Without support, Minnesota students left behind at graduation

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

When Xavier Simmons walked into class in high school, he'd turn his desk backwards, put his head down and go to sleep.

He failed four classes his freshman year. Nobody called him on it, he said — not his mother, not his teachers, not his counselors. He dropped out the next year.

"I didn't think of it as a big deal," Simmons said. "I didn't do what I was supposed to do. I took the wrong path."

One might say Simmons, now 27 and lacking a high school diploma, got what he deserved. He didn't try. But beneath his aloofness was a sense of desperation: He wanted to quit school so he could find work and help his mother pay the bills.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

In the end, Simmons, who is African-American, was free to flounder in a state where students of color have some of the lowest graduation rates in the nation.

Full coverage: How did we get here? What's at stake? And what will it take to find a solution?

Students like Simmons get knocked off track for a complex mix of reasons. But by one measure, Minnesota schools provide the weakest safety net in the country: No other state spends less of its education dollar on non-classroom student support.

Abysmal graduation rates for minority students have not only rattled education officials, but are worrying policymakers and civic leaders over the implications for Minnesota's economy. The state needs skilled workers. And the fastest-growing segment of the future workforce is students of color — the students least likely to earn diplomas.

Many schools here and elsewhere have improved their graduation rates in part by following a simple formula of early intervention. They identify students who are at risk of dropping out, then match them with the support they need.

But the effort requires staff power, and Minnesota as a whole lags in that support, especially for at-risk students. Schools here spend 2.6 percent of their education dollars on pupil support, a smaller portion than every other state. And it has been that way for a decade, according to an MPR News analysis.

These services run the gamut from attendance-tracking to counseling and can help serve the social and emotional needs of students to better prepare them to learn in the classroom. Interventions like that can be critical in pinpointing students who are off track to graduate.

A notorious 'party trick'

Just how bad are Minnesota's graduation rates?

Overall, 82 percent of students finish high school within four years, according to 2015 figures released last month. That's on par with the national average. About 87 percent of white students in Minnesota graduate on time, a rate that places the state near the middle of the national scale.

But if you're Hispanic, black, Asian-American or Native American, your chances of completing high school are worse in Minnesota than in almost any other state.

Only 62 percent of black students in Minnesota finish high school on time. According to 2014 figures, the most recent for which there are national comparisons, the graduation rate for black students in Minnesota is third worst in the United States. Black students in Mississippi and Alabama had significantly higher rates of graduating on time.

In 2014, Hispanic students in Minnesota had the nation's lowest on-time graduation rate. A year later, only 66 percent finished high school in four years. The rate for Native American students in 2015 was 52 percent.

The graduation figures stand out from many other measurements that illustrate Minnesota's racial divide in the classroom.

For example, the state sees a racial gap on standardized tests for math in the fourth and eighth grades because white students in Minnesota do exceptionally well on the test and the state's students of color fall in the middle of national rankings.

But when it comes to graduation rates, the more troubling disparity is between students of color in Minnesota and those in virtually every other state.

The figures are hard to swallow in a progressive place that puts a premium on education. Minnesota likes to boast that its school children score near the top on a variety of national tests and college-entrance exams.

And yet, the overall graduation rate for one of Minnesota's largest school districts, Minneapolis, has hovered around 50 percent in recent years, climbing to 64 percent last year.

Those numbers are surprising to people outside the state, according to one of the nation's leading experts on dropout trends.

"My party trick is always to ask people which city has one of the lowest grad rates. I always know they'll never win, because it's Minneapolis," said Robert Balfanz, a research professor at Johns Hopkins University. "It just doesn't come to people's mind as the most impacted, the most struggling urban city in America."

Around the country, Balfanz said, most other major cities have worked hard to lift up their graduation rates to percentages in the upper 60s or higher over the past decade or so.

In Minneapolis and in Minnesota as a whole, the rates have improved — but not as much as they have elsewhere.

"We have so much more yet to catch up with other states," said state education commissioner Brenda Cassellius. "Everything went up last year, but we have to be faster."

