Rights and protections at the heart of spat between prosecutor, police

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

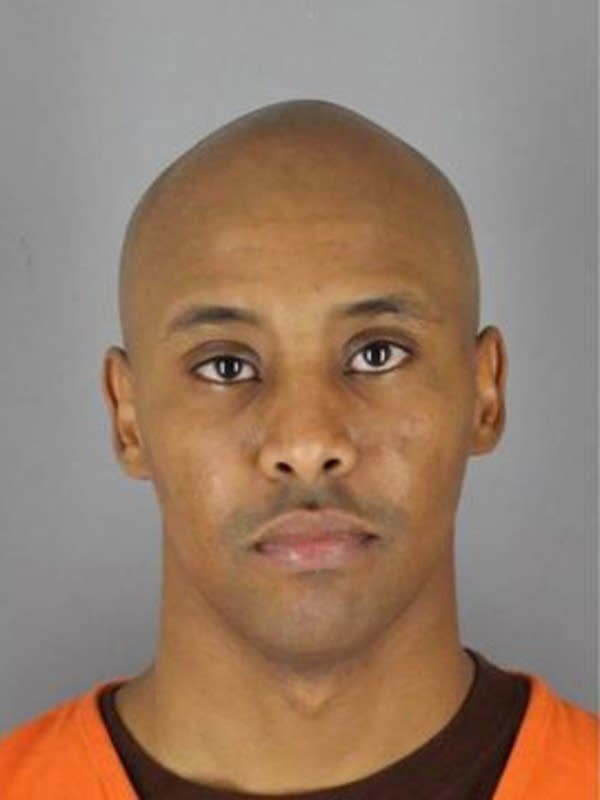

When he announced charges against former Minneapolis police officer Mohamed Noor Tuesday, Hennepin County Attorney Mike Freeman took a swipe at Minneapolis police officers, who he said refused to cooperate with his investigation into the shooting death of Justine Ruszczyk.

"A number of the officers, for reasons we do not understand ... refused to come answer questions," Freeman said at his Tuesday news conference. "I've been privileged to have this job nearly 18 years, I've never had police officers who weren't suspects refuse to do their duty and come forward to talk to us."

The moment highlighted the awkward — and sometimes fraught — relationship between prosecutors and police, when it comes to investigating police shootings. Prosecutors depend on law enforcement investigations to build their cases — and officers, in police shootings, end up investigating their own.

Freeman said several officers' refusals to be interviewed in his investigation forced him to convene a grand jury — which has subpoena powers to compel witnesses to testify — as an investigative tool in the case.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

But Minneapolis police officers and union officials said that this was not about a "blue wall of silence." Instead, they say, in going directly to officers instead of through the department, the prosecutor skirted a process that would have offered them immunity from prosecution, if their testimony became incriminating. And in refusing to be interviewed, they said, officers were exercising their right under a federal law that protects public employees from criminal prosecution.

Freeman's office spent six months looking into Ruszczyk's shooting death, which happened last summer in the alley behind her Minneapolis house. She'd called 911 to report what she thought sounded like an assault. Noor and his partner responded to the call, determined there was no threat, and, according to the criminal complaint, had been "startled" by Ruszczyk approaching their car from behind when Noor shot her.

State investigators handed the case over to Freeman's office in September of last year. On Tuesday, he charged Noor with third-degree murder and second-degree manslaughter, charges that allege he had a "depraved mind" and was "culpably negligent" when he fired the fatal shot.

"And I'm here to say this office will cooperate with Minneapolis cops, with the sheriff's office, with the BCA, we need to and we will," Freeman said at the news conference. "But we will not stop getting all the evidence even if we have to ruffle some feathers."

One officer who did cooperate with the investigation, Freeman said, was Minneapolis police chief Medaria Arradondo. In a news conference a few hours after Freeman's announcement, Arradondo echoed the prosecutor's assertion that officers should cooperate with criminal investigations, but with a caveat.

"There is a legal law called Garrity," he said. "[It] compels an employee [to] come in and answer. But it could also have a particular consequence. I had to be very mindful of that."

