For adopted kids, having American parents doesn't always mean U.S. citizenship

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

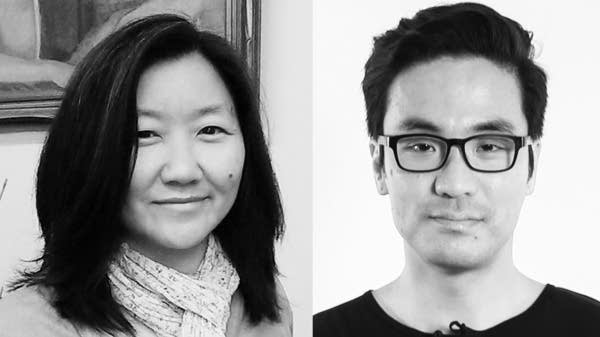

Amie Kim knew she wasn't like other kids in her Fridley neighborhood. But she tried to fit in as a Korean adoptee being raised by a Lutheran family. She attended churches in Columbia Heights and Eagle Lake. She was an honor roll student, a cheerleading captain in high school. And when she turned 18, she went to her school gymnasium to vote. But it turns out that she's not a U.S. citizen.

"My adoptive parents are flag-toting, Republican, patriotic types," said Kim, who is still only a green-card holder. "[When] I was in my early 20s, and I was hanging around my other Korean adoptee friends, and they were all telling stories about what it was like for them when the were naturalized. The flag was there, and they raised their hand, and said the words they were supposed to, and I found it funny that my adoptive parents never took pictures of that."

Her adoptive parents didn't do the necessary paperwork required to grant citizenship to Kim, so she and other adult adoptees are now raising awareness about an unknown number of foreign-born children who continue to face hardships because of their status.

"I actually feel that my current status, as not exactly a Korean citizen and not exactly a U.S. citizen, it actually fits my identity and how I feel about myself," said Kim.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

A bill introduced by Minnesota U.S. Senator Amy Klobuchar could retroactively give Kim and other adoptees like her U.S. citizenship.

"We're dealing here with adoptees, who grew up in American families, who went to American schools, who led American lives, and are still leading them," said Klobuchar. "Yet adopted kids who are not covered by the Child Citizenship Act just by a fluke of history are not guaranteed citizenship."

It's unclear how many adoptees would be affected by the bill. The Child Citizenship Act of 2000 automatically granted citizenship to most foreign-born children, but not to those who were already 18 and adopted years earlier. Klobuchar, who is co-chair of the Congressional Coalition on Adoption, says those adult adoptees have faced many hurdles, including rejection from colleges or getting turned down from jobs.

"And the constant threat to the life that they know is really unjust," said Klobuchar. "And that's why I'm working to move my bi-partisan bill forward, and it will ensure that international adoptees who came legally into this country are recognized as the Americans who they truly are."

Supporters of the bill include Kevin Vollmers with the group Gazillion Strong, a multimedia storytelling organization in Minneapolis.

"This is a human rights issue," said Vollmers, who is a Korean adoptee with U.S. citizenship. "There are folks who are tying this in with anti-immigration sentiment ... Regardless of what people think about anti-immigration or immigration, this question is fundamentally about adoptions.

"Adoption is a legal business, in which a legal case is made that kids from vulnerable countries are brought into the United States, and the federal government promises to the other governments [and parents] that they will get all the rights and privileges as though they were born into these families."

Vollmers' group, and three other organizations, including the National Korean American Service and Education Consortium, plan to hold a Day of Action to raise awareness about the Adoptee Citizenship Act later this month.