It's not just poverty

So, what gives?

Some education officials bristle at national graduation comparisons because the pathways to a diploma vary from state to state. In some states, different diplomas have varying credit requirements, so high-achieving students can demonstrate more academic rigor. Several states offer vocational-prep diplomas alongside college-prep options. Some alternatives are designed for students with learning disabilities and may not be accepted for post-secondary study.

Minnesota has relatively rigorous course requirements and only one kind of diploma, intended to prime students for college or careers.

On the other hand, there's no question that graduation rates measure a tangible outcome. Unlike test scores, a diploma has real-world consequences.

Two common theories emerge when educators and policymakers try to explain Minnesota's graduation gap: language and poverty.

In other words, to be black or Asian-American in Minnesota generally means to be poorer than in other places. The state also is home to thousands of immigrant students who are learning English.

Minnesota does have higher levels of poverty and more students with limited English skills among its communities of color, but they're not the highest rates in the country.

And when you look only at students of color who aren't poor and who are proficient in English, there are still gaps when compared to the graduation rates of white students. The on-time graduation rates for Native Americans, African-Americans and Hispanic students who are not poor, not English language learners and not in special education are lower than those of their white peers by a dozen percentage points or more.

"The system is old," said Michael Rodriguez, a professor of educational measurement at the University of Minnesota. "It was structured based on a time when we really didn't expect everybody to finish high school. The system is built and structured on, unfortunately, some exclusivity."

Traditional schools have worked best for white, middle-class children whose parents are also educated, said Rodriguez, a native of St. Paul's east side who was the first in his family to go to college.

Kent Pekel, CEO and president of the Minneapolis-based research firm Search Institute, agrees that the system hasn't adapted. Even though Minnesota is seen as a progressive state, Pekel said, there's a deep ethos that expects teens to pull themselves up by their bootstraps. Programs to help academically challenged students may have been available for many years, but often it was up to the students to seek them out.

Many schools lacked a systematic way of identifying kids in trouble, Pekel said.

"We've been a state where, for a long time, the number of struggling students was small. Now that group is growing the fastest," Pekel said. "I really think Minnesota has been asleep at the wheel for struggling teenagers."

Some schools have made progress in improving their graduation rates among students of color.

Patrick Henry High School in north Minneapolis, for example, where 92 percent of the students are nonwhite, has raised its overall graduation rate to 87 percent, surpassing the state average — and every other high school in the district.

But Pekel says there hasn't been a statewide strategy similar to Henry's.

"In Minnesota, we're kind of the land of 10,000 pilots," he said. "We have lot of interesting things going on over here or there, but we have this challenge of taking anything to scale and sustaining it over time."

The ABCs of dropout prevention

Researchers say the best predictors that a student will drop out have nothing to do with race, gender, income or even test scores. The chief warning signs are known commonly as the ABCs: attendance, behavior and course performance, Balfanz, the Johns Hopkins researcher, said.

That's one reason the efforts of guidance counselors, social workers, attendance trackers and other non-classroom support staff can be vital.

Minnesota schools spend a quarter-billion dollars a year on non-classroom pupil support — $301 per pupil in 2013. But that is only 2.6 percent of total education dollars, according to the most recent figures available from the U.S. Census Bureau. That's less than half of the national average of 5.5 percent. Since 2004, no state has devoted a smaller share to student support.

Minnesota wasn't always dead last by this measure. Support spending as a percentage of all education spending peaked in 2002, the year Tim Pawlenty, who promised no new taxes, was elected governor. Pawlenty, a Republican, helped slow the growth in state education funding while trying to balance the budget.

And he made clear his distaste for excessive spending outside the classroom. In 2006, Pawlenty proposed a plan that would require all districts to spend at least 70 percent of their budgets on classroom instruction.

The plan never made it through the Legislature, but schools got the message, said Karen Seashore, a University of Minnesota professor who specializes in educational improvement.

