved would cut a largely new corridor across northern Minnesota. While the new pipe would track the original line's path to Clearbrook, Minn., the pipeline would then jut south toward Park Rapids, Minn., before cutting east to the Wisconsin border south of Duluth, Minn.

The new route swings around the Leech Lake and Fond du Lac reservations. But it crosses through land where Native Americans have hunted, fished and gathered for centuries, land dotted with some of the cleanest lakes in the state, some of the richest yielding wild rice waters in the state, and the headwaters of the Mississippi River.

That has raised sharp objections from conservation groups and Indian tribes. They point to major spills in Minnesota in 1991 and 2002, and more recently to the 840,000-gallon Kalamazoo River spill that required a $1.1 billion cleanup. They say the risk of a similar spill in northern Minnesota is too great.

That growing opposition has led to tense protests with activists chaining themselves to pipeline construction equipment and to the doors of banks investing in Enbridge.

Protest camps have sprung up, and some are threatening that Minnesota will see "the next Standing Rock" if it approves Line 3, a reference to the massive demonstrations that broke out in North Dakota over the Dakota Access pipeline.

What's in it for Minnesota?

Think of Enbridge's mainline pipeline system through Minnesota as a multi-lane highway, with Line 3 in one lane, and other pipelines in other lanes.

At Enbridge's hub in Clearbrook, Minn., near Bemidji, there's a major off-ramp, where about 400,000 barrels a day is transferred to another pipeline system that serves Minnesota's two refineries in the Twin Cities; the rest of the oil continues to Superior, Wis., and on to refineries across the Midwest, and down to the Gulf Coast.

So while Line 3 itself doesn't deliver oil to Minnesota refineries, it's part of a larger network of oil pipelines that serves those refineries, as well as others in the region that produce products ultimately consumed in Minnesota.

The state's largest refinery, Pine Bend in Rosemount, relies exclusively on oil from Enbridge. It doesn't take crude delivered by rail or trucks. It expects to be a shipper on Line 3 if it's approved, said spokesman Jake Reint.

In the past decade more than 1 million barrels per day of pipeline capacity has been added downstream of that Clearbrook off-ramp, Reint said. But there hasn't been a corresponding growth in Enbridge's capacity to carry that oil to Clearbrook.

"If Line 3 were not replaced, you have less access to crude oil that we need to meet the transportation fuel needs of the region," Reint said. "And then you also have less reliability of a system on which Minnesota relies." Minnesota is also part of a broader oil market, Enbridge argues, in which refined products from Minnesota are exported to neighboring states, and products from other states are imported. But, in a surprise to both supporters and opponents of the project, the Minnesota Department of Commerce submitted testimony in September 2017 arguing refineries in Minnesota and the Midwest already have sufficient supplies of crude oil and little capacity for processing more of it.

The department also said Minnesota's demand for gasoline and other refined petroleum products was unlikely to increase over the long term. Not only does Minnesota not need a new, expanded Line 3, the department argued, the state doesn't even need the old one.

"In light of the serious risks of the existing Line 3 and the limited benefit that the existing Line 3 provides to Minnesota refineries, Minnesota would be better off if Enbridge proposed to cease operations of the existing Line 3, without any new pipeline being built," said the filing by Kate O'Connell, manager of the department's Energy Regulation and Planning Unit.

Gov. Mark Dayton acknowledged that his agency's report would "arouse considerable controversy. That discord should be recognized as part of the wisdom of the process," he said, adding that he would wait for the "complete record" before offering his personal views.

Enbridge called the state's analysis "flawed," and said it "fails to take into account the immediate negative economic and supply consequences to Minnesota were Line 3 to be shut down."

But many analysts say an expanded Line 3 would likely serve the Gulf Coast, where more than half the country's refining capacity is located, and where those refineries are configured to process the heavy crude that's produced in Canada's oil sands.

It would also fetch higher prices for Canadian oil producers, who have had to discount their crude because of pipeline constraints.

Increased oil shipments from Canada would likely displace oil currently being imported by Gulf Coast refineries from Venezuela and other Latin American countries, said Sandy Fielden, director of research for commodities and energy at the investment research firm Morningstar.

Oil demand in Minnesota, though, has remained flat for the past decade, and many analysts forecast demand will further decline in the future as electric vehicles become more widespread.

"If oil demand is not going to grow for Minnesotans and surrounding states," said Lorne Stockman, a senior research analyst at Oil Change International who filed testimony on behalf of Honor the Earth, "why should you host a risky, dirty oil pipeline?"

Enbridge counters that the refineries need a new Line 3. "Whether you like it or not," said Smith, Enbridge's community engagement manager, "we need to continue to have a reliable, secure stable source of oil, and an economical source, too."

Local flashpoint, national impact

The five members of the Minnesota Public Utilities Commission are expected to decide in June whether to grant Enbridge its certificate of need permit.

In making that decision, the PUC must weigh whether denying the project "would adversely affect the future adequacy, reliability or efficiency of energy supply" to Enbridge, its customers, or to the people of Minnesota or neighboring states.

The commissioners also must consider any more reasonable alternatives to the pipeline, and whether "the consequences to society of granting the certificate of need are more favorable than the consequences of denying the certificate." That means weighing the benefits to the state against the environmental and social risks.

"Neither the statutes nor regulations instruct them to weigh one more heavily than the other," said Kevin Lee, attorney with the Minnesota Center for Environmental Advocacy. "It does give them a fair amount of latitude to put more weight on one factor rather than another."

An administrative law judge has recommended the PUC approve Line 3, but only along its current route — not the new route Enbridge has proposed. Historically, regulators have given a lot of deference to industry. But the national debate around pipelines and other fossil fuel projects has shifted markedly since the last time Minnesota approved a pipeline, Enbridge's Alberta Clipper expansion in 2013.

Heightened publicity has allowed opposition groups to hire additional experts to analyze the Line 3 proposal, said University of Minnesota energy and environmental law professor Alexandra Klass.

Regulators are increasingly taking more skeptical stances toward pipelines and other fossil fuel projects, she added.

"The internet and social media means that projects like Keystone and Dakota Access aren't just local issues anymore," said Klass. "These are big, national issues."