Scientists learn Great Lakes storms may be trending further north, warming faster due to climate change

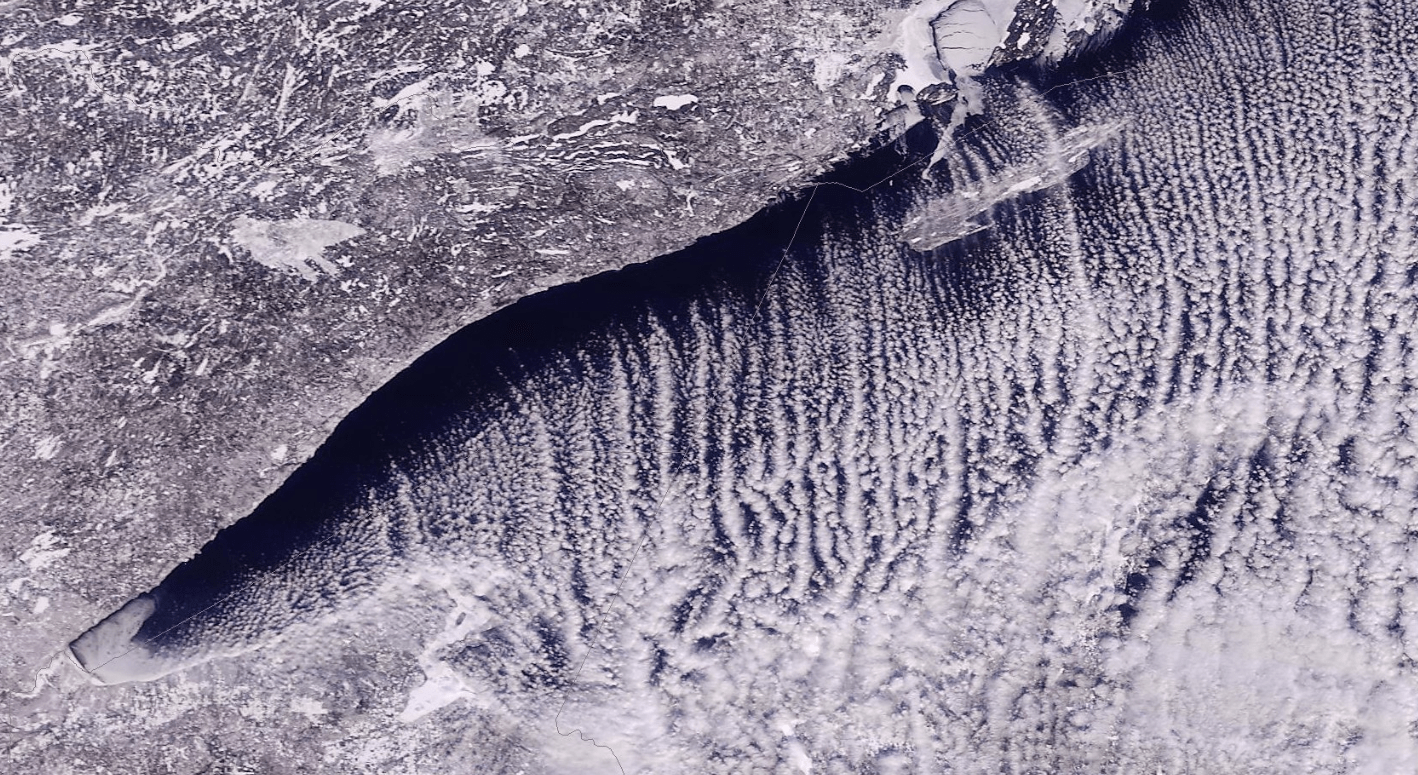

Lake-effect snow over Lake Superior on Feb. 13, 2020.

NASA via University of Wisconsin-Madison

Go Deeper.

Create an account or log in to save stories.

Like this?

Thanks for liking this story! We have added it to a list of your favorite stories.

Audio transcript

NINA MOINI: That's right. It can be pretty, as well. It's a winter wonderland for parts of the Great Lakes region that are digging out from a lake-effect snow storm that brought 6 feet of snow. And as we heard from Sven, the north shore will get their own dose of lake-effect snow today.