"It definitely put school districts on notice that they were not supposed to spend money on libraries or counselors," Seashore said. "They were supposed to spend money on teachers. Anything that was not directly related to classroom instruction was administrative bloat."

While Pawlenty appeared to view non-classroom services as peripheral, Seashore said support staff are keenly focused on nurturing students' academic success.

"The training that school counselors, social workers and school psychologists get is designed exactly to support teachers in doing this kind of diagnostic work so that they can be more adaptive to individual students," she said.

Schools were facing other financial pressures in the 2000s. There were recessions. Local school levy measures failed. And costs were going up for things like teacher salaries. Those circumstances forced individual schools and districts to make tough decisions.

"Every single thing that wasn't the core classroom was getting cut," said education commissioner Cassellius, then an assistant principal in Minneapolis Public Schools. "If we don't think that impacted our graduation rates, then we're fooling ourselves."

Student support as a share of total education spending has remained largely flat during Gov. Mark Dayton's administration.

Schools would need to spend $75 million a year more to get back to 2002 levels of student support, either by shifting existing cash or finding new revenue. To match the national average rate of 5.5 percent, they would have to add about $260 million, doubling what they spend now.

Advocates of school counseling and other support services are pressing Dayton, a DFLer, and the Legislature to get more serious about helping at-risk students. They're eyeing a piece of a state budget windfall projected at $900 million.

"If we don't start to address this now, when we have a budget surplus, my concern is we're never going to address it," said Walter Roberts, a professor of school counseling at Minnesota State University Mankato. "The excuse is always, 'We don't have the money.' Well, now we do."

A shortage of school counselors

In the 1970s and 1980s, many other states began to require schools to hire counselors, Roberts said. Minnesota has no such requirement and today it has one of the most severe counselor crunches in the country, particularly in elementary schools. Overall, Minnesota has just one counselor for every 743 students. That ratio places the state third from the bottom nationally.

Among high schools, Minnesota ranks closer to average, employing one counselor for every 394 students, compared with 360 nationally. State education officials say it would cost about $7 million to hire the number of high school counselors needed to bring Minnesota's ratio up to the national average.

School counselor-to-student ratios nationwide, 2014

MPR News graphic | Source: National Center for Education Statistics via American School Counselor Association

There's no guarantee that hiring more guidance counselors would fix the state's graduation woes. Counselors say they're straddled with administrative work, college referrals and other duties not directly tied to helping at-risk students complete high school.

But they might be instrumental in one area in particular. Researchers have found that many students realize too late they lack the credits to graduate. The system isn't organized to flag them, at least not early enough.

Shaneikque Barker, who is African-American, had a hard time at St. Paul's Central High School, where she found it difficult to follow her teachers. Although some tried to help her, she said they couldn't give her the attention she needed. When she finally saw a counselor, it was in the 11th grade, Barker recalled.

"And that's how I found out how far behind I was," said Barker, who is now 22. "I knew I was far behind, but I didn't think I was that far behind."

Dayton has appeared sympathetic to the counselor shortage in Minnesota schools, even citing the problem in his State of the State address a couple of years ago. Last month at a middle school in North Mankato, he listened to counselors, nurses and social workers as they made a case for funding that would allow schools like theirs to hire additional support staff. Dayton said he was moved by the stories they told him about students facing homelessness and mental illness.

He also said he'll consider finding money that could help pay for student support staff.

But he didn't commit to anything and stuck to a point: He said he wants to increase funding to school districts, and give them latitude to spend it how they see fit.

What more support looks like

Some schools have made that spending choice and seem to have seen results.

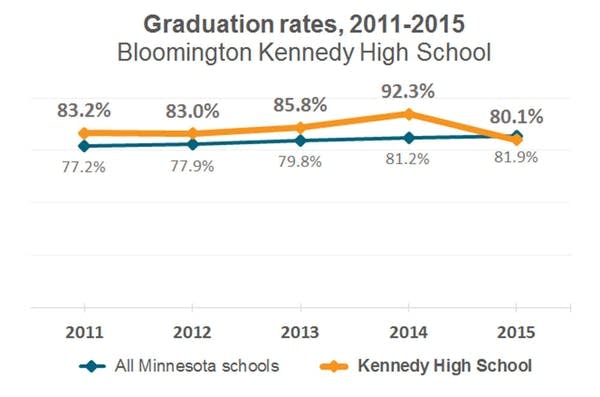

At Bloomington's Kennedy High School, the school's graduation rate, which peaked in 2014, has been fueled largely by gains among black and Hispanic students.

