Troubled Waters: Trump budget casts Great Lakes cleanup into doubt

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

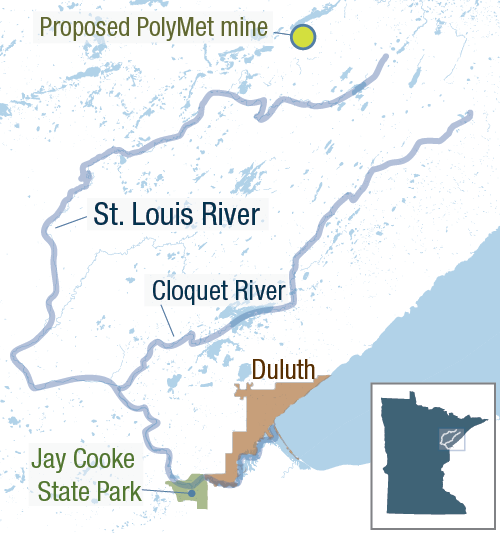

Cruising upstream in Rob Maas' fishing boat, it's nearly impossible to see the St. Louis River's long history of industrial pollution.

Fewer than 10 miles from downtown Duluth, thick forests line the estuary's shores. An eagle nests in a tall pine. Ducks and other waterfowl maintain their incessant chorus.

But underneath the water's surface lingers a toxic legacy left behind by more than a century's worth of heavy industry, logging mills and a giant steel mill where Maas used to work.

One hundred years ago, U.S. Steel built a massive mill along the banks of the river southwest of Duluth. It even built an entire neighborhood to house the workers, dubbed Morgan Park, after J.P. Morgan.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

A half century ago, Maas worked at the Duluth Works, making barbed wire that was shipped to Vietnam. He raised his kids just blocks from the river.

"I used to come down here and fish with them," he recalled. "But if you took them home and cooked them, your house stunk, they just smelled terrible. You could tell they weren't healthy or clean."

He points to an area his kids used to call "the hots," because the water was always so warm. They used to spear carp there, he said. It was where U.S. Steel discharged coal tar, a byproduct of the steel making process.

Since that time, the river has made a remarkable comeback. The steel mill closed in the 1970s. Water quality improved tremendously in the 1980s after a sewage treatment plant went online.

Maas, who's 71 now and retired, sporting a walleye fishing cap, black sunglasses and white sunscreen smeared across his cheeks, fishes the river more than 200 days a year. He's even able to eat much of what he catches. Giant lake sturgeon are now successfully reproducing on their own in the river, decades after they were wiped out.

But despite the environmental progress, toxic contaminants still remain trapped in the river's sediment. The coal tar discharged by the plant formed a delta that's 17 feet thick in some places, said Mike Bares, a hydrogeologist with the Minnesota Pollution Control Agency.

Altogether there's enough contaminated muck to fill more than 800 Olympic-sized swimming pools. It's the largest contaminated sediment site in Minnesota, and one of the largest in the country.

"It's really hard to see contamination that's under the water," said Bares. "But this is what it's all about. It's in the aquatic ecosystem, and it really is causing some major issues."

The pollution, Bares explained, harms microscopic critters living in the muck that form the base of the food chain. Clean that up, and all the bigger fish and wildlife can thrive.

That prospect has Rob Maas excited.

"Because I use it, I use it every day," he said. "I have people who come and fish with me from California, Las Vegas, Florida — all over the country, and they can't believe, when you're out here, you don't even know you're by a city."

It's taken several years, but state regulators, the Environmental Protection Agency and U.S. Steel have finalized a plan to clean up the sediment, to dredge and remove much of it, and to cap other areas so the pollution can't escape.

It calls for the EPA to cover a little over half of the $69 million price tag, with U.S. Steel picking up the rest.

But now the cleanup work is in jeopardy. President Trump's proposed budget to Congress calls for cutting $300 million for the Great Lakes Restoration Initiative.

The St. Louis River estuary is the second largest of more than 43 areas around the Great Lakes prioritized for cleanup under the federal effort since 2010.

Dredging and capping the U.S. Steel pollution is just one part of a broader effort to clean up the entire St. Louis River estuary. After three decades of work, a plan is now in place to finish cleanup work by 2020.

That includes $72 million to clean up 10 other contaminated sediment sites in the river, aside from the U.S. Steel project. State lawmakers recently approved $25.4 million to fund that work over the next three years.

But Nelson French, who supervises the cleanup work for the MPCA, said state and private funding leverages needed federal investment.

"We're just at a juncture where the feasibility studies have been done, the designs are about to start, and we now have this uncertainty thrown at us," said French.

If federal funding comes through, an EPA spokesperson said work on the U.S. Steel project is scheduled to begin next fall. A spokesperson for U.S. Steel says the company can't speculate about future federal funding.

But the city of Duluth is banking on it. It has ambitious plans to revitalize the riverfront to spark neighborhood and economic development and create new recreation opportunities.

Duluth's director of public administration Jim Filby Williams said its vision to jumpstart development on the western side of town depends on the completed restoration of the river.

Correction (June 12, 2017): A previous version of this story included a photo caption that misidentified Mike Bares. This post has been updated to correct the error.