And there's new research trying to better predict what winter storms will look like in the Great Lakes, which stretches from Minnesota to Upstate New York. So joining me now to explain is one of the authors of this study, Abby Hutson. Abby is a researcher at the Cooperative Institute for Great Lakes Research at the University of Michigan. And she's on the line. Welcome to Minnesota Now, Abby.

ABBY HUTSON: Hi. Thanks for having me.

NINA MOINI: Well, you might have just heard us talking with one of our great meteorologists, Sven Sundgaard-- so much going on with the weather, so many trends to track. What got you interested in this research?

ABBY HUTSON: Well, I grew up in the Great Lakes region. And let me tell you, us in the Midwest here love to say, our weather is constantly changing. If you don't like the weather, stick around for a day. It's going to change.

And how the weather-- these big storm systems-- and how it impacts our Great Lakes region is really important. And so looking into these is extremely important for everything going around in the Great Lakes region.

NINA MOINI: Yeah. Let's start with the big picture. Broadly speaking, what did your research really conclude about winter weather in the Great Lakes?

ABBY HUTSON: Sure. Well, specifically, we were looking at these big storm systems. These big winter storms are the clippers that is going to impact Minnesota here in the near future. And we looked at historical trends.

And what we found were a couple of things. One, that these big storms-- the center of the system seems to be tracking north, meaning that, with time, we've seen these storms passing over to the more northern regions of the Great Lakes, as opposed to typically going more southern. And we're also seeing that these big, large storms, they're getting warmer with time. The trends have shown that the storms themselves and the air masses in the storms are warming at a rate faster than we would typically expect with our normal rate of climate change.

NINA MOINI: And so, what drives the unpredictability that you were talking about in the Great Lakes region?

ABBY HUTSON: Sure. What drives the unpredictability of these storms has a lot to do, really, with these patterns that are affecting the globe worldwide. We call them global teleconnections. And many of the audience have probably heard of the teleconnection, say, El Niño or La Niña.

NINA MOINI: Yeah.

ABBY HUTSON: And there's more than that one. But there's multiple ones. And they affect the larger, upper air systems that drive these large storms into or out of the Great Lakes region. And a lot of those teleconnections vary from year to year. And they can last from a month to five years at a time.

And those can impact our larger-scale storm storms and their tracks through the Great Lakes. Say, for example you can typically get-- say, with an El Niño, you can get wetter, wetter winters or something along those lines. That has to do with these global teleconnections.

And it varies from year to year. And we see that very much so in the data. The number of storms from one year means nothing to predicting the number of storms the following year. And so that does lead to considerable uncertainty when you, say, want to do a seasonal forecast.

NINA MOINI: Yeah. I'm always like, is this climate change? Or is it just a fluke? Or what's going on-- when things go up and down, up and down. So you looked at decades of data. And tell me how that kind of helped to bolster the research.

ABBY HUTSON: Sure. Yeah. We were able to use data since 1960, since the cold season of 1960-- so technically, 1959. And that really did help us. We were able to create these yearly averages and do it in a way where we can look at the averages of all the storms that happened in one season all together.

And by doing these averages over a long time span with lots of samples, we're able to make very conclusive statistical statements about what these storms are doing. And that gives us the significance that we're looking for. So looking over since 1960, we are able to see definitively that these storms-- hey, the air masses in the storms are, in fact, warming with time at a rate faster than we expected. And they're also bringing more moisture than we expected. And it's very useful to have that much data that far back.

NINA MOINI: Totally. So are you talking about freezing rain storms. Or like, when you're saying warmer but more precip, it sounds like-- what are you envisioning?

ABBY HUTSON: Sure. Yeah. Again, this is cold season. And the cold season in Minnesota, it definitely comes with the snow and ice.

NINA MOINI: Yeah.

ABBY HUTSON: But yeah, when I say warmer, I guess, warmer than they were back in the 1970s. And then also, when we were talking earlier about how the storm tracks are moving northward, that does change what Minnesotans will typically expect in the wintertime. That can bring warmer temperatures so much in the winter season that we can see rain from these storm systems with the great swings. Often, though, in the winter, when you get rain, you'll get snow pretty soon after or those really, really cold temperatures. But the trends are showing us that the chances of mixed precipitation, ice, and rain are increasing for the Minnesota area.