Mariana Camacho Castillo, a high school senior and the daughter of Mexican immigrants, transferred to Kennedy during her freshman year from a nearby school after learning she had failed most of her classes. Nobody at her old school seemed to notice that she had been skipping class, she said.

"They didn't really care," said Camacho Castillo. When it dawned on her that she was at risk of not graduating, she said it felt as though she was lost "in a dark circle."

At Kennedy, Camacho Castillo found a much stricter environment.

School staff routinely sweep the halls for students who are late. Kids who aren't on time are locked out of the classroom and need to call their parents before they are allowed back in.

Teens quickly discovered how annoying it was to call Mom during the school day. Tardiness incidents dropped by 20,000 the first year, said principal Andy Beaton.

Beaton said when he took the job in 2010, he wanted to heighten the expectations of Kennedy's students. Right away, visitors to the school noticed the difference.

"When visitors come, they're like, 'Wow, your halls are so quiet.' Well, kids are in class," he said.

Beaton imposed other changes aimed at helping vulnerable kids graduate on time. Intervention teams of support staff meet weekly to discuss individual students falling through the cracks. He also built academic support programs into the schedule of the school day, so kids can make up tests or get help with assignments without having to stay after school.

Critics, including some teachers, have pushed back against the idea of giving students too many chances to succeed.

"Some people feel like they need to learn from failure," Beaton said. "That can work to some extent, but not necessarily when it's going to impact a kid's life five to 10 years down the road. It's a life choice, and they might not have the capacity to make a good choice at the time."

Hiring to produce results

Beaton, who like the majority of his staff, is white, also set out to hire a more diverse staff to focus on the school's diversity of students. He created new positions, known as student advocates, to help all students, but especially kids of color, navigate high school.

One of those advocates, Raheem Simmons, runs an advisory class of mostly black males. Simmons, who is African-American, was raised by a single mother of eight children. He said he had attended 15 schools by the time he graduated.

Simmons picks a small group of students that includes the troubled — and the boys simply getting in trouble. Or they may just be kids who he thinks can become leaders of the school, with the proper guidance and support. Over several years, he said, not one of his students has failed to graduate on time. Simmons said he's also seen an uptick in their grades and attendance, and a decrease in their number of disciplinary referrals.

But he also demands a lot from them.

Earlier this school year, Simmons started his advisory class with a sobering ritual. He handed out papers listing each student's current grades. At the time, there were 20 Fs among the 16 boys.

"Don't give me crap about how you want to go to college, you want to be a professional, you want to do all this stuff, and you can't even do this stuff, man," Simmons told his boys.

After class, Simmons acknowledged he can be tough on his students. But when they're doing the right thing, he said, he's their biggest cheerleader.

"They know it's fair," Simmons said. "Whatever we have to do to get them to the point where they can graduate, that's what I want. But I will not settle for excuses. I just can't do it."

Another student advocate, Rosa Flores, meets just about every day with Mariana Camacho Castillo, the former transfer student. They talk about everything — grades, yes, but also work, life and family responsibilities.

Like many children of immigrant families, Camacho Castillo helps her family with babysitting. And because she also works, it's not uncommon for her to crack open her schoolbooks after midnight.

On top of that, Camacho Castillo lumbered through some rough patches in high school. Last year was especially treacherous: Her parents split up, and she was dealing marijuana. An older sister helped straighten her out.

Now, Camacho Castillo is on track to graduate in June. And she credits Flores, her advocate, for putting her on the right path.

