Central corridor light rail project has $200 million problem

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Metropolitan Council Chairman Peter Bell has what he calls a $200 million problem. That's the amount Bell says needs to be trimmed from the project to improve its chances of federal funding.

The Federal Transit Administration, which he hopes will finance up to one-half of the Central Corridor, is telling him the Met Council has low-balled the cost estimate. Right now the Met Council's projected price of the current design is about $930 million.

"The FTA has strongly suggested that we increase the (estimated) cost of that to over $1 billion," Bell says.

The feds say the Met Council has underestimated, among other costs, the effects of inflation. Bell says the diet needs to bring the cost closer to $835 million, to keep it in the running for federal funds.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

He says the diet is aimed at achieving what federal officials call the cost effectiveness index. The math for figuring the number is the line's projected number of riders and the time they save using light rail, divided by the cost of the project.

The cost effectiveness number is how the Federal Transit Administration ranks projects for federal funding. Bell says it would be good if the Central Corridor number were $23 or even $22 per rider, instead of the current calculation of $25.

He says that puts the project at a disadvantage compared to other proposals from around the country.

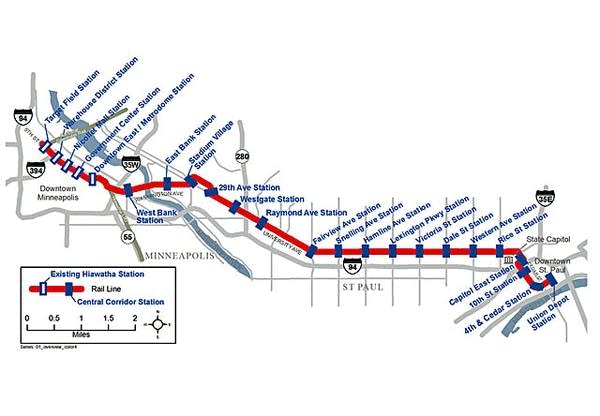

Met Council planners are looking at nearly every aspect of the 11-mile long line to trim costs, including not completing the last stretch to the Union Depot in St. Paul, and foregoing a tunnel under the U of M campus.

"Are they (the FTA) going to fund a project in St. Paul, or in Utah, or Texas, or Phoenix or Seattle? They use this as way to determine where they can get the best bang for the federal dollar," he says.

Bell says Met Council planners are looking at nearly every aspect of the 11-mile long line to trim costs. For example this week the council rejected an expensive add-on, a proposal for a downtown loop in St. Paul.

The pricetag can also be reduced by trimming the amount of underground utility work done when the rails are laid, by not building the line all the way to the Union Depot in downtown St. Paul, or by not building a $155 million tunnel underneath the University of Minnesota in Minneapolis.

The diet process is complicated because there are lots of voices with contending views at the table. The University of Minnesota, for example, wants to preserve the tunnel.

Peter Bell is counting on state and local money to finance the other half of the Central Corridor's cost. The goal is to have $280 million of the local and state funds nailed down by the end of the next legislative session.

"We're (planning) about half of that, or about $140 million, would come from state general obligation bonds. And the other half possibly, though a final determination hasn't been made, would come from the Met Council," he said.

The Met Council share, Bell says, would come from the motor vehicle sales tax revenues (MVST). Last fall Minnesotan's overwhelmingly approved spending all of MVST revenue on state transportation, including transit projects.

How do rural lawmakers feel about funding another Twin Cities light rail line when their constituents are clamoring for money to repair outstate roads and bridges?

Sen. Keith Langseth, DFL-Glyndon, in northwestern Minnesota, chairs the powerful Senate Capitol Investment committee which hears bonding requests. His committee will likely vote later this session on a $40 million bonding down payment on Central Corridor. Langseth says a number of outstate lawmakers support the rail line, based on their experience with the Hiawatha light rail line from Minneapolis to Bloomington.

"Many of the rural people have ridden on the Hiawatha train, and that one came in with about double the ridership that was expected instead of only half of what was expected by some of the critics of it. So I think people have gotten a little bit interested in rail as part of the congestion problem here in the Twin Cities," Langseth says.

The official name for the Central Corridor's diet plan is called preliminary engineering. Winning Federal Transit Administration permission late last year to begin preliminary engineering is an important vote of confidence by the agency for the project.

Central Corridor is still as much as two years away from winning FTA permission for final design. Trimming the project's cost appears to be crucial to winning the permission and eventually completing the line by 2014.