The Garrity law comes from a 1961 case in which a New Jersey police officer was threatened with dismissal if he didn't answer investigators' questions. He was ultimately forced to submit to an interview, and his statements from that investigation were used against him. The U.S. Supreme Court later ruled that the officer's Fifth Amendment right against self-incrimination and his superiors' insistence that he be interviewed had forced him into an impossible situation: To choose between his job or his right to remain silent.

Now, all public employees, when compelled to answer questions by their employers during any type of investigation, must be given the Garrity warning. Employers are required to inform the employee that their answers cannot be used against them in criminal proceedings.

"We expect every employee to cooperate with an investigation," Arradondo said during his news conference. "In this particular case, the county attorney's office chose not to go through my office to direct officers to give a statement."

It's not unusual for prosecutors to request additional information during an investigation. Police officers file their reports, and it's typical for prosecutors to ask them additional questions that go beyond the written report.

But in this case, the Hennepin County Attorney's Office confirmed that it had deliberately bypassed the official channels when asking for police officers' cooperation.

"Under the complex employment and criminal justice rule and the Garrity court decision, it would not have been beneficial for the prosecution, for the police chief to compel testimony," Freeman's office said in a statement.

The Minnesota Bureau of Criminal Apprehension, which investigates police shootings in the state, handed off their investigation of the case to the Hennepin County Attorney's Office six months ago.

The only witness, besides Noor himself, was his partner, officer Matthew Harrity, who told BCA investigators he had been "startled" by a loud thump near their SUV, as they were parked in the alley behind the house where Justine Ruszczyk had called police. That's when Noor fired his weapon, across Harrity and through the open driver's side window.

It's not clear whether Harrity gave additional interviews to the county attorney's office. But when Freeman decided to empanel a grand jury to use its subpoena powers, Harrity, along with about 40 other officers, were called in to testify.

It may not be readily apparent how the statements of a public employee who's not the target of an investigation might create problems for that person later on. That's where the Garrity rule comes into play.

"There may be situations where that individual may be facing some sanctions for having aided and abetted or been a co-conspirator on something," said University of Minnesota law professor JaneAnne Murray. "This is why the warnings would be applied to anybody in the context of an internal investigation or an external investigation."

But when Freeman convened the grand jury in the Noor case, the Garrity warning — and the protections that come with it — didn't apply. Grand juries have subpoena power to compel witnesses to testify. Their proceedings are secret, and they are typically used to investigate alleged crimes and recommend charges.

In 2016, Freeman had vowed to stop sending police shooting cases to grand juries in the wake of the 2015 killing of Jamar Clark by a Minneapolis police officer following a confrontation. At the time, he said charging decisions on police shooting cases would be handled by his office going forward, breaking with longstanding practice.

But in January, he convened the panel in the Noor case, about a month after he was caught on tape at a holiday party saying he didn't have enough evidence to file charges against Noor. He later apologized for the incident, and for blaming the BCA for "not doing their jobs." At the time, he also said Harrity did not provide what he said was enough information.

The statements have been hard for some police officers to swallow. And their impact lingers. After the charges were announced this week, the Somali-American Police Association released a statement calling them "baseless and politically motivated, if not racially motivated as well."

They didn't come as a surprise, the association added, saying that Freeman's intentions were clear long before he announced his decision.

"We believe Freeman is more interested in furthering his political agenda than he is in the facts surrounding this case," the statement said. "The charges brought against Officer Noor are not intended to serve justice; rather, they are meant to make an 'example' of him."

But Freeman stressed that he came to a charging decision after a complete and thorough investigation. He said officers who testified included those who'd responded to the scene, and others who answered questions about police training.

Still, police officials say this investigation has deviated from past practices. Bob Kroll, president of the Police Officers Federation of Minneapolis, said in a statement that many officers subpoenaed "had no involvement whatsoever with the incident."

"Mr. Freeman's underlying motive for requesting voluntary statements of our members was to strip them of their Garrity rights provided to public employees under law," the statement said.

Kroll hasn't returned requests for comment

The relationship between the prosecutor and police is likely to be tested in the coming months, as the Noor case works its way through the courts. Both Freeman and Arradondo said they'll continue to move forward and work together.

It's "good for all of us," Freeman said, when the "tension is positive and affirmative."