NINA MOINI: So, what do you do, Abby, with your research? Where does it go? Who does it help?

ABBY HUTSON: Sure. Well, right now, we're just publishing it in our scientific journals. And that helps people future on. But the great thing about our organization here with the Cooperative Institute for Great Lakes Research-- we're housed at the University of Michigan. But we also work very closely with the Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory, which is a NOAA laboratory.

And they work a lot with seasonal prediction and working with stakeholders in the region-- so people like emergency managers, or decision makers, or people who will be needing our forecasts for anything having to do with the Great Lakes. We hope that our research about what storms will bring-- what they're trending to do and hopefully will tell us about in the future. We're hoping that helps them make those decisions, say, for infrastructure in terms of flooding risk. Or even just, there's climate and fisheries-- and what we should anticipate.

NINA MOINI: Yeah. Lots of people are planning for the future and need to take that into account. Before I let you go, Abby, I'm curious. So this was specific to the Great Lakes region. Are you looking into research or thinking about how it might impact a more broad area, larger global, maybe just patterns of weather?

ABBY HUTSON: Mm-hmm. Yeah. Mainly, we're focused on the Great Lakes region. But we are tying it in to those larger, global patterns that we've seen in the past-- or excuse me, that typically are associated with these storms. We're continuing this research. We find it really fascinating to see what these trends have shown.

We want to look at future projections. We want to look at how these storms can be predicted, say, seasonally with less uncertainty in it. We want to know what's driving the uncertainty and maybe even be able to predict that with these large global teleconnections. And also, we're taking it global. And then we also want to take it much more regional.

NINA MOINI: Oh, sure.

ABBY HUTSON: We're trying to take these large storms and figure out what their impacts are in very specific regions of the Great Lakes. And hopefully, future research will really give us a lot of insight into that.

NINA MOINI: Awesome. Thank you so much for coming on with us and sharing your important research, Abby.

ABBY HUTSON: Yeah. Thank you so much.

NINA MOINI: That was Abby Hudson, researcher with the Cooperative Institute for Great Lakes Research at the University of Michigan.

And there's new research trying to better predict what winter storms will look like in the Great Lakes, which stretches from Minnesota to Upstate New York. So joining me now to explain is one of the authors of this study, Abby Hutson. Abby is a researcher at the Cooperative Institute for Great Lakes Research at the University of Michigan. And she's on the line. Welcome to Minnesota Now, Abby.

ABBY HUTSON: Hi. Thanks for having me.

NINA MOINI: Well, you might have just heard us talking with one of our great meteorologists, Sven Sundgaard-- so much going on with the weather, so many trends to track. What got you interested in this research?

ABBY HUTSON: Well, I grew up in the Great Lakes region. And let me tell you, us in the Midwest here love to say, our weather is constantly changing. If you don't like the weather, stick around for a day. It's going to change.

And how the weather-- these big storm systems-- and how it impacts our Great Lakes region is really important. And so looking into these is extremely important for everything going around in the Great Lakes region.

NINA MOINI: Yeah. Let's start with the big picture. Broadly speaking, what did your research really conclude about winter weather in the Great Lakes?

ABBY HUTSON: Sure. Well, specifically, we were looking at these big storm systems. These big winter storms are the clippers that is going to impact Minnesota here in the near future. And we looked at historical trends.

And what we found were a couple of things. One, that these big storms-- the center of the system seems to be tracking north, meaning that, with time, we've seen these storms passing over to the more northern regions of the Great Lakes, as opposed to typically going more southern. And we're also seeing that these big, large storms, they're getting warmer with time. The trends have shown that the storms themselves and the air masses in the storms are warming at a rate faster than we would typically expect with our normal rate of climate change.

NINA MOINI: And so, what drives the unpredictability that you were talking about in the Great Lakes region?

ABBY HUTSON: Sure. What drives the unpredictability of these storms has a lot to do, really, with these patterns that are affecting the globe worldwide. We call them global teleconnections. And many of the audience have probably heard of the teleconnection, say, El Niño or La Niña.

NINA MOINI: Yeah.

ABBY HUTSON: And there's more than that one. But there's multiple ones. And they affect the larger, upper air systems that drive these large storms into or out of the Great Lakes region. And a lot of those teleconnections vary from year to year. And they can last from a month to five years at a time.

