Gasification may turn coal into 'clean' fuel

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Coal has a well-deserved bad reputation. Typical coal-burning power plants release mercury, sulfur, nitrogen oxides, and lots of carbon dioxide.

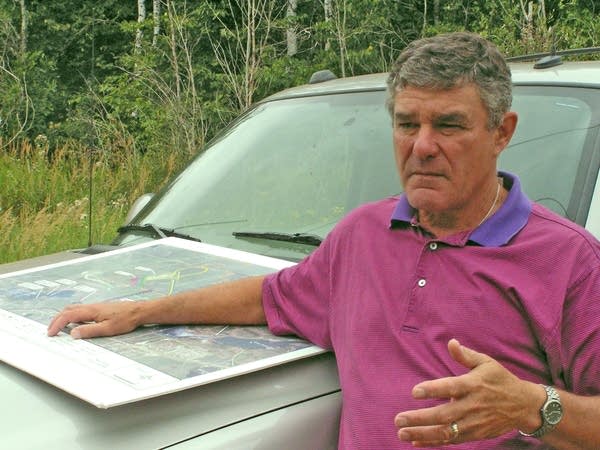

But Tom Micheletti says there's a way to use coal to generate power with very little pollution. That's what he's planning to do in the wild and green back country just off Highway 169 on the Iron Range.

CAN COAL BE A CLEAN FUEL?

Using heat, steam, pressure, and oxygen, coal can be broken down into a relatively clean gas, and a handful of other chemical byproducts. The gas is burned to turn generators and produce electricity. The technology is called Integrated Gasification Combined Cycle (IGCC). Micheletti says the technology isn't new, but applying it this way is.

Turn Up Your Support

MPR News helps you turn down the noise and build shared understanding. Turn up your support for this public resource and keep trusted journalism accessible to all.

"All we're doing is marrying the gasification technology with a technology that's been well-established, the combined cycle technology -- power plant technology," Micheletti says. "And all we're doing is simply putting those two technologies together."

Micheletti and his wife are former energy executives. Micheletti worked with Minnesota Power and Northern States Power Company while his wife, Julie Jorgensen, worked with NRG Energy and the Cogeneration Corporation of America. They formed Excelsior Energy Inc. to develop the Mesaba Energy Project, which would be the nation's first large-scale coal gasification electric power plant. At 600 megawatts, Mesaba Energy would dwarf demonstration plants now online in Indiana and Florida.

Micheletti says coal gasification is the only way to generate relatively clean electricity with a fuel that is readily available.

"It's the key to our energy future, to the extent that we need to use coal," Micheletti says. "And I think all experts who've studied our energy future indicate that at least half of our base-load plants must come from coal."

Why coal? It's the one fuel America has plenty of, from underground mines in the Appalachian states to huge coal fields in western states like Wyoming.

PLENTIFUL COAL SUPPLY IS KEY

Coal gasification is not only promising, experts say, it's more practical than other potential energy sources. Nuclear energy creates dangerous radioactive waste. Natural gas is becoming more scarce and more expensive. Biomass, solar, and wind are appealing, but not ready to provide the amount of energy this nation needs.

"We have a lot of coal in the U.S.," Harvard University professor Daniel Schrag says. "We're very fortunate that way. The problem is that coal produces more carbon dioxide per unit of energy than any other fossil fuel. And so, when we burn coal and make electricity, it's really bad for the climate system."

Schrag heads the Harvard University Center for the Environment. And now, by necessity, he's become something of an expert on energy production.

"I am a climatologist," Schrag says. "I study the history of climate on all time scales in earth history, from millions of years ago to the last few decades."

"I think quite a bit about what climate change is likely to bring in the future, and what to do about climate change. And that means thinking hard about our energy supplies," he says.

Schrag has seen a huge increase in the amount of carbon dioxide in the last 300 years. He say there's more CO2 around us now than humans have ever experienced. Carbon dioxide is a greenhouse gas. It blankets the earth, forcing temperatures higher.