"When I graduate, my thank-you will all be to her," she said. "Knowing you have one person caring for you in and out of school, it helps you a lot."

But graduation trends among individual schools can be tenuous. After several years of steady progress, Kennedy's four-year rate fell from about 92 percent to 80 percent in 2015, with an especially precipitous drop among Latino students.

Beaton, the principal, attributes the dip to a pilot program that gave more than 30 seniors who were eligible to graduate last year the option of remaining at Kennedy for a fifth year while attending nearby Normandale Community College. Those would-be graduates deferred their diplomas so they could receive counseling and other support from the high school as they transitioned to college.

Those students didn't graduate on time, but at least they'll get a diploma and have a better shot at finishing college, Beaton said.

Focus on freshmen

Support for students can be critical, especially in the ninth grade. Researchers say it's a make-or-break year. Students are figuring out their social circles. They have bigger responsibilities, and often less adult supervision in the schools.

Freshman year is exactly where educators at Patrick Henry High School in north Minneapolis are focusing their efforts.

In 2014, Minneapolis Public Schools started the PREP pilot program, based on research by the University of Chicago that found schools can improve graduation rates by monitoring ninth graders and intervening at the first sign of problems. Henry is one of three city high schools in the PREP program.

At Henry, 67 students have signed up for the PREP class. Middle-school counselors invite students whose attendance, grades, discipline records and reading scores indicate they might need help making the transition to high school.

At least twice a month, the students meet with several "graduation coaches" who volunteer with the group AchieveMpls.

Ninth-grader Mikerri Logan, who is African-American, said she didn't really pay attention to her teachers in middle school. She says it's helpful to be able to talk through assignments with her classmates in the PREP program.

"They're probably going through the same thing I'm going through, and we can probably help each other out," she said.

Logan's teacher, Rosa Costain, says PREP students get extra help with their school work. But the program also aims to teach social skills that will help students navigate high school — and life.

"If you don't yet know how to advocate for yourself or build relationships or speak up or ask for help or push yourself, and no one has ever taught you that, then how can we expect you to know how to do that?" Costain said.

It's too early to tell if PREP is working to improve graduation rates. But Costain said teachers have told her they've noticed students who have participated in PREP seem to be more attentive and engaged in class.

The school's total on-time graduation rate has steadily increased over the past several years. It climbed from 70 percent in 2010 to 87 percent in the 2014-15 school year. The four-year graduation rate for black students increased from 65 to nearly 80 percent, still lower than the rates of their white, Latino and Asian-American peers.

First-year principal Yusuf Abdullah, 39, who is African-American, said he recognizes that black students face unique challenges.

Henry is located in a part of the city which contains some of the poorest and most violent neighborhoods in the state. The residents of those neighborhoods are mostly black. Last October, a student brought a gun to the school.

Abdullah says too many black students see this dysfunctional world as normal.

"That reinforces the negative belief of who they are," he said. "It reinforces that they aren't going to amount to anything. So as teachers, as educators, as leaders we just have to combat that."

Last November, members of the group 100 Black Men Strong came to the school to have breakfast with around 200 black male students. The event was a hit with the students and the mentors, Abdullah said. He'd like to see the men in the school every day. But he knows it's not realistic to expect so many volunteers to spend that much time in the school's halls and classrooms.

There's only so much teachers, educators or even early intervention programs can do, he said. Black students need positive black role models to show students graduation is not only possible, but that it is a crucial milestone.

That lesson could have helped Xavier Simmons, the boy who used to snooze in class with his desk turned askew. Today, at 27, Simmons is no longer a boy. And although he's found lucrative work over the past decade, he landed those jobs only after lying about passing his high-school equivalency exams.

As a teen, Simmons spent a year at Henry High School before transferring to North High School, just a few miles away. By the time he dropped out as a sophomore, he only had seven credits to his name.

Back then, Simmons perceived school as time that could be better spent working.

"I wasted hours from 8 to 3," he recalled of his mindset at the time. "We have bills due, we need food."

Only years later did Simmons realize that an education "is everything."