And those can impact our larger-scale storm storms and their tracks through the Great Lakes. Say, for example you can typically get-- say, with an El Niño, you can get wetter, wetter winters or something along those lines. That has to do with these global teleconnections.

And it varies from year to year. And we see that very much so in the data. The number of storms from one year means nothing to predicting the number of storms the following year. And so that does lead to considerable uncertainty when you, say, want to do a seasonal forecast.

NINA MOINI: Yeah. I'm always like, is this climate change? Or is it just a fluke? Or what's going on-- when things go up and down, up and down. So you looked at decades of data. And tell me how that kind of helped to bolster the research.

ABBY HUTSON: Sure. Yeah. We were able to use data since 1960, since the cold season of 1960-- so technically, 1959. And that really did help us. We were able to create these yearly averages and do it in a way where we can look at the averages of all the storms that happened in one season all together.

And by doing these averages over a long time span with lots of samples, we're able to make very conclusive statistical statements about what these storms are doing. And that gives us the significance that we're looking for. So looking over since 1960, we are able to see definitively that these storms-- hey, the air masses in the storms are, in fact, warming with time at a rate faster than we expected. And they're also bringing more moisture than we expected. And it's very useful to have that much data that far back.

NINA MOINI: Totally. So are you talking about freezing rain storms. Or like, when you're saying warmer but more precip, it sounds like-- what are you envisioning?

ABBY HUTSON: Sure. Yeah. Again, this is cold season. And the cold season in Minnesota, it definitely comes with the snow and ice.

NINA MOINI: Yeah.

ABBY HUTSON: But yeah, when I say warmer, I guess, warmer than they were back in the 1970s. And then also, when we were talking earlier about how the storm tracks are moving northward, that does change what Minnesotans will typically expect in the wintertime. That can bring warmer temperatures so much in the winter season that we can see rain from these storm systems with the great swings. Often, though, in the winter, when you get rain, you'll get snow pretty soon after or those really, really cold temperatures. But the trends are showing us that the chances of mixed precipitation, ice, and rain are increasing for the Minnesota area.

NINA MOINI: So, what do you do, Abby, with your research? Where does it go? Who does it help?

ABBY HUTSON: Sure. Well, right now, we're just publishing it in our scientific journals. And that helps people future on. But the great thing about our organization here with the Cooperative Institute for Great Lakes Research-- we're housed at the University of Michigan. But we also work very closely with the Great Lakes Environmental Research Laboratory, which is a NOAA laboratory.

And they work a lot with seasonal prediction and working with stakeholders in the region-- so people like emergency managers, or decision makers, or people who will be needing our forecasts for anything having to do with the Great Lakes. We hope that our research about what storms will bring-- what they're trending to do and hopefully will tell us about in the future. We're hoping that helps them make those decisions, say, for infrastructure in terms of flooding risk. Or even just, there's climate and fisheries-- and what we should anticipate.

NINA MOINI: Yeah. Lots of people are planning for the future and need to take that into account. Before I let you go, Abby, I'm curious. So this was specific to the Great Lakes region. Are you looking into research or thinking about how it might impact a more broad area, larger global, maybe just patterns of weather?

ABBY HUTSON: Mm-hmm. Yeah. Mainly, we're focused on the Great Lakes region. But we are tying it in to those larger, global patterns that we've seen in the past-- or excuse me, that typically are associated with these storms. We're continuing this research. We find it really fascinating to see what these trends have shown.

We want to look at future projections. We want to look at how these storms can be predicted, say, seasonally with less uncertainty in it. We want to know what's driving the uncertainty and maybe even be able to predict that with these large global teleconnections. And also, we're taking it global. And then we also want to take it much more regional.

NINA MOINI: Oh, sure.

ABBY HUTSON: We're trying to take these large storms and figure out what their impacts are in very specific regions of the Great Lakes. And hopefully, future research will really give us a lot of insight into that.

NINA MOINI: Awesome. Thank you so much for coming on with us and sharing your important research, Abby.

ABBY HUTSON: Yeah. Thank you so much.

NINA MOINI: That was Abby Hudson, researcher with the Cooperative Institute for Great Lakes Research at the University of Michigan.

Download transcript (PDF)

Transcription services provided by 3Play Media.