Schrag is convinced that coal gasification will have to be a major component in America's energy future, because gasification can trap CO2 and prevent it from entering the atmosphere.

Schrag says when used to generate electricity, coal gasification has big advantages over conventional power plants.

"You get more energy for the amount of coal you put in, and that's good for carbon emissions," says Schrag. "The other thing is that it seems to be cheaper in an IGCC plant, or a gasification plant, to capture the carbon dioxide after one extracts the energy from the coal, and then makes it much easier to capture it and inject it into a geological reservoir."

GETTING RID OF CARBON DIOXIDE

The key, Schrag says, is a process called sequestration. You capture, and then lock that carbon dioxide away, where it won't escape into the atmosphere.

Near oceans, carbon dioxide can be compressed and piped into sediment under deep water, where he says, it will liquify and stay put. Inland, sequestration can occur in underground oil wells or aquifers. It's already being done in a large industrial complex just outside the town of Beulah, North Dakota.

The Dakota Gasification Co. turns coal into a burnable gas and almost a dozen byproducts like liquid nitrogen and ammonia. It also produces plenty of carbon dioxide. But the CO2 is not vented into the air. It's trapped and compressed in a series of large and very noisy pumps.

Plant manager Fred Stern describes the process.

"This piping...is the final piping from the compression," Stern says. "At this point it goes underground, crosses underneath the roadway, (and) begins migrating off to the west-northwest. And that's the start of its 205-mile trip from here to Canada."

At the end of its trip in Saskatchewan, the carbon dioxide is pumped into oil wells. It helps push the last oil out of the wells, leaving the carbon gas trapped underground.

CAN IT WORK IN MINNESOTA?

And that's all very good in North Dakota, according to some Minnesotans. But they say this process doesn't do anything to support putting a gasification plant just anywhere, since northeast Minnesota has no oil wells and no deep oceans.

What the Iron Range has is a solid rock subsoil, with no room for carbon dioxide. Mesaba Energy's Tom Micheletti admits his plant would not immediately trap carbon dioxide. But he says it can, and most likely will. He says its possibe to pipe the CO2 to oil wells hundreds of miles away in the Dakotas.

It may be that coal is so cheap that even the extra cost of capturing the carbon and storing it underground may still make it cheaper than...wind and solar.

But others say even good power plants might be a bad idea. Ross Hammond, a 30-year veteran of the energy industry, retired from NRG Energy in 2003. Hammond is a board member of Fresh Energy, a Minnesota organization dedicated to clean and renewable energy.

Hammond says gasification's proponents are overlooking an even more valuable resource -- conservation.

"We start with conservation," Hammond says. "Then we find our ways to do things more efficiently and cleanly. And then we look at the sources. But first you look at the usage. If you can reduce your usage you don't need to build more power plants."

Before the nation turns to coal, Hammond says, it should first explore all opportunities for clean energy.

"When we've exhausted all the clean options - including biomass, and photovoltaics, and wind, and the other options - then we need to look at coal, because that's going to be a viable resource for the next several hundred years," Hammond says. "And we need to look at ways to burn it efficiently, and capture the global warming pollution."

ALTERNATIVES MAY COST TOO MUCH

But Harvard's Daniel Schrag says it's not as simple as pushing money toward pollution-free energy.

"The answer is complicated," says Schrag. "The answer is -- perhaps not. It may be that coal is so cheap that even the extra cost of capturing the carbon and storing it underground may still make it cheaper than the alternatives, than wind and solar. We have to decide that by doing some experiments on a large industrial scale, and figure out what the real costs area."

Schrag says eventually we'll need it all, including nuclear, hydro, wind and biomass. But to satisfy the nation's hunger for energy, he says we'll need coal -- which he says is best used in coal gasification.

The Mesaba Energy project could get a go-ahead within the next year. While it would be the first large gasification plant, it may not be the only one. Nationwide, there are as many as 50 additional coal gasification power projects on the drawing boards.