Coleman legal strategy: find votes

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Fritz Knaak, one of Coleman's attorneys, said over the weekend the next stop for the Senate race is probably the courthouse.

"It's my assessment at this time that it's virtually certain that somebody is going to be filing an election contest," he said. "You always allow yourself some chance to reflect, but given the numbers I wouldn't see any reason why we wouldn't at this time."

Ultimately, it would be up to Coleman, not his lawyers, to keep fighting. But Washington University political scientist Steven Smith doubts Coleman would give up easily.

"Keep in mind that they've spent many, many months and tens of millions of dollars on this campaign," he said. "So, for them to extend by a few weeks and a few hundred thousand dollars in legal bills seems like a small price to pay. And there's lots of pressure on him. This is a vote that might actually make a difference in the Senate. So, I think there will be Republicans, not only in Minnesota but elsewhere, who would say, 'put up a good fight and see how it turns out.'"

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

And Franken's unofficial lead is tiny. It's less than one-one hundredth of a percent. In fact, it's about the same size as the lead Coleman had going into the recount. But that doesn't mean it would be easy to overcome.

Once the canvassing board finishes its work, the losing candidate would have seven days to file an election contest. That's a special type of legal proceeding set out in Minnesota state law.

Minneapolis attorney Brian Rice has represented several legislative candidates in election contests.

"What all these election contest cases revolve around is one thing, and that's who's entitled to the piece of paper," he said.

The piece of paper, that is, certifying the winner. The candidate who's behind has to prove the election was decided in error. Over the course of the recount, at least three issues arose that could form the basis for an election challenge.

First there was the case of the missing ballots. During the recount, one precinct in Minneapolis came up 133 ballots short of the number counted on election night.

Elections officials searched a Northeast Minneapolis warehouse for more than five hours, but never found the ballots. In spite of objections from the Coleman campaign, the canvassing board used the election night tally for that precinct. If they hadn't done that Franken would have lost a net 46 votes. Expect to see that issue revisited, if there's an election contest.

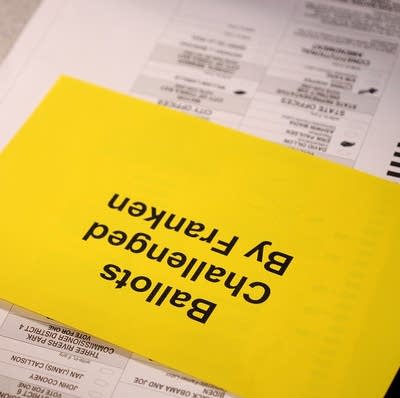

Then there's the issue of duplicate ballots. This one also focuses mostly on the DFL stronghold of Minneapolis. In several precincts, the Coleman campaign suspects some ballots were inadvertently counted twice. Coleman argues that led to a net gain of 110 votes for Franken.

But 110 plus 46 is 156. And on Saturday, Franken attorney Marc Elias pointed out that's still less than Franken's unofficial lead.

"The margin at 225 votes is fairly clear," he said. "I don't believe that if you added up the various issues that have been brought before us by the Coleman campaign in the last few days it exceeds 225 votes."

The Coleman campaign argues it has more votes out there, though. It says there some 650 erroneously rejected absentee ballots that haven't been counted yet. If Coleman still has a chance of winning, it may be in that pile of ballots.

But local elections officials say they've already reviewed all their rejected absentee ballots, and the ones they and both campaigns agreed should be counted already have been. The Minnesota Supreme Court is currently considering the matter.

So you have the missing ballots, the duplicate ballots and the additional rejected absentee ballots. But Ohio State University law professor Edward Foley said other issues could emerge in an election contest, from both campaigns.

"It is possible that Minnesota, believe it or not, hasn't see everything yet," he said. "A contest could surface things that just were not part of the recount."

If Coleman does initiate an election contest, the proceeding would get underway quickly. State law says the Minnesota Supreme Court Chief Justice would appoint a three-judge panel to hear the contest, and that hearings would begin before the end of the month.

But there's no telling when the contest would be settled. The election contest in Minnesota's 1962 gubernatorial race dragged on until March. And it might have gone longer if the the losing candidate hadn't waived his right to an appeal.