Landlord battles haunt Twin Cities low-income renters

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Lakesha Davis and her fiance Steven Perkins thought they'd finally landed a home, a house in St. Paul that offered a fresh start for them and four of their kids.

Years earlier, they'd been forced from their north Minneapolis home after a grandson's blood tests came back showing elevated lead levels. The landlord evicted them, Davis said, after the child's pediatrician alerted a city housing inspector.

They'd struggled to find traction after that in an extraordinarily tight rental market, which is why the St. Paul house was so important. The landlord had the deposit and said they could move in the very next day. "We just got to run your name and check it and if everything checks out, then you can move in," Davis recalled the woman saying.

Instead, they got a harsh lesson in how past problems with a landlord seem to never die. Their background check came back showing five "UDs," shorthand for unlawful detainers, the legal term for when a landlord tries to evict someone.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

While unlawful detainers are almost always about missed rent, they also capture other kinds of fights with landlords that have nothing to do with rent. The UDs the landlord wrote up for Davis and Perkins, for instance, included one for letting in the city inspector who'd been alerted to possible lead poisoning. It's not clear if that's legal.

In any case, most UDs aren't supposed to stay on the books. Minnesota courts' policy dating back to 1988 strongly recommends UDs be deleted from the public record after one year if they were settled with no financial transactions or if there was a court decision with no monetary judgment.

But that doesn't happen because the state court system doesn't have the technology to track UDs and follow its own guidelines, so the information lingers.

Davis and Perkins wouldn't have any evictions on their record if the court system followed its own record keeping guidelines.

'What good does it serve?'

Unlawful detainers show up on tenants' records any time a landlord files paperwork for an eviction. It doesn't mean the renter was evicted like Davis and Perkins. It just means the landlord started the eviction process.

Davis and Perkins settled four of their UDs out of court. In those cases, they had fallen about a month behind in rent. They paid the landlord to settle the case. In two instances they even stayed in their home and continue renting from the landlord who tried to evict them.

These all happened between 2011 and 2013, but they say it still makes it nearly impossible for them to find a house to rent.

Even if a judge rules in the tenants' favor or if the two sides settle out of court, the letters "UD" stay there.

Landlords say they don't write up UDs lightly and that they are a last resort when renters don't pay or don't comply with the terms of the lease and action must be taken.

In the Perkins and Davis case, a judge ultimately ruled against them because they didn't have renters insurance, which the landlord required (Perkins and Davis said they didn't know they were supposed to have renters insurance), and Perkins had a criminal history and wasn't technically allowed to live there since his name wasn't on the lease.

In many cases, eviction attempts really tarnish the reputations of tenants who actually would be good renters. A survey by a city of Minneapolis team found nearly all eviction cases, 93 percent, were over an average of two month's rent, or $2,000.

"Really, what good does it serve the public to know about an eviction where a tenant allegedly failed to pay rent, paid the rent the landlord said they owed and kept living there," asked Georgina Santos, a lawyer with Mid-Minnesota Legal Aid, where Perkins and Davis sought help. "That's a lot of the evictions that we try to get expunged."

In some cases, a tenant may have paid the rent they owed before ever going to court, or a tenant could be withholding rent purposefully, Santos said.

"A lot of these nonpayment evictions are triggered not because a tenant doesn't have money but because you have a tenant that is upset about living in a property where there are rampant health and safety violations," Santos said. "And so they withhold their rent money to try and force repairs not fully understanding the the long standing repercussions that this can have on their housing and their ability to find new housing."

'Love to give you the house, but...'

The inspectors who came to the house Perkins and Davis rented in north Minneapolis tested the walls and windows "and it was full of lead," Davis said.

Steve Meldahl, the landlord who evicted them, eventually had his rental licenses revoked for not maintaining his properties.

Their lease stated they weren't allowed to let in any inspectors without their landlord or one of his employees present. If they did, they would be charged $500 and evicted. Meldahl said he requires he be present for inspectors because he doesn't trust city inspectors to do a good job.

"I hate to say this but you know the fact is that contractors who can't make it in the contracting business become inspectors," Meldahl said. "They hire these people literally off the street... and they give them the housing inspections manual and tell them to go enforce it."

In the Perkins and Davis case, Meldahl said they hadn't lived in his property long enough for the grandson's lead levels to be high, so he thinks he got it from their previous home. He said he remembers being prompted to review their file after neighbors complained of loud noises, not because of the lead inspection.

Tenant screening reports don't show many details about the case. They may not even say why a landlord tried to evict someone. Landlords don't know why tenants were behind on rent or what provision in the lease they broke. They don't know if the tenants were selling drugs or didn't have renters insurance.

"[One landlord] said I'd love to give you guys the house but I can't give you guys the house because the simple fact is you have these UDs on your record and I don't know the meaning of your UDs," Perkins said.

Wipe the slate?

In a tight rental market, the letters "UD" cast a long shadow. The latest rental data released this month shows average rents are at an all-time high and vacancy rates are sitting at near-record lows. That means landlords can afford to be very picky about who they rent to. That's how Davis and Perkins ended up with the landlord they have now, Mahmood Khan. He was the only one who would rent to them. Khan recently had all his rental licenses revoked for not maintaining his properties.

Evictions are a common occurrence in North Minneapolis, a predominantly black neighborhood. One survey by the city's Innovation Team estimates nearly half of all residents in North Minneapolis had a landlord who tried to evict them in the past three years.

The two zip codes that have the most eviction actions are both on the north side.

Tenant advocates say a handful of landlords on the north side have evictions baked into their business, requiring tenants to pay two or three months' rent as a deposit, which the landlords keep along with court fees when they evict. It's a strategy that landlords say is rarely seen in the Twin Cities outside of north Minneapolis.

