Minnesota's graduation gap: By the numbers

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Full coverage: How did we get here? What's at stake? And what will it take to find a solution?

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

Minnesota's failure to graduate its high school students of color is among the worst in the nation. Students who are Native American, black, Hispanic or Asian-American are less likely to graduate on time than their counterparts in nearly every other state in the country.

Many achievement gaps that exist in the state — on middle-grade math tests, for instance — can be explained by white students performing near the top of the national scales and students of color toward the middle. But that's not the case with graduation rates.

The percentage of Minnesota's Hispanic students who completed high school in four years was the absolute lowest in the United States in 2014, the most recent school year for which there are national statistics. The rates for Native American, Asian-American and black students also hover near the bottom.

Education officials in Minnesota often balk at any state-by-state comparisons. They explain the racial graduation gap in Minnesota in part by pointing to the state's rigorous course standards and credit requirements, aimed at college readiness, that make the diploma more valuable than in other states.

But in this relatively challenging academic environment, where is the support for students who need the most help?

It's in another of those state-by-state comparison where Minnesota also falls to the bottom of the list: Spending on student support services. Minnesota spends a smaller share of its education dollars on student support like school counselors, social workers and attendance trackers than any other state in the nation — and it's been that way for at least a decade.

Education experts agree that schools should be challenging, but emphasize that they should also provide high levels of support for students in danger of falling through the cracks. Schools need staff and systems aimed at identifying students who are off track to graduate, they say.

The biggest predictors that a student won't finish on time? They're as basic as A-B-C: Attendance, behavior and course failure.

For many Minnesota schools, the resources to track those three predictors — and follow up on them — just aren't available. Guidance counselors, for instance, are in short supply across the state:Minnesota schools employ just one counselor for every 743 students. Unlike other states, Minnesota has no set requirement for a counselor-to-student ratio, and the state ranks third from the bottom nationally.

Is it any surprise, then, that students of color have trouble thriving in Minnesota?

Take Jasmine Lazo, an 18-year-old who dropped out of high school during her junior year. Her first signs of trouble came in the ninth grade, regarded by education experts as the make-or-break year for students. Lazo started ditching school. She failed freshman English and fell behind. She didn't ask for help from guidance counselors. Family problems compounded her academic performance, and then she quit school altogether.

Patrick Henry High School in north Minneapolis has seized upon the importance of freshman year. Incoming students who are identified as being at risk of dropping out, based on their middle school performance, are given more focused attention. The high school has dramatically turned around its graduation rates over the past several years.

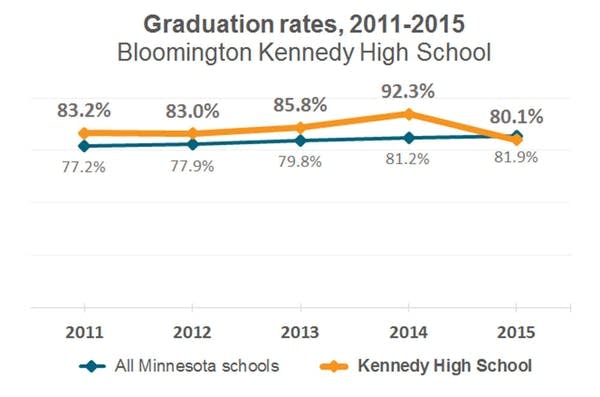

At Kennedy High School in Bloomington, where most of the students are low-income and racial minorities, administrators are trying to redesign the system to make it much more difficult for kids to fail. The school's philosophy is a simple concept: Identify struggling students early on, and match them with the support they need.

This approach has involved hiring more support staff, getting kids to class on time, meeting weekly to discuss struggling students and possible interventions and giving students more chances to make up homework and retake tests. The effort appears to be working. The school's overall graduation rate has climbed over the past decade.

These schools provide just two examples of success — but they're only two.

Minnesota is becoming more diverse by the year, so the state now has a growing economic problem because of the graduation shortcomings for students of color.

"We're running out of workers," said former Minneapolis mayor (and now education advocate) R.T. Rybak. "And unless we solve this thing, our economy is going to grind to a halt."

MPR News staffers Laura Yuen, Brandt Williams, Tim Pugmire, Bill Wareham, Laura McCallum, Will Lager and Meg Martin contributed to this report.