Is the criminal justice system as good as you think it is?

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

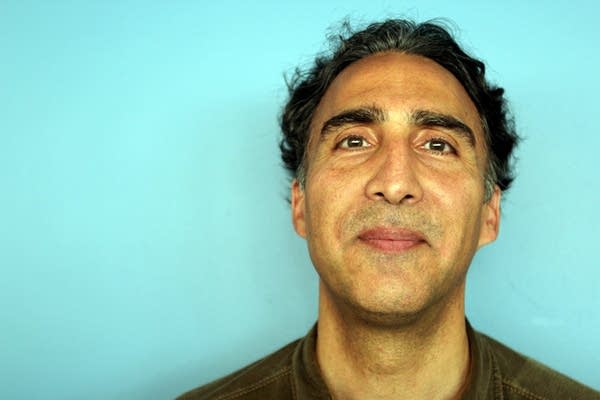

By John Radsan

John Radsan directs the National Security Forum at the William Mitchell College of Law. He is a former assistant general counsel at the CIA.

At age 15, Michael Saunders was charged with rape and murder based on a false confession. After serving 14 years in Illinois prisons, he was released just this year. DNA tests showed somebody else had committed the crime.

Even though his case is wrenching, I bet this is the first time you've heard his name. Sure, you've heard a lot about Khalid Sheikh Mohammed and other terrorists being arraigned in Guantanamo. We continue to fret about them, but for some reason we don't care about daily errors in criminal justice.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

Do we distrust Guantanamo because of the secrecy that surrounded detentions there? Is the remorse a counter to 9/11 hysteria? Or is it simply related to orange jumpsuits and the power of images?

Consider the Innocence Project at Cardozo Law School. That project has freed more people than are currently held in Guantanamo. Some of those freed were on death row. And the disparity in numbers between the two systems only gets bigger.

Criminal justice is supposed to be the gold standard for due process, the shining alternative to military commissions, extraordinary renditions, drone strikes and other things on the dark side. But is it as good as you assume?

I'm not so sure. But I do get less attention for my experiences as a federal prosecutor than for what I did at the Central Intelligence Agency. Forget the CIA's mystique. The courtroom is still connected to the secret world.

In criminal justice, identifications are notoriously bad. Cross-racial IDs are even worse. Think of the parallel to an intelligence agency that's fixed on a view about Iran's nuclear ambitions.

Sometimes in the criminal justice system, snitches or informants lie to the police and then lie under oath. They testify for reduced sentences, for money, or for other reasons. But not for truth. Think of the parallels to bounty hunters in Afghanistan, just after Sept. 11, who were rounding up Arabs who happened to be in the wrong place at the wrong time.

Sometimes in the criminal justice system, cops and prosecutors commit misconduct. Rather than let crimes go unsolved, they pin charges on somebody they assume is guilty — or they assume will commit future crimes. Think of the parallels to preemptive war.

Plus, in the criminal justice system, the threat of enhanced sentences and mandatory minimum sentences puts pressure on defendants, real pressure. Rather than let the process drag on, rather than roll the dice with a jury, these defendants sometimes plead to something they didn't do. They cut their losses. They make a rational calculation.

Face it. We can't do much about Guantanamo. Congress has frozen the president into an equation where he can't add or subtract detainees. But we can do something about criminal justice. Right now.

So the next time your mind wanders to Guantanamo, stop. Focus instead on an innocent person held in jail, not in Cuba but right here in the United States. For a change, give him a name and a face to go along with the black color of his skin.