The Minneapolis survey found that Khan ranked fifth among landlords in the number of evictions he filed. Meldahl, the landlord who evicted Perkins and Davis, ranked fourth.

The year the study was done in 2015, they found Khan and Meldahl tried to evict nearly 80 percent of their tenants. The judicial branch doesn't have the technological capability to automatically delete records in accordance with their guideline. A spokesman said they hope to have a technological solution in place in the next couple years but didn't have more details on where they are in the process.

Evictions are concentrated in Minneapolis: Report

Page 7 of Evictions in Minneapolis Report

Contributed to DocumentCloud by Will Lager of Minnesota Public Radio • View document or read text

The guideline was created in 1988, before Minnesota had a digital database that anyone with a computer can access. Back then, paper files were housed in district courts for a minimum amount of time and then either destroyed or shipped to St. Paul for safe keeping.

When the state finished its digital rollout of the Minnesota Court Information System in 2008, most courts around the state started uploading their court files directly to the state's digital archive. And MNCIS didn't include a way to deal with files that would otherwise be deleted. Everything became very permanent and easily accessible.

There is a way for tenants like Davis and Perkins to wipe the slate clean if they can convince a judge to expunge their records, but that requires professional legal help. Davis and Perkins recently attended a free legal clinic in north Minneapolis host by Mid-Minnesota Legal Aid and the Volunteers Lawyers Network.

The expungement clinic was hosted specifically for Khan's dozens of tenants, many of whom have UDs on their records.

Perkins and Davis met with volunteer lawyer Kate DeVries Smith, who spent more than an hour going through each of their five UDs to start the months-long expungement process. To argue for expungement, DeVries Smith must convince the judge of two things:

"We have to show that the complaint should never have been filed in the first place and then we also have make a showing that harm to the tenants of having this on their record outweighs the harm to the public not knowing about the full record," DeVries Smith said.

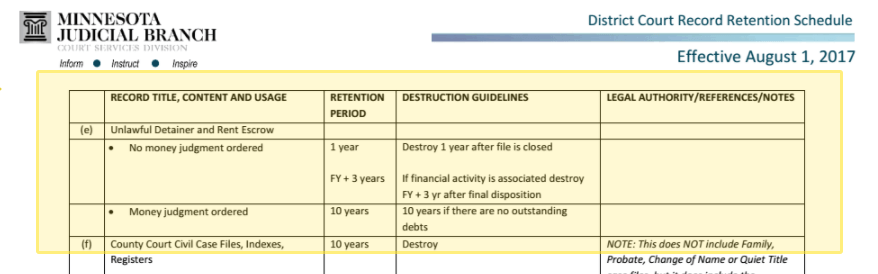

When to keep or destroy records

The Minnesota Judicial Branch provides the District Court Record Retention Schedule, a series of guidelines for when to keep or destroy court documents. According to the guidelines most eviction records, known as "unlawful detainer" should be destroyed a year after the case is closed.

'The true problem is money'

Mid-Minnesota Legal Aid and the Volunteers Lawyers Network say they file hundreds of expungement requests a year in Minneapolis alone. Like Davis and Perkins, most of their clients are dealing with eviction cases they settled for unpaid rent.

Carol Buche, who owns Twin Cities Tenant Check, a company that does background checks for landlords, says landlords don't enjoy filing eviction notices and that knowing that a landlord jumped through those legal hoops, no matter the outcome, is important information for other landlords.

"A landlord's opinion is if another landlord had to go to court to settle a problem then that in itself is enough," Buche said. "And the courts also put enormous pressure on parties to settle. And in the court's mind it seems to be that if the case was settled then the tenant won. No no no no. There was still a violation of the lease... a settlement doesn't tell me what the true outcome of the case is."

Buche's company buys data directly from the courts. Since the Minnesota Judicial Branch doesn't delete unlawful detainer records in accordance with its guidelines, they show up in Buche's tenant screening checks. Her company just removes eviction records older than seven years, in accordance with federal law.

Buche said she thinks the damage an eviction case does to tenants is overblown.

"The advocates are always harping that someone has one eviction and they can't find a place to live. This just doesn't happen 100 percent of the time," said Buche, adding that that tenants would have a better chance finding a place to live if they were upfront about their rental histories on rental applications.

"I can't tell you how many of my clients say if they had only been upfront with me I might have given them a chance," she said.

Even if the Minnesota Judicial Branch had the capability to comply with its guidelines, Buche thinks it wouldn't make anyone better off.

"It just kicks the can down the road. Hiding the record, so that person can get housing ... they're just going to turn around and get evicted again if we don't address the true problem," Buche said. "And of course, the true problem is money."

Perkins and Davis are on a fixed income. They both receive Social Security and making that stretch for themselves and their kids is sometimes an impossible challenge. Their income has not kept pace with rents in the Twin Cities which have reached record highs.

In their latest housing study, Marquette Advisors report the average cost of a three-bedroom unit in Minneapolis is $1,885. Perkins and Davis want to find something closer to $1,400.

Evictions can also cost tenants a lot of money. Perkins and Davis have lost deposits. They've had to abandon new furniture they couldn't afford to move. And they say their options for who they rent to are limited by their record, so they have to pay more rent for worse conditions. Still, they're hopeful expunging their record will let them find a place to stay long-term.

"I mean, Minnesota be a great place as long as these landlords get it together," Davis said.

Editor's Note (Feb. 22, 2018): An earlier version of this story said the district court's record retention schedule "calls for" UDs settled with no financial transaction or court-ordered monetary judgment to be deleted after one year. To clarify, the court's schedule "strongly recommends" their deletion.